Roccagloriosa II

| ,Parte I. L’oppidum sul M. Capitenali

Capitolo 3. la documentazione di II e I secolo a.C.

Texto completo

1. Strutture abitative

- 1 Il tesoretto includeva 18 monete di argento ed una di bronzo provenienti da svariate zecche della M (...)

- 2 Si consideri, in particolare, il tesoretto monetale rinvenuto in una casa dell’abitato sul Montrone (...)

- 3 Nonostante un evidente scadimento del livello di vita nell’oppidum nel corso del III secolo, si tra (...)

- 4 Si consideri il piatto di ceramica campana, databile alla metà del II secolo a.C. rinvenuto nell’Ar (...)

11.1. I processi di trasformazione messi in moto dalle conquiste romane della prima metà del III secolo a.C. si manifestano anche nell’oppidum di Roccagloriosa, come ci indicano sia la cronologia delle tombe più recenti rinvenute nella necropoli La Scala sia l’evidenza della ceramica associata alle strutture abitative, che mostra un notevole calo nella seconda metà del III secolo a.C. È molto probabile che la forza di attrazione esercitata dai nuovi centri inseriti nel sistema di potere politico-militare di Roma, quale la colonia latina di Paestum, abbia avuto gran presa sulle élites lucane di Roccagloriosa (Torelli 1990, 330), che molto probabilmente vi si trasferiscono almeno in parte (Torelli, ibid.), a giudicare dalla cesura riscontrata nella necropoli in località La Scala dopo il primo quarto del III secolo a.C. Conseguenze simili, anche se di natura più circoscritta, si potrebbero essere verificate in altre realtà indigene locali, quale il sito di Caselle in Pittari/Laureili, un altro punto nodale del comprensorio di cui Roccagloriosa potrebbe aver rappresentato il centro ‘politico’ preminente, a giudicare dalla poderosa collocazione difensiva e la massiccia opera di fortificazione. Il tesoretto monetale di recente rinvenuto a Caselle in Pittari1 e datato nel primo quarto del III secolo a.C., come tanti altri nella Lucania interna2, sembrerebbe segnare un momento di trasformazione del sistema insediativo comprensoriale. I dati raccolti in questo capitolo sui materiali abitativi di II e I secolo dall’oppidum e parte dei materiali ceramici più tardi provenienti dalla ricognizione delle aree extra-murane (supra, cap. 1) indicano tuttavia, in maniera assai convincente, che quel processo di trasformazione non ha implicato un rapido ed immediato spopolamento dell’oppidum e del territorio circostante, come è stato altrove affermato sulla base dell’evidenza della sola necropoli. Essi documentano, piuttosto, un uso continuato di varie strutture a livelli ridotti3 nella seconda metà del III secolo e quindi utilizzo/frequentazione degli spazi occupati dall’oppidum quale suolo agricolo, con una popolazione stanziale assai limitata ed in qualche caso parziale riutilizzazione degli edifici precedenti, a partire dal II secolo a.C. L’evidenza ceramica al riguardo non lascia dubbi sulla esistenza di una attività di sfruttamento agricolo dell’area, probabilmente con presenza umana stanziale, nel corso dell’età tardo-repubblicana come già segnalato in varie occasioni4.

2Più di recente, nel contesto dell’analisi delle aree extra-murane, è stato altresì possibile identificare alcuni esempi di strutture abitative che appartengono senza dubbio a questa fase di abitazione tarda dell’oppidum.

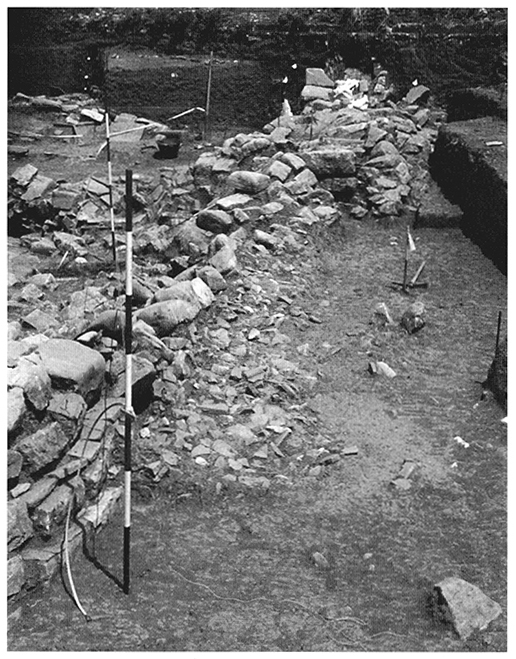

1.2. Il Pianoro Centrale

3La situazione geomorfologica assai precaria del Pianoro Centrale, con una serie di movimenti franosi verificatisi nel corso del III secolo, non ci consentono di estrapolare in maniera chiara ed univoca le probabili modifiche strutturali apportate dalla fase tarda di utilizzo di vari ambienti delle case signorili di IV secolo a.C. Ciò, purtroppo, a dispetto delle abbondanti tracce di attività relative al periodo in esame evidenziate dai materiali ceramici. La fornace nell’ambiente A5 del complesso A rappresenta senz’altro il punto di convergenza di tali attività, anche se come già discusso in maniera analitica in Roccagloriosa I (85-91) il suo periodo di attività è da riferirsi alla prima metà del III secolo. L’area di acciottolato rinvenuta immediatamente a sud della struttura, ad un livello leggermente superiore del piano di cottura e l’abbondante scarico di ceramica da cucina (che copre un arco cronologico abbastanza ampio), sono molto probabilmente da mettere in connessione con i più tardi muretti di terrazzamento (fig. 61) che delimitano uno spazio di uso abitativo databile fra la fine del III e la fine del II secolo, ed includono tracce di una frequentazione assai più tarda. Infine, un piano di livellamento in tegole e ciottoli, a copertura di un enorme scarico di materiali ceramici (fig. 62), è stato rinvenuto immediatamente ad est del grande muro perimetrale est del complesso (F 17), in relazione ad una assisa in grossi blocchi di calcare rozzamente squadrati che si sovrappone al muro più antico (vedi Roccagloriosa I, fig. 72) e, senza dubbio, costituisce un elemento della fase di terzo secolo avanzato adoperata fino al I sec. a.C. Tuttavia, come premesso, queste trasformazioni e rifacimenti di II secolo, che pure a giudicare dalla quantità di ceramica ad essi associabile, assicurano una sopravvivenza non insignificante di varie parti di questo nucleo abitativo, non ci permettono alcuna definizione, sia pur approssimativa, di un impianto planimetrico.

