The Forgotten Peace

|Chapter 2. Prelude to intervention

Texto completo

- 1 See the collection compiled by the Argentine diplomat Rómulo S. Naón (1914), a selection of which (...)

1The Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920 was the cataclysmic event in that nation’s modern history. Successive waves of rebellion transformed a corrupt and backward dictatorship, heavily dependent on foreign capital, into a modern, centralized state committed to a nationalist, populist pro g ram of economic development. Given the extensive foreign investment from the United States, Britain, Canada, and various European countries in Mexico’s railways, mines, and oilfields, and the many foreign nationals who came to Mexico to manage these investments, there was a strong international interest from the outset in the outcome of the Revolution. Aided by the telegraph, regular shipping connections and a network of resident “special correspondents,” newspapers across the United States and Canada provided constant coverage of the progress of the Revolution, focusing on political and military developments among the Mexican factions and dramatic stories about the fates of individual expatriates who became caught up in the conflict. Images of the major Mexican revolutionary figures became well-known to North American newspaper readers from frequent cartoons and caricatures. What seems a distant, foreign event to us today was daily news for the educated public of North America in 1914. For example, The Globe carried at least one story about Mexico and often several, most days of the week in the period between late April and early July 1914. The coverage of Mexico in leading American newspapers such as the New York Times was even more extensive.1

- 2 See, for example, the books written and edited by Wilson’s definitive modern biographer Arthur S. (...)

- 3 Wilson often had to explain to recipients of his personal notes that he had typed them himself. Fo (...)

2This story is populated by more than its fair share of memorable characters, but five in particular stand out. On the American side, the two principal actors were the standard bearers of the Democratic Party which had successfully recaptured the White House in a three-way race in the presidential election of 1912. The first was Woodrow Wilson, the only professional academic to become President of the United States, whose meteoric political career began when he left Princeton University to become Governor of New Jersey in 1910. Within two years he won the Democratic Party’s nomination and then the presidency, campaigning on a platform he called “ The New Freedom.” Wilson the moralist, the idealist, the reformer, the strict Presbyterian, is a figure whose name has become synonymous with an entire approach to the conduct of American foreign policy.2 At the time of this story, he was a newly elected President, whose greatest achievements and failures at the Paris Peace Conference lay five years in the future. He maintained a distant but vigilant presence at the Niagara Falls Peace Conference through the stream of detailed instructions, at times bordering on sermons, that he sent to the U.S. delegates. Wilson not only drafted these instructions but typed them himself, working late at night at the White House.3

- 4 For a brief sketch of Bryan as Wilson’s Secretary of State, see Link (1954), pp. 26–27. See also t (...)

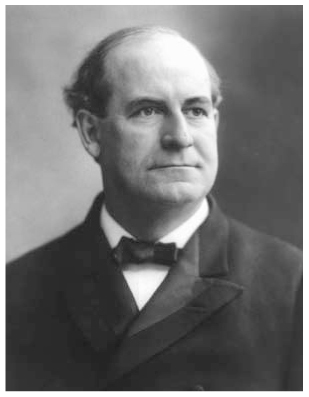

3Wilson’s intermediary in these proceedings was his Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, the great populist orator from Nebraska who had led the Democratic Party to crushing defeat in three previous presidential elections. Bryan was more familiar to the American public than Wilson since he had been a national political figure for twenty years and his garrulous personality made him a cartoonist’s dream.4

VENUSTIANO CARRANZA (1914). The original caption on this photograph read: “1914—Mexico City, Mexico—General Venustiano Carranza, who overthrew General Huerta, arriving in Mexico City.” Bettman BE071336

- 5 For brief character sketches of Villa and Carranza see Atkin (1969), pp. 51–52 and p. 131, respect (...)

4On the Mexican side, the two leading figures of the Constitutionalist forces whose cause Wilson and Bryan championed were Venustiano Carranza and Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Carranza was an aloof, taciturn, inflexible politician of urban middle-class origins and outlook. He had been Governor of his home state of Coahuila under the presidency of the apostle of the Revolution, Francisco Madero. After Madero’s death, Carranza rallied the disparate pro-Madero forces in northern Mexico around his Plan of Guadalupe, which designated him as the “First Chief of the Constitutionalist Army in charge of Executive Power.” Villa was the Constitutionalists’ most popular, reckless, and visible general. A passionate, cruel, mercurial figure from a humble peasant family, he was the quintessential rebel commander and Carranza’s opposite in every sense. Villa had assembled a fanatically loyal personal army in Chihuahua which became the Constitutionalists’ Division of the North. His early military victories in 1913 and the first half of 1914 had bolstered the Constitutionalists’ morale and convinced the Wilson Administration that the Constitutionalist side would inevitably prevail.5

VICTORIANO HUERTA, flanked by José C. Delgado (l.) and Abraham F. Ratner (between 1906 and 1916). Library of Congress LC-USZ62-97991

- 6 For two detailed and somewhat differing accounts of this sequence of events, known in Mexican hist (...)

- 7 See Atkin (1969), pp. 86–87 and 141; also Katz (1981), pp. 119–120.

- 8 Von Hintze quoted in Katz (1981), p. 120.