Fig. 61 - Pianoro Centrale: muretti di contenimento sul declivio immediatamente ad est del Complesso A.

Central Plateau: small terracing wall on the slope immediately to the east of Complex A.

Fig. 62 - Pianoro Centrale: scarico lungo il lato esterno (est) del muro posteriore del portico.

Central Plateau: dump along the exterior (eastern) side of the back Wall of the portico.

4Nel caso dell’adiacente complesso B, abbiamo invece un’evidente sovrapposizione di un lungo muro in blocchi di calcare (F 185), anche in questo caso molto probabilmente con funzione di terrazzamento, sui resti del muro in argilla cruda della fase di IV secolo (fig. 63-64). È una ulterirore prova del livello di riutilizzo di alcune delle aree abitative del Pianoro Centrale senza, tuttavia, permetterci di delinearne l’impianto o di valutarne l’estensione. A questa stessa attività di riutilizzo (nonostante l’evidenza assai meno probante) potrebbe appartenere il muro (o muri??) in grossi blocchi (forse riutilizzati dalla cinta muraria caduta in disuso) che rinforza i lati dell’ambiente B6.

Fig. 63 - Pianoro Centrale: muretto tardo (F 185) sovrapposto alle strutture di IV secolo a.C. (muro in mattoni crudi/argilla su zoccolo di calcare F 205) del Complesso B (da nord-ovest).

Central Plateau: later wall (F 185) put on top of the 4th c. B.C. structures (wall in unbaked clay on a lime-stone socle F 205) in Complex B (from the northwest).

5Ugualmente attribuibile allo stato franoso del terreno è l’impossibilità di fornire una pianta specifica di uno o due ambienti dell’Area PC86, ca. 50 m. a sud dei complessi A, B, C, dove le tracce di rifacimenti tardi rilevate dallo scavo sono abbondanti.

1.3. Il pianoro sud-est (fig. 65)

6La documentazione per una fase abitativa successiva alla devitalizzazione dell’oppidum, ancorché assai limitata e quasi del tutto priva di materiali ceramici associati, dato rinterro minimo esistente, ha restituito sul pianoro sud-est un ambiente che, sulla base di considerazioni stratigrafiche, è attribuibile alla fase di frequentazione tarda, fra fine III e I secolo a.C.

Fig. 65 - Pianta del settore centrale del pianoro sud-est con ambiente (F) relativo alla frequentazione tarda del pianoro.

Central portion of the south-east plateau with room (F) pertaining to the later frequentation of the plateau.

7L’edificio, composto da un singolo ambiente rettangolare (fig. 66), risulta costruito, successivamente ad una azione di ripulitura del pianoro e di scarico dei materiali, in un profondo pozzo circolare scavato nello scisto argilloso (diam. ca. 3 m.; profondità oltre m. 4) (fig. 67), adoperando il piano di tegole posto a ricopertura dello scarico stesso quale probabile piano pavimentale.

Fig. 66 - Pianoro sud-est: pianta dell’ambiente tardo (fig. 65, F), con pozzo di scarico.

South-est plateau: room F (on fig. 65) with the dump.

Fig. 67 - Superficie del pozzo di scarico livellata con frammenti di tegole e kalypteres.

Top of the dump closed by roof tile and ridgepole tile fragments.

8Purtoppo, i materiali assegnabili alla fase di uso dell’edificio stesso sono assai poco significativi, dato che esso era ricoperto da un sottilissimo strato di humus ma, significativamente, esso presenta un orientamento diverso da quello dei restanti edifici sul pianoro, (sulla cui interpretazione si veda Roccagloriosa I, 96 e fig. 100). Le dimensioni di m. 6x4, ci inducono a classificarlo nella categoria dei piccoli edifici abitativi rurali che, probabilmente, rimane in uso durante il periodo di utilizzazione dei diversi pianori che costituivano l’oppidum quali parti di un agglomerato rurale.

9Raffronti per le dimensioni possono rinvenirsi negli edifici rurali minori dei territori interni della Magna Grecia fra III e II secolo a.C. (Russo Tagliente 1992, 110).

1.4. Area Napoli

10È questo il nucleo abitativo che ha restituito la documentazione più abbondante e varia relativa al periodo in esame.

11In un paragrafo precedente (cap. 1.3.2) dedicato alla ceramica rinvenuta, è già stata analizzata la particolare documentazione di un gruppo di ceramiche molto probabilmente attribuibili ad un’area di necropoli sulla cd. Area U. Balbi. In questo contesto si presenterà qualche commento su quelle strutture abitative dell’Area Napoli propriamente detta (scavate nel 1971) che sono già state indicate quali appartenenti ad una fase diversa da quella di IV-III secolo a.C.

12Le strutture in questione si trovano all’angolo nord-est del plateau ed includono alcune costruzioni quadrangolari di uno o due ambienti (supra, 35-37). Sia le dimensioni che i materiali di superficie ad esse associabili (la macina rotatoria, infra, 1.4.1, e vari chili di spugne di lavorazione del ferro) lasciano pensare che si tratti di semplici unità abitative, includenti aree di lavorazione.

1.4.1. Macina rotatoria (fig. 68)

13Oltre alla ceramica, discussa nel paragrafo 2 del testo inglese, è di rilievo l’evidenza di manufatti d’uso, come la macina granaria del tipo rotatorio rinvenuta sul pianoro in questione (Roccagloriosa I, 309, n. 593) e molto probabilmente associata ad una delle abitazioni della fase di occupazione di II o I secolo a.C. Moritz (1958, 52), nella sua classificazione delle macine granarie, colloca il passaggio dal tipo hopper-rubber (v. Roccagloriosa I, fig. 202, n. 591-592) al tipo rotatorio nel corso della seconda metà del III secolo a.C.

14È da osservarsi che quest’area, dove abbiamo tracce più consistenti dell’abitato di II e I secolo a.C., costituisce topograficamente la parte centrale dell’abitato aggregato di altura. In base alla topografia e dimensioni delle ‘sopravvivenze’ di II e I secolo, sono da osservarsi utili raffronti con la situazione riscontrata a Valesio, in Messapia, dal recente progetto di ricerca olandese (Boersma 1990, 87-90; si raffronti, in particolare, la fig. 22 con la fig. 21).

2. Later pottery (2nd and 1st c. B.C.) from the Central Plateau

15As a result of our study of the later material from the extra-mural areas (supra, 41-47), we have been able to re-evaluate some of the ‘problem’ pieces found on the Central Plateau.

16After the landslide that covered the Central Plateau (Roccagloriosa I, 15, fig. 8) and preserved some of the architectural features such as the votive deposit, a kiln was built. A later landslide occurred which then covered the kiln area. The uppermost layers contained coarse ware that was very worn but different in form and manufacture than that found in the habitation layers pertaining to the major activity period of the site. Jugs with similar forms and manufacture had been found in a deposit in the kiln: those forms are presented in Roccagloriosa I. All of the later pieces from the Central Plateau are coarse ware, mostly jugs for liquids. In general it can be said that the forms are closely paralleled by forms from Cosa (Cosa 1976), Sutri (Sutri 1964, Sutri 1965) and, closer to the study area, Pompeii (drawings from P. Arthur). In addition to the so-called kiln deposit, these forms were spread uniformly across the Central Plateau in the upper layers immediately below the topsoil. The coarse ware forms span a period from ca. 275-250 B.C. to 40/30 B.C., thus chronologically corresponding to the ceramic evidence from the extra mural areas. The fine ware that is datable to the early part of the 3rd century consists of the grooved bowls which have been exhaustively discussed above. Other than that form, little fine ware was found that was datable to this period: a few Campana A sherds account for all of the fine ware.

17The presence of these later finds on the Central Plateau confirms substantially the picture of a weak continuity in the area through the later 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. The presence of the coarse ware with its clear later Republican influence is obviously to be connected in the first instance with the colonial foundation at Paestum in 273 B.C. and in the second instance with the colony at Buxentum of 196/184 B.C. Whether the people using these forms were “Roman” settlers rather than Lucanian “hangerson” cannot be determined: what can be postulated, however, is that their supply source was Roman as these forms are found throughout colonial foundations of the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. in all areas of Italy.

18One later piece of cooking ware, a nearly complete cooking pot, with signs of use, was very well made, with a smooth soapy to the touch surface and a very rounded body (Roccagloriosa I, no. 335): parallels for the piece are found at Settefinestre (Settefinestre 1985, tav. 54.5) and dated from the Trajanic to later Antonine period. This piece is quite different from all the other types and may indicate a later reuse of the kiln as an oven.

19The later material found in the kiln can be dated from the later 3rd century B.C. to the early 1st century B.C. A brief review of that material may prove helpful (Roccagloriosa I, nos. 306-336, 379).

20The pottery found inside the kiln is problematic in several ways. A misfired and overpainted black glaze bowl (Roccagloriosa I, no. 128) stuck to the kiln firing platform provides a terminus ante quem for the use of the kiln as a centre of pottery production. Another grooved but undecorated bowl (no. 336) was found outside of the kiln and could pertain to a later 3rd century production of the same form. On the other hand, the jars and ollae found in the kiln carry no traces of burning and could provide a date for the re-use of the kiln as a Storage place. Only the large casserole is fire-darkened although this piece was found beside the kiln and not actually in it. Nonetheless it most logically pertains to the phase when the firing platform was re-used. Two facts can be noted: 1) some of the jar and ollae forms are very long-lived but 2) despite a continuity of form, the high quality of the manufacture of the jars represents a break with the previous tradition and can most easily be explained by either a new supply source or a new production technique. Previous coarse ware pottery found at the site was characterized by a flakey and powdery surface with a great many quartzite and grog inclusions (see jar nos. 309, 308, 311 and cooking pot no. 321). All the other examples found in the kiln deposit are characterized by a wet-smoothed or lightly burnished very hard surface with a ‘soapy’ feel to the touch and a noticeable decrease in both the number and size of inclusions. Some of the ollae examples (nos. 316 and 324) were also found in the ‘Pozzo’ deposit: the closing of that deposit was postulated to have occurred in the latest years of the 4th century or the very early 3rd century B.C. on the basis that the grooved bowls were not found in the deposit. The ollae forms found in that Pozzo deposit were typical of the local pottery tradition in that they have the powdery surface and fabric described above. One amphora was found in the kiln: at the time of publication of Roccagloriosa I amphora no. 379 was considered as «perhaps assignable to Lyding Will’s type A (1982) series and thus datable to the later IV-early III century B.C.» At Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 106, 22 CE 1777/21) a similar form is called an “anforette” and dated to the end of the 3rd century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. and the more recent Gravina publication (Gravina II, fig. 85, no. 1536) includes a similar form referred to as “Baldacci type HA” and dated to ca. 200 B.C.