5The target of Wilson’s antipathy and the Constitutionalists’ mortal enemy was “the usurper” in Mexico City, General Victoriano Huerta. A professional soldier in the Federal Army, Huerta had been called out of retirement in February 1913 to help in defeating a mutiny against the government of President Madero. Instead of putting down the mutiny, Huerta cut a deal with one of its leaders, deposed Madero, and had himself appointed President. Madero was assassinated a few days later and, although Huerta denied responsibility for Madero’s murder, he was depicted ever afterwards by his many enemies as a man with blood on his hands.6 Huerta was an alcoholic who reportedly consumed a bottle of cognac a day. His management methods as President were eccentric: he was rarely found in his office, preferring to hold cabinet meetings in taverns or bars in the small hours of the morning, and he liked to do his “office work” in a car while driving around Chapultepec Park.7 Huerta’s methods for dealing with potential rivals and maintaining public order went well beyond exercising a “firm hand.” As Paul von Hintze, the German Minister in Mexico City, commented to Berlin: “the methods of the government correspond roughly to those employed in Venice in the early Middle Ages, and we could look upon them with equanimity were they not occasionally extended to foreigners.”8

- 9 Link (1956), pp. 278–79.

6The unfolding chaos of the Mexican Revolution confronted Woodrow Wilson with the first sustained test of the application of his populist, democratic ideals to foreign policy. One of the many ironies of Wilson’s presidency is that he entered office with virtually no experience of foreign affairs, nor even much interest in them.9 Yet within his first week in office he had issued a sweeping statement that the United States had “nothing to seek in Central and South America except the lasting interests of the peoples of the two continents.” Wilson declared:

- 10 Wilson Papers, Ser. 3, 2:20, March 12, 1913, quoted in Haley (1970), pp. 82–83.

We hold... that just governments rest always on the consent of the governed, and there can be no freedom without order based on law and upon the public conscience and approval. We shall lend our influence of every kind to the realization of these principles in fact and in practice.10

- 11 Link (1956), pp. 348–50.

- 12 Grieb (1969), p. 43.

- 13 Grieb (1969), p. 72.

7The first question that required Wilson to put these noble sentiments into practice was whether to recognize the regime of General Victoriano Huerta as the de facto government of Mexico. Wilson was shocked by the brutal murder of Madero, the first democratically elected President of Mexico in forty years. He baulked at the recommendation that landed on his desk from the State Department that the United States follow past American and European practice, and recognize Huerta as the de facto President.11 In his mind, recognition constituted approval, which he was not prepared to grant to Huerta.12 Accordingly, while most of the other countries with diplomatic missions in Mexico City proceeded to recognize Huerta, the United States did not, despite the fact that the United States was the only nation to have a full Ambassador in Mexico City. This reluctance on Wilson’s part constituted a break with the United States’ historic practice as a nation founded through revolution of extending de facto recognition to all governments in power, as the State Department carefully explained in a memorandum to Wilson.13

- 14 Grieb (1969), pp. 75–78.

8Over the first few months of his presidency, Wilson’s discomfort turned to deep mistrust of the advice he was receiving from many of his officials. He learned that Henry Lane Wilson, then the U.S. Ambassador in Mexico, had not only advocated the overthrow of Madero but had even facilitated the power-sharing arrangement negotiated inside the U. S. Embassy between Huerta and his chief rival, General Felix Diaz. As Ambassador Wilson bombarded Washington with telegrams arguing the necessity of recognizing Huerta, President Wilson’s reservations hardened into a determination that the United States could not countenance recognition of a regime established by the overthrow of a democratically elected leader.14 Huerta had to go.

- 15 Meyer (1972), p. 179. Meyer provides a very informative chapter, “Financing a Regime,” which situa (...)

- 16 Grieb (1969), p. 88.

- 17 Link (1956), pp. 354–55.

9The question then became how to remove Huerta. Withholding diplomatic recognition was the first step. This turned out to have significant economic repercussions for Huerta, as American and European bankers were reluctant to underwrite new loans to his regime in the absence of diplomatic recognition by its most powerful neighbour.15 Recall of Ambassador Wilson was the second step, even though this created the awkward situation that no replacement could be sent without extending de facto recognition to Huerta. Instead, the First Secretary, Nelson O’Shaughnessy, was appointed Chargé d’Affaires and tasked with confining his contacts to the Minister of Foreign Relations,16 although in fact he met Huerta frequently in the subsequent months. The third step was to send a trusted confidante, Wilson’s campaign biographer William Bayard Hale, to Mexico City to report directly to the President on conditions in the country. Hale spent two months in this mission and met a limited circle of American expatriates in the capital. Not surprisingly, he reported back to Wilson that Huerta enjoyed little popular support. Hale recommended that the United States take firm diplomatic action to force Huerta’s resignation and the replacement of his regime by a democratically elected government.17

- 18 Link (1956), pp. 356–60. Huerta went through six different Foreign Ministers in his sixteen months (...)

- 19 Link (1956), p. 361.