KILN DEPOSIT POTTERY CATALOGUE

Jars/Ollae (the numbers refer to the Roccagloriosa I entries)

21310: jug or one handled olla with a turned back rim, ovoid swelling body with a short neck. Simple strap handle. Wet-smoothed finish, few inclusions: perhaps fired at a higher temperature as most of the quarztite inclusions have dissolved. See Pompeii 1984, tav. 101, 2.CE287 for a generic parallel or tav. 100, 6.CE118. Both fall into the Olla type 4c variant with a long life span. See also Gravina (Small 1992, vol. 2, fig. 63, no. 1283) dated to the 2nd-1st centuries B.C. Clay 5YR 6/8 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 10.0 cm.

22308: similar form but with a powdery surface and more inclusions. The strap handle has a central groove. See Pompeii 1984, tav. 100, 5.CE1330 classified as type 3d which is characterized at Pomepii by a «fattura scadente». Clay 7.5YR 7/6 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 9.0 cm.

23309 and 311: similar form with a simple projecting rim. Long neck, groove on body below neck. Many white inclusions, powdery surface. Clay 7.5YR 7/6 reddish yellow. Rim diam range 9.0-11.0 cm.

24312, 314: jug/olla with a turned back rim and very sharply undercut lip. Very hard surface. See Pompeii 1984, tav. 101, 8.CE708, class 4e dated to the Hellenistic period. No. 312 Clay 7.5 YR 7/6 reddish yellow; no. 314 clay 5YR 6/8 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 10.0 cm.

25313: jug/olla with a slightly turned back rim, rounded and with a handle stub evident. Wet-smoothed finish, few inclusions. See Pompeii 1984, tav. 100, 10.CE144, class 4c as well as Lutti II, tav. 128, 12.CM6720/2, found in a level dated to before 40/50 A.D. Clay 5YR 6/6 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 10.0 cm.

26315, 323, 325: jug/olla with a simple turned back rim. Very hard surface. Small 1992, vol. 2, fig. 78, no. 1449 dated to Gravina VIIIa, late 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. Clay 5YR 6/6 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 8.0 cm.

27316: like 312 and 314 but with the beginning of a pouring spout. Very hard surface, few inclusions. See Pompeii 1984, tav. 104, 3.CE1329/2, “Hellenistic” and Luni II, tav. 133, 8.CM4467 dated to the first half of the 1st century B.C. Clay 5YR 6/8 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 22.0 cm.

28317, 319: jug/olla with a rounded rim and strap handle. Extremely hard surface, very few visible inclusions. Close to Small 1992, vol. 2, fig. 62, no. 1257 dated to Gravina Villa, late 2nd and lst centuries B.C. Clay 5YR 6/8 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 10.0 cm.

29318 and 323: exactly like 316 but without evidence of a pouring spout. Quite possibly non-joining pieces of the same pot. Same parallels indicated. Clay 5YR 6/6 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 22.0

30320: jug/olla with a large projecting rim. Extremely hard wet-smoothed surface. Few inclusions. Pompeii 1984, tav. 100.9.CE1614/4, class 4b, dated to before the middle of the 2nd century B.C. See also Luni II, tav. 140, 13.CM7800, dated to the 2nd century B.C., where it is classed as an amphora. Clay 5YR 6/8 reddish yellow. Rim diam. 6.0 cm.

31324: jug/olla. Simple rim but extremely hard surface. See Pompeii 1984, tav. 98, 3.CE122 classed as a 2c type olla and dated to the 2nd century B.C. Clay 2.5YR 6/6 light red. Rim diam. 11.0 cm.

Cooking Pots

32321: soft surface with numerous large white inclusions. See Small 1992, vol. 2, fig. 77, no. 1431 dated from Gravina VII through Villa which places it from the 3rd through the 1st century B.C. See also Roccagloriosa I, no. 235. Clay 7.5 YR 6/6 reddish yellow. Rim dimensions not ascertainable.

33326: Cooking pot with lid. Up-lifted rim. Clay 5YR 6/6 reddish yellow. See Small 1992, vol. 2, fig. 79, no. 1465 dated from the 4th to late 2nd-1st centuries B.C.; Cosa 1976, 22 II 64 dated to the first half of the 1st century A.D. and Settefinestre 1985, tav. 28.19 dated to the lst century A.D.

34335: actually found beside the kiln but associated with the kiln dump. Large two handled cooking pot. Very heavy piece. Rounded body, wet-smoothed with an extremely hard surface. No visible inclusions. See Luni II, tav. 125, 7.CM3815 dated from the 1st century A.D. onwards. Clay 5YR 5/6 reddish yellow. Rim. diam. 23.0 cm.

Amphorae

35379: Greco-Italic amphora. Composed of 5 joining rim sherds. Medium hard orange fabric (5YR 6.5/8) with abundant small angular inclusions (<1 mm), mainly of white and grey limestone, and rare minute mica. Regional production? See Roccagloriosa I (no. 379, p. 283 and fig. 191) for additional comments. Parallels found at Gravina (Small 1992, vol. 2, fig. 85, no. 1536) dated to ca. 200 B.C. and Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 106, 22.CE 1777/21 dated from the end of the 3rd century B.C. to the lst century A.D.

Black Glaze Pottery

36336: found beside the kiln but not in it. Compare with example no. 128 which is over-painted, thinner walled and thus, to be dated to the first half of the 3rd century B.C. This example is not over-painted and with much thicker walls and should most likely be dated to the second half of the 3rd century B.C. Not locally made.

37We should note that at Pompeii a distinction in the quality of production is also noted. Despite the long life of many of the forms contained in the kiln deposit the most chronologically significant pieces seem to be nos. 312, 324 and the amphora no. 379. We postulate that the deposit was put in the kiln near the end of the 3rd century B.C., although a date early in the 2nd century B.C. would not be completely out of line. It is highly unlikely that the deposit could be much later than the early 2nd century B.C. simply because it seems impossible to us that the kiln dome would have remained intact without repairs – for which there is no evidence – much later than that time. It may also be postulated that the pebble floor and and the lean-to roof covering the kiln may have been added during the time that the complex and upper plateau area was frequented although not inhabited. This may correspond to a brief increase in habitation activity in the extramural sites such as Mai and Calatripeda, and closer to the site in the Area Napoli, DB Area and lower Balbi Plateau in the Mingardo Valley or Gammavona and Santa Venere in the Bussento valley.