10This paved the way for Wilson’s next initiative: sending a personal representative to Mexico. For this task Woodrow Wilson selected a trusted friend, John Lind, a former Governor of Minnesota who had no knowledge of Mexico, Spanish or diplomacy. Lind was dispatched with a proposal to “mediate” the impasse between the two governments: the United States would offer recognition of a new Mexican government, if Huerta resigned and an interim government held free elections. Huerta’s Foreign Minister dismissed this mediation proposal out of hand.18 Lind withdrew to Veracruz where he was kept on for months, much against his will, to “report on developments.” Wilson briefed both Houses of Congress on the rebuff of Lind’s mission and concluded that, since the United States could not force its good offices on Mexico, the best it could do would be to adopt a policy of strict neutrality, maintain the existing arms embargo against Mexico, and watch patiently for the internal conflict between Huerta and his enemies to resolve itself. This policy was immediately dubbed “watchful waiting” by the American press. Despite the subsequent evolution of Wilson’s approach away from this passive stance towards a more proactive policy to undermine Huerta, the label stuck in the popular imagination (as evidenced in newspaper cartoons, and even a humorous song, produced during the Niagara Falls Peace Conference nine months later).19

11Up until this point, Wilson and Bryan had paid little attention to the Constitutionalists’ growing insurgency in northern Mexico. This loose coalition of former supporters of Madero, led by “First Chief ” Venustiano Carranza, refused from the start to recognize Huerta’s assumption of power. Wilson and Bryan started to pay more attention to their potential, encouraged by reporting from various U.S. consuls in northern Mexico, notably Thomas Carothers in Torreon who became an outright partisan of Pancho Villa. They were also lobbied by Lind, who argued that the United States had to find a domestic alternative to Huerta. By the autumn of 1913 Bryan and Wilson had come to the conclusion that the only force capable of realizing their goals for Mexico was the Constitutionalists.

12However, their first contact with Carranza and his cabinet was not auspicious. Wilson sent Hale to meet them in Nogales, Mexico, in mid-November with a proposal that the United States would permit them to buy arms in the United States if they supported Wilson’s plans to install a provisional government in Mexico City that would oversee new elections, and if they guaranteed the lives and properties of foreigners living in areas under their control. If such guarantees could not be provided by any party in Mexico, Wilson instructed Hale to warn that military intervention could follow. Carranza categorically rejected both the offers and the threats. Hale reported that the Constitutionalists “would be satisfied by nothing less than the destruction of Huerta and the old regime, and their unencumbered triumph.” Further:

- 20 Link (1956), pp. 382–84.

the Constitutionalists refused to admit the right of any nation on this continent acting alone or in conjunction with the European Powers to interfere with the affairs of the Mexican Republic... they held the idea of armed intervention as inconceivable and inadmissible on any grounds or upon any pretext.20

13Carranza broke off the negotiations with Hale, informing him that further communications should go through the Constitutionalists’ Minister of Foreign Affairs. Hale, bitter and rebuffed, returned to Washington.

14After these setbacks with both belligerent parties in Mexico, Wilson decided to issue a ringing statement clarifying the disinterested position of the United States and offering a sweeping defence of democratic government in Latin America. This position statement was drafted by Wilson and sent out by Bryan on November 24, 1913, to all American envoys in Europe, as a formal démarche to the other powers with an interest in Mexico. It is worth quoting in full:

- 21 United States Department of State (1922), pp. 443–34, File No. 812.00/11443d. Link (1956), p. 386, (...)

Our purposes in Mexico

The purpose of the United States is solely and singly to secure peace and order in Central America by seeing to it that the processes of self-government there are not interrupted or set aside.

Usurpations like that of General Huerta menace the peace and development of America as nothing else could. They not only render the development of ordered self-government impossible; they also tend to set law entirely aside, to put the lives and fortunes of citizens and foreigners alike in constant jeopardy, to invalidate contracts and concessions in any way the usurper may devise for his own profit, and to impair both the national credit and all the foundations of business, domestic or foreign.

It is the purpose of the United States, therefore, to discredit and defeat such usurpations whenever they might occur. The present policy of the Government of the United States is to isolate General Huerta entirely; to cut him off from foreign sympathy and aid, and from domestic credit, whether moral or material; and to force him out.

It hopes and believes that isolation will accomplish this end, and shall await the results without irritation or impatience. If General Huerta does not retire by force of circumstances, it will become the duty of the United States to use less peaceful means to put him out. It will give other Governments notice in advance of each affirmative or aggressive step it has in contemplation, should it unhappily become necessary to move actively against the usurper; but no such step seems immediately necessary.

Its fixed resolve is that no such interruptions of civil order shall be tolerated in so far as it is concerned. Each conspicuous instance in which usurpations of this kind are prevented will render their recurrence less, and in the end a state of affairs will be secured in Mexico and elsewhere upon this continent which will assure the peace of America and the untrammelled development of its economic and social relations with the rest of the world.

Beyond this fixed purpose the Government of the United States will not go. It will not permit itself to seek any special or exclusive advantages in Mexico or elsewhere for its own citizens, but will seek, here as elsewhere, to show itself the consistent champion of the open door. In the meantime, it is making every effort that the circumstances permit to safeguard foreign lives and property in Mexico, and is making the lives and fortunes of the subjects of other Governments as much its concern as the lives and fortunes of its own citizens.21

- 22 Grieb (1969), p. 71.

15The U.S. attempt to use such démarches to reduce international support for Huerta met with limited success. Despite U.S. opposition, by June 1913 all other countries with missions in Mexico City had decided to recognize Huerta’s regime as the de facto government of Mexico, save for Cuba, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. Only the latter three South American democracies agreed to follow the lead of the United States in their policies towards Huerta.22 The European powers maintained business as usual.

- 23 Tuchman (1958), Chapters 2 and 4, gives a fascinating account of American fears of Japanese strate (...)

- 24 Reports from Mexico City, Washington, London, and Tokyo between January 29 and February 3, 1914 do (...)