38Furthermore, other coarse ware forms are found on the Central Plateau which correspond to forms found at Roman sites, especially Cosa (Cosa 1976) and Sutri (Sutri 1964, Sutri 1965). Most of these forms, like those discussed above which were found inside the kiln, are datable from the mid-3rd to mid-1st centuries B.C., although mixed throughout the finds are forms datable to the later 1st to 3rd centuries A.D. The forms are not numerous, but they, like the later Roman amphorae, point to a reuse of the area in the late imperial period. Extended discussion of the late imperial use of the central and extra mural areas is deferred to Part II, Chapter 3.

39All the forms listed below were stratified in the layers above the collapse layer of the elite habitation complexes on the Central Plateau.

OTHER LATER POTTERY FROM THE CENTRAL PLATEAU

Coarse ware (fig. 69)

40• Base or stand (PC 1): larger version of Cosa 1976, PD 146 dated 110-40/30 B.C. The Cosa measurement is 6.8 cm. while this example has a diameter of 13.5. Most probably the foot for a votive louterion. Misfired.

41• Stand or base (PC 8): also possibly the base of a votive louterion. As PC 1 this piece is also misfired. Diam. 12.5

42The preceding two pieces are interesting and cannot be precisely dated. In addition to the Cosa parallel, several normal sized louteria bases have been found within the Hellenistic villa at Tolve (Tocco 1990).

43The diameter for those pieces is ca. 44 cm. Both examples (69793 and 68064) were found in room 11 which was a Storage room, plate XVIII, E and fig. 5 as well as p. 6 and note 18.

44• Jug/Olla (PC 11): Cosa 1976, PD 116 with a date of 110-40/30 B.C. and a dose parallel with Pompeii 1984, tav. 103, 4.CE2137 dated from the second half of the 2nd century B.C. through the Tiberian age.

45• Cooking Pot (PC 2): Cosa 1976, CF 21 275-150 B.C., also like Sutri 1965, A 97 dated to the late 2nd-early 1st and Minturnae (Kirsopp Lake 1934-35, 105, pl. 17c) dated to 240-230 B.C. Similar pots found also at Settefinestre (Settefinestre 1985, tav. 28.2 and tav. 28.3) dated from the Trajanic period through the late Antonine era. Also found at Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 104, 7.CE2242).

46• Cooking Pot (PC 3): Cosa 1976, CF 24 dated as above with parallels at Sutri (Sutri 1965, A 47), Min turnae (Kirsopp Lake 1934-35, pl. 17 d, f). Tyrrhenian Common Ware type. See also Genova 1993, CT 5, fig. 61/8 with a date of late 2nd-early 1st century B.C. as well. Also found at Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 97, 6.CE 1998/1) with a 3rd to 2nd century B.C. postulated.

47• Cooking Pot/Olla (PC 4 and PC 5): listed together because they are examples of the same form; see Cosa 1976, FG 24 mid 3rd to 2nd century B.C. (PC 5): with numerous parallels in the kiln deposit, see supra, 85-86, and Sutri 1965, form 39, A97 dated to the 2nd-1st centuries B.C. See also Cosa 1976, CF 16, dated 275-150 B.C. and Settefinestre 1985, tav. 28.1 found primarily in Trajanic through later Antonine contexts. Found also in Southern Italy at Vittimose (Dyson 1983, no. 47) and at Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 101, 8.CE708) with a later 3rd through 2nd century B.C. date.

48• Cooking Pot/Olla (PC 6): later form of PC 4 and 5, with a more hooked rim. Settefinestre 1985, tav. 30.4 dated to the later Antonine period while the same form is dated at Ostia III, tav. LVIII, fig. 502 to the 2nd century A.D., at Cosa (Cosa 1976, PD 126) dated to the 1st century A.D. and Luni I, tav. 75, fig. 3 dated from the 1st century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D. See also Pompeii 1984, tav. 104, 3.CE1329/2 where no date is postulated.

49• Jug/Cooking Pot (PC 7): Cosa 1976, CF 32 275-150 B.C. with a parallel al Sutri (Sutri 1965, A 89-92) dated to the late 2nd-early 1st century B.C. Also found at Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 100, 10.CE144) with a general date of “Hellenistic”.

50• Jug/Cooking Pot (PC 9): Parallels found only at Vittimose (Dyson 1983, 106) and 107 with a probable date from the 2nd century B.C. onwards.

51• Cooking Pot (PC 14): Cosa 1976, CF 45 275-150 B.C. with another generic parallel at Pompeii (Pompeii 1984, tav. 92, 5. CE488) dated from the 2nd century B.C. onwards.

52• Cooking Pot (PC 20): Sutri 1964, form 36, 149 dated to the Julio-Claudian period. Somewhat like Cosa 1976, VD 24), dated 125-40 B.C.

53Cooking Pot (PC 10): Settefinestre 1985, tav. 27.9 dated to quite late but also Pompeii 1965, fig. 2.9 dated to the 1st centuries B.C. and A.D.

54• Pelvis (PC 15, 16, 18): Assoro tomb 7bis, mid 3rd century B.C. (Morel 1966) and Vittimose (Dyson 1983, no. 108, fig. 150. See also Pompeii 1984, tav. 94, 5.CE143.

55Bowl (PC 12): Cosa 1976, VD 75 dated to ca. 125-60/70 B.C.

56Bowl (PC 17): Cosa 1976, PD 112 dated to ca. 110-40/30 B.C.