16Meanwhile, American observers suspected that Japan was exploiting the rupture in relations between the United States and Mexico to its political advantage.23 In 1913 Huerta made a purchase of arms from Japan, and in January 1914 a Japanese naval vessel on a good will visit to a Pacific port was received with great public enthusiasm and “unusual honours” by the Mexican government. The State Department watched this visit closely, suspecting that the Japanese were attempting to cultivate Mexico in order to put greater pressure on the United States to deal with the then vexing question of the discriminatory laws against Japanese immigrants recently passed in California. Reports circulated in the American press that Huerta and the Japanese government had signed a secret treaty to open western Mexico to new colonies of Japanese migrants, to be financed by British commercial interests, which in turn would pave the way for a Japanese base at Magdalena Bay on the Pacific Coast of Baja California. The Japanese Prime Minister reportedly declared that both the “Mexican hope and American suspicion that Japan will assist Mexico” were “wholly unfounded,” and that Japan was far too involved in disturbances in China to worry about affairs in distant Mexico. But the facts of the arms sale and the naval visit remained.24

- 25 Grieb (1969), pp. 129–30.

- 26 Link (1956), p. 366.

17British policy came under even closer scrutiny from Wilson, Bryan, and the U.S. Ambassador in London, Walter Page, as Britain was second only to the United States in importance as a source of foreign investment in Mexico. One British industrialist, Lord Cowdray, was the largest single investor in Mexico’s rapidly expanding oil industry, then based around the Gulf port of Tampico. The Royal Navy had a strong interest in the stability of Mexican oil production, having switched in 1912 to an all oil-powered fleet, and had deployed a powerful West Indies cruiser squadron to guard the approaches to Tampico. In a particularly ill-timed move which enraged Wilson, Sir Lionel Carden, the new British Minister to Mexico, arrived in the autumn of 1913 and presented his credentials to Huerta the day after the arrest of the Mexican Congress.25 Carden became a lightning rod for American suspicions, as he had made his name over a thirty-year career through his efforts to assert British economic interests in Latin America in the face of steadily growing American power. Walter Page, the U.S. Ambassador to London, dismissed Carden, foolishly, as a “slow-minded, unimaginative, commercial Briton, with as much nimbleness as an elephant.”26

- 27 Link (1956), pp. 369–77, gives a concise account of Anglo- American relations over Mexico, and Gri (...)

18Throughout 1913 the United States put increasing diplomatic pressure on Britain to distance itself from Mexico. Presented with the choice between good relations with a precarious regime in Mexico and good relations with a determined Administration in Washington, Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, opted for the latter. He sent his private secretary as a special envoy to meet Wilson and iron out hard feelings after the credentials incident. The British Government also distanced itself from Lord Cowdray, reduced the profile of its naval presence in the Gulf of Mexico, and put Sir Lionel Carden on a short leash. Britain signalled clearly to the U.S. Government that it would take no measures to protect Huerta, provided that the United States alerted Britain about any measures it planned to take that could affect the security of British interests in Mexico. By the beginning of 1914 much of Britain’s diplomacy towards Mexico was being channelled through its Ambassador in Washington, Sir Cecil Spring-Rice.27

- 28 Link (1954), p. 121.

19After two months of stalemate, Wilson and Bryan were ready to try a new, indirect approach to engaging the Constitutionalists. Their agent in Washington, Luis Cabrera, had provided fresh assurances to the State Department that the Constitutionalists would respect foreign property rights, including “just and equitable concessions.”28 More importantly, Wilson had come to the conclusion that a permanent solution to Mexico’s instability would require more than just the departure of Huerta and fresh elections. It would also require a new regime committed to land reform. Of the parties available to replace Huerta, only the Constitutionalists were committed to such a program.

20Wilson’s chosen instrument for facilitating a Constitutionalist victory was to lift the U.S. arms embargo against Mexico, which had been in place since March 1912. Although lifting the embargo would enable both sides in Mexico to rearm with U.S. weapons and munitions, Wilson knew that this measure would be of greater benefit to the Constitutionalists, given the long stretch of the U.S.–Mexico border under their control. Bryan spelled out the implications of this policy shift, in stark terms, in a message sent to all U.S. diplomatic missions on January 31, 1914:

- 29 Secretary of State to all diplomatic missions of the United States, Washington DC, January 31, 191 (...)

...the United States has received information which convinces it that there is a more hopeful prospect of peace, of the security of property, and of the early payment of foreign obligations if Mexico is left to the forces reckoning with one another than there would be if anything by way of a mere change of personnel were effected at Mexico [City]... Settlement by civil war carried to its bitter conclusion is a terrible thing, but it must come now, whether we wish it or not, unless some outside power is to sweep Mexico with its armed forces from end to end; which would be the beginning of a still more difficult problem.29

21The logic behind this message was explained in fuller terms by Wilson himself at a meeting in early February with the British Ambassador in Washington. Spring-Rice described the President’s thinking in a long telegram to Sir Edward Grey:

- 30 Spring-Rice to Grey, Washington, February 7, 1914. F.O. 115/1789 (British spelling and punctuation (...)