57What type of use of the site are we dealing with during this period of the mid-3rd through early 1st centuries B.C.? The quantity of coarse ware within the fortification walls indicates, above all, agricultural activity, just as it does in the extramural areas. There was one later cooking pot (dated ca. 1st century-3rd century A.D.) amongst the greater quantity of jugs found in the kiln deposit. Jugs or receptacles for liquids are practically the exclusive form found in the upper layers covering complex A. It is not to be excluded that the kiln may have been re-used as an oven in even the later centuries A.D. as there are a number of forms which may be dated to that time period. The various re-use phases, one in the mid 3rd through 1st centuries B.C. and again in the later 1st through 3rd centuries A.D. would explain the quantity of very worn and fragmentary coarse wares found throughout the superficial layers covering the Central Plateau. Fine wares occur in the lower extra-mural terraces, which presumably were less fragile geologically, but even there, the quantity of fine wares present is rather scanty. The huge lead pottery clamp, although undatable, found in one of the buildings also indicates agricultural Storage and repair of valued large Storage vessels. Possibly the abandonment of the area was not hurried and the few possessions that these stragglers had may have been bundled up and taken with them when they left. With the exception of the later 1st-3rd century A.D. examples in the Central Plateau, the DB Area and Area Napoli, the entire ceramic assemblage dated to the mid-3rd-early 1st centuries B.C. is comparable to the type of material found at many later 3rd-early 1st century B.C. rural sites in Apulia, Etruria and Sicily.

58As far as we can tell from the survey and limited excavation, we are not dealing with villae rusticae although such complexes are known in the nearby Vallo di Diano at the end of the 2nd century B.C. (Coarelli 1981a). The area within the old fortification walls did not develop into a vicus like the Celle/Morigialdo site. Nor does the evidence allow us to postulate developments like those found at Tricarico or Macchia di Rossano (Canosa 1990) or Moltone/Tolve (Russo Tagliente 1992, 173-181). At Tricarico a domus (probably later 2nd century B.C.) was built within the Lucanian oppidum. An earlier mid-3rd century small dry wall existed at Tricarico in the second half of the 3rd century B.C.: a pianta pedis tegula stamp has been associated with this wall. At Roccagloriosa, on both the Central Plateau and in the lower plateaus, dry walls dated to the mid-3rd century have been found. The indigenous Italic, or Hellenic if one prefers, building practices or techniques continue to be utilized in Southern Italy-particularly for agricultural uses-long after a complete Romanization of the area (Torelli 1981). Additionally, one planta pedis tile stamp has also been found (Roccagloriosa I, fig. 200, no. 557) but at most, we are dealing with the simple and scanty remains of farmhouses much like those discussed in Part II, chapter 2 on the ‘transitional’ sites. A cultural change is not very evident in the actual material remains although the unguentaria and Roman coarse wares are obviously indications of a new market. The placement of the establishments in the areas immediately outside of the old nucleated center is significant, as is the fact that the earlier monumental complex on the Central Plateau seems to have been reduced to a workshop area.

59The presence of Italian terra sigillata as well as the later amphorae discussed above on the lower plateaus is not quantitatively significant but it does indicate continued activity or frequentation in the area after ca. 40/30 B.C., as is documented for the greater territory during that period (infra, Part II, Chapter 3). In fact, the Dragendorff bowl form first appears in ca. 30 B.C. but is particularly popular in the Augustan period. The Italian terra sigillata pieces from the DB Area and the Italian terra sigillata from Monaci all correspond to an increased Augustan presence in the area in general, and are quite possibly the hints of an elusive larger and long-lived establishment at Monaci/Vallone Cupo (site no. 2, infra, Part II, Chapter 3). Still the material is not sufficient quantitatively to indicate a strong Augustan presence specifically in either the extra-mural areas or within the long abandoned fortification walls.

60As is the case for the ‘transitional’ sites discussed in Part II, Chapter 2, an early Roman market source is evident in both the Campana fragments and in the Roman coarse ware examples, which may be direct imports or Roman inspired copies. The absolute quantity of either product is difficult to evaluate because of the extremely poor state of conservation and the extreme fragmentation of the pieces found in the upper layers which covered the entire complex of three houses on the Central Plateau. A Roman market center in the later 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. is significant in itself because it provides evidence for both a passive Romanization based on a gradually increasing economic dependence and a breakdown of local artisan traditions. Nonetheless, the trade up and down the Tyrrhenian coast in coarse wares began early in the century, although the 2nd century B.C. was perhaps the time of greatest saturation. As far as Buxentum is concerned, Livy (39, 23,3-4) notes that the city was found semideserted ten years after its foundation. The remark implies that the state of the colony was not generally known and that it was a largely unimportant colony. Still, even unimportant colonies had kilns producing coarse wares and roof tiles, etc. Fine wares could also have been produced, but we should not forget the proximity of Paestum, which could have provided that which the Buxentum colonists lacked or did not produce for themselves. Even if Buxentum were not a thriving colony, Roman wares pro duced in centers along the Tyrrhenian coast such as Minturnae, Sinuessa and Pompeii were certainly being shipped to other areas. The mass production of Roman wares in various centers of Campania and Latium and their distribution by sea is a well-known fact (Genova 1993; Py/Lebeaupin 1986; Rayssiguier 1983; Morel 1981).

61At Paestum in the 2nd century B.C., there is substantial geophysical and written evidence for a lengthy disturbed period, as is the case also at Sipontum and Buxentum. At Paestum the disturbance has been reasonably associated with a silting up of the river Salso and possibly a concomitant bradysism (Kahrstedt 1960, 3, n. 1; Mello 1974, 137-145). On the basis of limited survey and excavation in these upland areas, it would be false to assert that the presence and/or frequentation of the extramural areas during the 2nd century B.C. is attributable to swampy conditions at Buxentum and in the lower Bussento river valley in general. Nonetheless, we should consider this hypothesis in the light of the settlement at Celle di Bulgheria on a high terrace overlooking the inland Mingardo river valley: that site is the first area inhabited during the 2nd century B.C. or in that period which could be called ‘early Roman’. We can also remember that Buxentum as a colony had serious problems in the early to middle 2nd century B.C. To date, the earliest Roman settlement found on the Bussento valley floor is at Vallone Pantana, where initial settlement seems to occur in the late 1st century B.C. as the evidence contains, among later wares, some Italian terra sigillata. Further down the coast, the late republican villa at Sapri gives a good indication of the earliest Roman seaside establishments, indicating that by the mid 1st century B.C. whatever unfortunate conditions existed along the coast in the 2nd century B.C. had passed.