He [Wilson] said that, after long and serious consideration of the whole subject, and after consulting all sorts and conditions of men who had experience of the country, he had come to the conclusion that the real cause of the trouble in Mexico was not political but economic. The real cause was in fact the land question. So long as the present system under which whole provinces were owned by one man continued to exist, so long there would be perpetual trouble in the political world. Having arrived at the conclusion he [had] been obliged to alter the policy which at first he had pursued. He had at first hoped that it would be possible, although Huerta himself could not be recognised, for reasons of which I was fully aware, to find some person or persons who could form a provisional government under which elections could be held and a new President legally chosen. But it soon appeared that there was no one in Mexico today who could give adequate representation to the crying wants of those classes of population who were not so fortunate as to own land. A Government formed in Mexico City must of necessity [be] a government representing the interests of landowners. It could not be a government which could safely be trusted to solve that great question [which] was the prime cause of all political difficulties. It could not possibly be a government which the people could trust. But if that were impossible there remained another alternative, namely, a government upheld by a foreign power as a consequence of successful intervention. But successful intervention would unite against the invading party all the patriotism and all the energies of which the Mexicans were capable. To put such a government in power would be to substitute for a government which people could not trust a government which they perforce must hate.

Under such circumstances his thoughts had turned to the so-called “Constitutionalists.” They had many faults but they at least had one virtue. They did more or less adequately represent the crying needs of the agricultural population. This was especially true of Villa, who was a sort of Robin Hood and had spent a not uneventful life in robbing the rich to give to the poor. He had even at one time kept a butcher’s shop for the purpose of distributing to the poor the proceeds of his innumerable cattle raids. He had another great virtue. That was that he was quite aware of his deficiencies as a political organiser. He knew he could fight, but he knew also that he could not govern. Villa was the sword of the revolution and it was possible that someone would be found who would manage the political affairs of the revolution, when accomplished, under capable and disinterested advice.

Such were the reasons that had led the President to believe that Mexico had best be left to find her own salvation in a fight to the finish. He did not intend to interfere himself and he hoped that other Powers would not interfere. If no interference took place he believed that Huerta would fall sooner or later and a new government be formed which could better express the will of the people, and lead in the end to a peaceful and permanent settlement.30

- 31 See Grieb (1969), pp. 121–22, regarding arms sales to the Constitutionalists. The British Military (...)

22Wilson notified Congress that he was revoking the arms embargo against Mexico on February 3, 1914. Merchants along the border between Texas and Mexico moved swiftly to supply the Constitutionalist forces with rifles and ammunition. Stockpiles of munitions previously impounded by the U.S. Government under the embargo were released for sale to the Constitutionalists, despite the widespread apprehension among U.S. military officers that, sooner or later, U.S. troops would find themselves in Mexico fighting various Mexican forces armed with these new weapons.31 By early April the Constitutionalist forces were gaining ground in their fight against the Federal Army. Villa won a major victory by recapturing the strategic railroad junction at Torreon, while other Constitutionalist forces to the east began besieging Tampico.

- 32 Spring-Rice to Grey, Washington DC, April 25, 1914, F.O. 115/1793.

23However, Villa was also running out of money. He had consistently financed his army through cattle raids and confiscation of property (hence the U.S. insistence, in previous exchanges with the Constitutionalists, on respect for foreign property rights). When Torreon fell, Villa seized large stocks of cotton held by Spanish, French, and British merchants, but the British owners thwarted his plans by obtaining an injunction that prevented him from selling the cotton in the United States.32

- 33 Link (1956), p. 392. Spring-Rice, in his telegram of April 25, 1914, reports the estimate that the (...)

24Meanwhile, the centre and south of the country and above all, the capital, remained firmly under the control of Huerta. He had finally succeeded in strengthening his own position by raising a major loan from the Catholic Church and the propertied classes in Mexico City, which was reportedly sufficient to fund his forces for another six months.33 With the lifting of the embargo, Huerta was now able to import new weapons by sea from the United States and he could readily purchase more from Europe or Japan.

- 34 Grieb (1969), p. 122. Link (1954), p. 120, quotes Colonel House’s diary regarding a conversation w (...)

25Lifting the embargo did not prove sufficient as an instrument to achieve U.S. aims: further measures would be required to topple Huerta. In late March, Lind sent a message recommending that the United States apply direct military pressure against ports in the Gulf of Mexico to cut off the Huerta regime’s customs revenues and its lines of supply. Despite his public protestations to the contrary, Wilson in fact had been considering a military intervention along these lines for several months.34

26On April 9, 1914, an incident occurred in Tampico that provided Wilson with the pretext for such a move. A troop of about twenty Marines from the U.S.S. Dolphin, the flagship of the U.S. fleet anchored at Tampico, came ashore in a whaleboat behind Mexican military lines to purchase gasoline and were arrested and detained for an hour by an overzealous troop of the Tamaulipas rural guard. As soon as General Ignacio Morelos Zaragoza, the Mexican Federal Army commander, learned of this incident, he immediately released the Marines and issued an apology to their captain and the U.S. Consul. However, Rear Admiral Mayo, the commander of the U.S. fleet at anchor off Tampico, was not satisfied with the apology and insisted that the Mexicans fire a twenty-one-gun salute to the U.S. flag as full restitution for this insult to the national honour. Zaragoza demurred, on the grounds that he did not have the authority to offer such a salute, and cabled Mexico City for instructions. Mayo, notifying Washington of what he had done, received the full backing of President Wilson.

- 35 Address of the President delivered at a Joint Session of the Houses of Congress, April 20, 1914, o (...)

27What ensued were ten days of increasingly tortuous negotiations between the two capitals, which came down to whether the United States would reciprocate the twenty-one-gun salute it was demanding from Mexico. The final U.S. ultimatum expired on April 19, after Wilson refused to have O’Shaughnessy sign a Mexican protocol committing the two sides to reciprocal salutes, on the grounds that this would amount to recognition of Huerta’s government. This diplomatic impasse appears to have been a deliberate contrivance by Wilson to mobilize Congressional support for a limited use of force. It succeeded. On April 20, Wilson addressed a Joint Session of Congress and asked “for your approval that I should use the armed forces of the United States in such ways and to such an extent as may be necessary to obtain from General Huerta and his adherents the fullest recognition of the rights and dignity of the United States.”35 The House of Representatives approved a resolution to this effect that evening by a vote of 323 to 29. That night, Wilson asked his Secretaries of War and the Navy to draw up comprehensive plans for a military intervention in Mexico, including a full-scale blockade of both Mexican coasts, occupation of Tampico and Veracruz, and the possible dispatch of an expeditionary force to Mexico City.

- 36 Grieb (1969), pp. 151–54, and Link (1956), pp. 399–400.

28In the early hours of the following morning, an urgent cable arrived in Washington from the U.S. Consul in Veracruz, reporting that two hundred machine guns and fifteen million rounds of ammunition destined for Huerta’s troops were due to be unloaded later that day from a German ship, the Ypiranga. Wilson immediately ordered that the ship be detained and that the customs house in Veracruz be occupied. A detachment of U.S. Marines on station off Veracruz proceeded to do so in the face of increasing fire from the 800 Mexican troops guarding the city. In short order, it became evident that the Marines would have to occupy the entire port to prevent the rifles from being unloaded. Reinforced by the main body of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, some 3,000 U.S. troops proceeded to rout the Mexican defenders and seized the city on the morning of April 22. Meanwhile, following stiff German protests, the United States realized that it could not hold the ship of neutral Germany and released the Ypiranga, which then sailed to another Gulf port and unloaded its cargo. Bills of lading found on board by U.S. troops showed that the arms had been purchased for Huerta’s army in New York and had been transhipped via Germany to disguise their origin.36

- 37 See Link (1956), p. 402, regarding Wilson’s reaction to the casualties.

- 38 Link (1956), p. 405.

- 39 See, for example, Carden’s report to Grey: “Although the American Admiral had promised to [British (...)

- 40 Link (1956), pp. 402–05. This claim was repeated by Bryan when reporting the text of the Senate re (...)

29Although Wilson had already ordered plans for an invasion, he was apparently unnerved by the reality of the eighty-eight American casualties incurred in the impromptu action at Veracruz.37 He was also surprised by the political reaction to the occupation. General Huerta received a major boost in public support for his resistance to U.S. intervention. Throughout Latin America, public opinion and press reaction harshly condemned this latest U.S. military intervention in the affairs of a Latin American state. Anti-American riots broke out or were suppressed by police in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, and Uruguay.38 American expatriates in Mexico feared for their security, and there was a rush of refugees across the U.S. border and to the ports of Tampico and Veracruz. The British Government was privately irritated, as this rash move contradicted Wilson’s previous commitment that the United States would not take military action in Mexico without prior warning. British subjects, including Canadians, working in Mexico also felt at risk as they anticipated that an enraged Mexican citizenry would not make much distinction among the nationalities of different English-speaking expatriates.39 The great majority of American press and political opinion, apart from Wilson’s most loyal supporters in the Hearst press, regarded the seizure of Veracruz as the start of an undeclared war and an excessive means of seeking redress for a specific indignity to American honour, which was how Wilson had presented the Mexican situation to Congress on April 20.40

- 41 The full text of Carranza’s statement is contained in the telegram from Special Agent Carothers to (...)

- 42 Gage to Spring-Rice, Washington, DC, May 1, 1914, F.O. 115/1795.

30Most seriously for Wilson’s political aims, Carranza equally rejected the assurances sent to him by Bryan that the President was not seeking to declare war on Mexico but merely seeking “redress of a specific indignity.” Carranza replied to Wilson via U.S. Special Agent Carothers that the criminal action of Huerta would never be sufficient to involve Mexico in a war against the United States, “[b]ut the invasion of our territory and the stay of your forces in the port of Veracruz, violating the rights that constitute our existence as a free and independent sovereign entity, may indeed drag us into an unequal war, with dignity, but which until today we have desired to avoid.”41 After receiving this communication, Wilson reimposed the arms embargo de facto, reportedly in direct response to the representations of his military commanders, who now had troops in the field in Mexico and anticipated hostilities from all quarters.42

- 43 O’Shaughnessy to Secretary of State, Vera Cruz, April 25, 1914, United States Department of State (...)

- 44 Grieb (1969), p. 155.

31The Mexican Government took the next step of severing the remaining channel of direct communication between Washington and Mexico City. On April 22 Huerta’s Foreign Minister, Lopez Portillo y Rojas, sent Chargé Nelson O’Shaughnessy a formal note characterizing the seizure of Veracruz as an act of surprise, which violated Mexico’s goodwill in allowing U.S. forces friendly access to the harbour and which gave no time for non-combatants to seek safety. The note declared: “This act was contrary to international usages. If these usages do not demand, as held by many states, a previous declaration of war, they impose at least the duty of not violating humane considerations or good faith by the people whom the country which they are in has received as friends.” It concluded by stating that President Huerta had seen fit to terminate O’Shaughnessy’s mission and returned his passports.43 O’Shaughnessy and his family left the next day for Veracruz in a specially guarded train provided by the Mexican Government, accompanied by Huerta’s son as a guaranty of their safety. The State Department reciprocated by instructing the Mexican Chargé, A. Algara Romero de Terreros, to leave Washington the same day. The departing O’Shaughnessy took the initiative to turn over U.S. interests to the British Embassy, much to the displeasure of Wilson, who cancelled this arrangement when he learned of it and instructed Bryan that U.S. interests be represented by another government that had refused to recognize Huerta.44 Brazil agreed to take on the role, while Spain agreed to do the same for Mexico in Washington.