3. Comments on the later pottery evidence

62To sum up. Although the ceramic evidence discussed above is from mixed stratigraphic contexts, the grouping of artifacts reveals two clear divisions in the chronology of habitation for all the extramural areas. First, habitation material similar to that within the fortification walls reflects both the floruit and decline of the site by the second half of the 3rd century B.C. A second artifact group reflects a limited usage of the areas from (on the basis of the black-glaze dates) ca. the second half of the 3rd century B.C. onwards with more intense usage after ca. 200 B.C. which largely corresponds to the increased Roman presence in the immediate area at Buxentum.

63The question becomes more problematic when the type of material present for the period after ca. 200 B.C. is considered. The later black-glaze pottery from the Area Napoli consists mostly of paterae, not normally found in habitation levels. On the other hand, all the later coarse ware – cooking pots, louteria, jugs – is typically found in habitation levels. The bowl of undecorated Italian terra sigillata practically marks the end of the use of the Area Napoli. It seems possible that, in addition to later habitation testified to by the coarse ware, there may have been a shrine beside the road. What purpose such a shrine may have served can only be guessed at, but it may have served to mark the boundary of the vicus, by then well established at Celle di Bulgheria or, in fact, to mark the division of cultivated and uncultivated land, or the division between public and private lands.

64In the DB Area there was an enormous mass of material but very little fine ware was retrieved that can be dated to the later period. Some coarse ware – not a great quantity – can be attributed to the decades after ca. 200 B.C.

65The later black glaze pottery in the C. Balbi Plateau consists of more varied forms than were found in the other two extra-mural areas under consideration. Here, the black glaze forms are mostly bowls while the coarse ware is represented by a majority of jugs.

66On the basis of the foregoing summation, we can postulate that, in the later 3rd to early 1st centuries B.C., several small complexes could be found on the lower plateaus. At least one burial can be postulated there on the basis of the unguentaria, as well as some continued/residual cultic activity in the areas outside the fortification walls below the major entrance to the oppidum. By the mid 1st century B.C. or even earlier in that century, these small farmsteads seem to have disappeared. The land probably was agglomerated into larger holdings such as Monaci/Vallone Cupo or Calatripeda or, more likely even closer, to Santa Venere. By the mid 1st century B.C., then, the upper terraces of the Mingardo valley seem to have been deserted. The history of the extra-mural areas is closely connected, first, with the vicus at Celle and the colonial foundation at Buxentum, and second, with the more dense Roman occupation of the Bussento valley from the second half of the 1st century B.C. onwards.

4. Considerazioni conclusive

- 5 Una recente sintesi del quadro storico, che non trascura tuttavia certi aspetti dell’evidenza arche (...)

67Sia i dati sulle strutture di abitato che la documentazione della ceramica per il periodo successivo alla metà del III secolo a.C. non lasciano dubbi sulla profonda trasformazione subita dall’oppidum. Anche se non vi sia alcun elemento che lasci pensare ad una distruzione violenta o abbandono repentino, è chiaro che il radicale restringimento dell’abitato e soprattutto la evidente cesura nella documentazione delle necropoli sono indizi di una mutata funzione dell’insediamento aggregato di altura nella nuova situazione venutasi a creare in Lucania e, più in generale, in Magna Grecia nel corso del III secolo (Torelli 1992a; Torelli 1992b)5. I raffronti archeologici per situazioni analoghe sono innumerevoli sia nell’ambito stesso dell’area lucana (Laos, Serra di Vaglio, Oppido Lucano/Montrone, Cersosimo, per limitarsi ai siti oggetto di recenti ricerche), che in area brettia. Tuttavia, si è più spesso, e talvolta in maniera eccessiva, posta l’enfasi sulla frattura netta, trascurando (spesso a causa della non sistematicità dei dati archeologici disponibili per questo periodo di profonde trasformazioni) quegli aspetti di continuità abitativa sia pur collegati ad un contesto politico, economico e territoriale profondamente mutato. Si considerino, a tale riguardo, i casi di Eboli/SS. Cosma e Damiano (Maurin 1976); Tricarico tempietto e casa di I sec. a.C. (Canosa 1990 e, più di recente, Cazanove 1996); Gravina, anche se nell’area apula (Small 1992); Arpi, con casa ellenistica a peristilio (Mazzei/Mertens/Volpe 1990); infine, gli edifici repubblicani di Valesio, in area messapica (Boersma 1990, fig. 23). Nel caso di Roccagloriosa, tuttavia, ad una documentazione sufficientemente ampia per quanto riguarda la ceramica soprattutto per le aree extra-murane (supra, cap. 1), ed altri oggetti d’uso (anfore, macina – fig. 68, supra) per cui la documentazione proviene soprattutto da ricognizioni (ma che, data l’esplorazione estensiva di questo oppidum può considerarsi pienamente rappresentativa dell’effettiva situazione abitativa antica), non corrisponde una eguale evidenza a livello di strutture edilizie, che ci possa fornire un quadro delle presenze abitative meno generico di quello relativo all’esistenza di edifici rurali per lo sfruttamento agricolo. Forse, l’immagine più eloquente della radicale trasformazione subita dall’abitato dopo la fine del III secolo è fornita dalla carta di distribuzione dei reperti riferibili al periodo fine III-I sec. a.C. e la pianta che fornisce l’estensione dell’area abitativa presunta (fig. 70), sulla base dei reperti e delle strutture abitative sopra discusse. L’evidente raffronto con l’unico altro sito magno-greco per cui è stata tentata una simile ricostruzione (Valesio, in Boersma 1990, fig. 21-22) può forse fornire qualche indizio meno vago sulle vicende dell’oppidum nel periodo successivo alla guerra annibalica.