32By April 24, both Wilson and Huerta found themselves in a precarious position. The occupation of Veracruz had failed to stop the shipment of arms to Huerta, mobilized Mexican public support around his regime, generated a refugee flow of U.S. citizens out of Mexico, dismayed international and domestic public opinion, and even earned the ire of the intended beneficiaries of the policy, the Constitutionalists. In the face of these political setbacks, Wilson was hesitant to push the United States’ military advantage. Huerta, on the other hand, had lost control of Mexico’s principal port and major source of customs revenue. He knew that he could not dislodge the United States from Veracruz by force, or survive for long against renewed Constitutionalist attacks from the north, without an American withdrawal. Both sides were thus disposed to cease hostilities and save face for the moment, if an acceptable formula were proposed to them.

Notas

1 See the collection compiled by the Argentine diplomat Rómulo S. Naón (1914), a selection of which is reproduced in Appendix I.

2 See, for example, the books written and edited by Wilson’s definitive modern biographer Arthur S. Link, and the account of the “Wilsonian” school of American foreign policy in Mead (2001).

3 Wilson often had to explain to recipients of his personal notes that he had typed them himself. For example, he began a short note to the British Ambassador in Washington, Sir Cecil Spring-Rice: “My Dear Ambassador, I long ago wore out my pen hand by much writing, and am obliged, therefore, to ask my friends to regard notes which, like this, are written by myself on my own typewriter as in fact autograph.” Wilson to Spring-Rice, Washington, March 21, 1914, United Kingdom Foreign Office Papers (otherwise abbreviated F.O. in these notes) 115/1791.

4 For a brief sketch of Bryan as Wilson’s Secretary of State, see Link (1954), pp. 26–27. See also the selection of cartoons from the Naón collection in Appendix I.

5 For brief character sketches of Villa and Carranza see Atkin (1969), pp. 51–52 and p. 131, respectively. For a contrast between the two, see Quirk (1962), pp. 156–57. For a more sociological account of each of their factions, see Katz (1981), pp. 125–52.

6 For two detailed and somewhat differing accounts of this sequence of events, known in Mexican history as the “Ten Tragic Days,” see Grieb (1969), pp. 12–29, and Meyer (1972), pp. 45–82.

7 See Atkin (1969), pp. 86–87 and 141; also Katz (1981), pp. 119–120.

8 Von Hintze quoted in Katz (1981), p. 120.

9 Link (1956), pp. 278–79.

10 Wilson Papers, Ser. 3, 2:20, March 12, 1913, quoted in Haley (1970), pp. 82–83.

11 Link (1956), pp. 348–50.

12 Grieb (1969), p. 43.

13 Grieb (1969), p. 72.

14 Grieb (1969), pp. 75–78.

15 Meyer (1972), p. 179. Meyer provides a very informative chapter, “Financing a Regime,” which situates this factor in the larger context of the serious internal and external financial pressures on Huerta’s government.

16 Grieb (1969), p. 88.

17 Link (1956), pp. 354–55.

18 Link (1956), pp. 356–60. Huerta went through six different Foreign Ministers in his sixteen months as President. To minimize confusion, I have omitted their names at most points.

19 Link (1956), p. 361.

20 Link (1956), pp. 382–84.

21 United States Department of State (1922), pp. 443–34, File No. 812.00/11443d. Link (1956), p. 386, attributes the drafting of the statement to Wilson himself.

22 Grieb (1969), p. 71.

23 Tuchman (1958), Chapters 2 and 4, gives a fascinating account of American fears of Japanese strategic designs in Mexico. According to Tuchman, many of the American press reports of Japanese plans to obtain a naval base in Mexico were the product of deliberate disinformation by German agents.

24 Reports from Mexico City, Washington, London, and Tokyo between January 29 and February 3, 1914 document these perceptions of Japanese activity in Mexico: see F.O. 115/1789. Also note a report by T. B. Hohler of the British Legation in Mexico City, March 11, 1914, concerning the U.S. Chargé’s perceptions of Japanese activities, F.O. 115/1791; and telegram 34 from the British Legation in Tokyo reporting the Japanese Prime Minister’s statement on the issue, April 27, 1914, F.O. 115/1794. For the story about the secret treaty between Japan and Mexico, see the Washington Herald, March 12, 1914. The Herald noted that two years previously the Taft Administration had felt required to invoke the Monroe Doctrine against Japan to counter a plan by Japan to obtain basing rights in Baja California.

25 Grieb (1969), pp. 129–30.

26 Link (1956), p. 366.

27 Link (1956), pp. 369–77, gives a concise account of Anglo- American relations over Mexico, and Grieb (1969), pp. 125–41, provides more detail, including an explanation of the naval dimension. See also Calvert (1968). Reading the messages exchanged between Sir Edward Grey and his respective Ambassadors in Washington and Mexico City, contained in the British Foreign Office files for the first half of 1914 (S 830, F.O. 115), reveals how much of Spring-Rice’s time was devoted to reporting on Mexico.

28 Link (1954), p. 121.

29 Secretary of State to all diplomatic missions of the United States, Washington DC, January 31, 1914, United States Department of State (1922), pp. 446-447, File No. 812.00/10735a.

30 Spring-Rice to Grey, Washington, February 7, 1914. F.O. 115/1789 (British spelling and punctuation preserved).

31 See Grieb (1969), pp. 121–22, regarding arms sales to the Constitutionalists. The British Military Attaché in Washington, Lieutenant Colonel Gage, reported the widespread opposition in “U.S. military circles” to the lifting of the embargo in his quarterly military report to Spring-Rice, May 1, 1914, F.O. 115/1795.

32 Spring-Rice to Grey, Washington DC, April 25, 1914, F.O. 115/1793.

33 Link (1956), p. 392. Spring-Rice, in his telegram of April 25, 1914, reports the estimate that the domestic loan had given Huerta funds to fight for another six months.

34 Grieb (1969), p. 122. Link (1954), p. 120, quotes Colonel House’s diary regarding a conversation with Wilson on October 30, 1913, in which Wilson envisaged a blockade of all Mexican ports as the first step in a direct U.S. military intervention in Mexico. Spring-Rice also recorded a private conversation with General Wood, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, in which Wood decried his inability to obtain any political direction or even access to political circles in the Wilson Administration. Foreseeing the need for such a plan, Wood had drawn one up anyway: it envisaged the complete occupation and pacification of Mexico. See Spring-Rice to Grey, Washington DC, January 23, 1914, F.O. 115/1789.

35 Address of the President delivered at a Joint Session of the Houses of Congress, April 20, 1914, on “The Situation in Our Dealings with General Victoriano Huerta at Mexico City,” 63rd Congress, 2nd Session, House Document No. 910, reprinted in United States Department of State (1922), pp. 474–76, File No. 812.00/11552. For the evolution of U.S. demands and Mexican counterdemands over the Tampico incident, see United States Department of State (1922), pp. 448–78.

36 Grieb (1969), pp. 151–54, and Link (1956), pp. 399–400.

37 See Link (1956), p. 402, regarding Wilson’s reaction to the casualties.

38 Link (1956), p. 405.

39 See, for example, Carden’s report to Grey: “Although the American Admiral had promised to [British] Admiral Craddock that no hostile step would be taken without sufficient notice to enable foreigners to embark, American Marines were landed at Vera Cruz this morning.” Mexico telegram no. 88, April 22, 1914, F.O. 115/1793. Carden and Admiral Craddock then spent the following week arranging for the evacuation of several thousand English-speaking expatriates, the majority of whom were Americans, via trains from Mexico City to Veracruz and ships from Tampico. These operations elicited personal expressions of gratitude for Carden’s work from his previous critics, Page, Bryan, and Wilson.

40 Link (1956), pp. 402–05. This claim was repeated by Bryan when reporting the text of the Senate resolution approved on April 22: “Please note the word ‘justified’ is used instead of ‘authorized.’ This was done to emphasize the fact that the resolution is not a declaration of war but contemplates only the specific redress of a specific indignity.” Secretary of State to certain U.S. Diplomatic Missions, Washington, April 22, 1914, in United States Department of State (1922), pp. 483–84, File No. 812.00/11637a.

41 The full text of Carranza’s statement is contained in the telegram from Special Agent Carothers to Secretary of State, El Paso, Texas, April 22, 1914, United States Department of State (1922), pp. 483–84, File No. 812.00/11618.

42 Gage to Spring-Rice, Washington, DC, May 1, 1914, F.O. 115/1795.

43 O’Shaughnessy to Secretary of State, Vera Cruz, April 25, 1914, United States Department of State (1922), p. 490, 123Os4/123.

44 Grieb (1969), p. 155.

Índice de ilustraciones

| |

|---|---|

| Leyenda | WOODROW WILSON (December 2, 1912). Library of Congress LC-USZ62-13028 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/uop/docannexe/image/203/img-1.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 77k |

| |

| Leyenda | WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN (c. 1908). Library of Congress LC-USZ6-831 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/uop/docannexe/image/203/img-2.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 62k |

| |

| Leyenda | VENUSTIANO CARRANZA (1914). The original caption on this photograph read: “1914—Mexico City, Mexico—General Venustiano Carranza, who overthrew General Huerta, arriving in Mexico City.” Bettman BE071336 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/uop/docannexe/image/203/img-3.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 132k |

| |

| Leyenda | Pancho VILLA (between 1908 and 1919). Library of Congress LC-DIG-npcc-19554 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/uop/docannexe/image/203/img-4.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 123k |

| |

| Leyenda | VICTORIANO HUERTA, flanked by José C. Delgado (l.) and Abraham F. Ratner (between 1906 and 1916). Library of Congress LC-USZ62-97991 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/uop/docannexe/image/203/img-5.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 111k |

| |

| Leyenda | MAP OF MEXICO AND THE MEXICAN STATE OF MORELOS (around 1910) |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/uop/docannexe/image/203/img-6.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 235k |

Salvo indicación contraria, el texto y otros elementos (ilustraciones, archivos adicionales importados) se puede utilizar bajo licencia OpenEdition Books License.