Fig. 70 - Estensione delle aree di frequentazione dell’oppidum stimate sulla base dei rinvenimenti. 1: aree di abitazione di IV-III sec. a.C.; 2: ritrovamenti sporadici meno densi pertinenti alle aree di abitazione di IV-III sec. a.C.; 3: aree di abitazione di II-I sec. a.C.

Areas of frequentation estimateci on the basis of the finds and the structures. 1: habitation areas, IVth-IIIrd c. B.C., 2. less dense scatters pertinent to IVth-IIIrd c. B.C.; 3: habitation areas, IInd-Ist c. B.C.

- 6 È significativo che nonostante la presenza di materiali ceramici di età imperiale non vi sia alcuna (...)

68Infine, un dato assai interessante che emerge dallo studio delle fasi abitative più tarde è quello fornito dalla ricognizione intensiva del territorio ‘vicino’ ossia delle aree collinari e pianeggianti tutt’intorno al crinale del M. Capitenali (su cui era collocato l’oppidum) entro un raggio di 4-5 km. È su queste zone di pendice o pianeggianti che ritroviamo tre chiari esempi di agglomerazioni di edifici rurali, con una estensione variabile fra due e tre ettari (Mai, Scudiere, Celle/Morigialdo – infra, Parte II, cap. 2), che nel corso del IV secolo (più specificamente la seconda metà) si affiancano all’oppidum, costituendo un elemento intermedio della gerarchia insediativa fra il sito centrale e le “fattorie” sparse. Sono proprio questi siti (definiti quali ‘transizionali’), con una documentazione per il II e I secolo assai più varia, che, con la loro vitalità e nelle mutate condizioni territoriali, vengono gradatamente a soppiantare l’oppidum6 per poi in parte ereditarne le funzioni abitative nel periodo romano-imperiale.

69L’impressionante sviluppo del vicus di Celle/Morigialdo fra il I ed il III secolo d.C. (infra, Parte II, cap. 3), grazie alla sua particolare collocazione nel nuovo sistema insediativo venutosi a creare in un momento successivo alle deduzioni triumvirali e ad una probabile rivitalizzazione augustea della colonia di Buxentum (Gualtieri 1996a), rappresenta forse l’elemento più vistoso di un tale processo e ci fornisce un utile filo conduttore delle vicende insediative nel comprensorio.

Anexos

Notas

1 Il tesoretto includeva 18 monete di argento ed una di bronzo provenienti da svariate zecche della Magna Grecia, fra cui sono preminenti Taras, Kroton, Heraklea e, molto probabilmente, Elea (Fiammenghi et al. 1996).

2 Si consideri, in particolare, il tesoretto monetale rinvenuto in una casa dell’abitato sul Montrone (Oppido Lucano) la cui deposizione è stata datata alla metà del terzo secolo a.C. (Panvini Rosati 1975). Un esempio ben documentato di continuità abitativa, sia pur nel contesto di un evidente processo di ristrutturazione, fra III e II secolo a.C., è ora fornito dall’oppidum di Tricarico (MT): si veda Cazanove 1996.

3 Nonostante un evidente scadimento del livello di vita nell’oppidum nel corso del III secolo, si tratta pur sempre di presenze abitative di un certo rilievo, tenuto conto dell’evidenza fornita dalla ceramica a vernice nera databile fra la seconda metà del III sec. a.C. e la prima metà del II, nonché la importazione di anfore del tipo transizionale Greco-italico/Dressel IA.

4 Si consideri il piatto di ceramica campana, databile alla metà del II secolo a.C. rinvenuto nell’Area Napoli (supra, cap. 1, 39-40).

5 Una recente sintesi del quadro storico, che non trascura tuttavia certi aspetti dell’evidenza archeologica, è quella di Lomas 1993.

6 È significativo che nonostante la presenza di materiali ceramici di età imperiale non vi sia alcuna evidenza di sostanziale trasformazione degli edifici adoperati – ad es. uso di opera cementizia – in stridente contrasto con la diffusione di tecniche edilizie specializzate, quali l’opus reticulatum, nell’area costiera adiacente – a Sapri/Santa Croce.

Índice de ilustraciones

| |

|---|---|

| Leyenda | Fig. 61 - Pianoro Centrale: muretti di contenimento sul declivio immediatamente ad est del Complesso A.Central Plateau: small terracing wall on the slope immediately to the east of Complex A. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-1.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 404k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 62 - Pianoro Centrale: scarico lungo il lato esterno (est) del muro posteriore del portico.Central Plateau: dump along the exterior (eastern) side of the back Wall of the portico. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-2.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 288k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 63 - Pianoro Centrale: muretto tardo (F 185) sovrapposto alle strutture di IV secolo a.C. (muro in mattoni crudi/argilla su zoccolo di calcare F 205) del Complesso B (da nord-ovest).Central Plateau: later wall (F 185) put on top of the 4th c. B.C. structures (wall in unbaked clay on a lime-stone socle F 205) in Complex B (from the northwest). |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-3.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 352k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 64 - Idem, da nord.Idem, from the north. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-4.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 312k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 65 - Pianta del settore centrale del pianoro sud-est con ambiente (F) relativo alla frequentazione tarda del pianoro.Central portion of the south-east plateau with room (F) pertaining to the later frequentation of the plateau. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-5.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 200k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 66 - Pianoro sud-est: pianta dell’ambiente tardo (fig. 65, F), con pozzo di scarico.South-est plateau: room F (on fig. 65) with the dump. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-6.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 248k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 67 - Superficie del pozzo di scarico livellata con frammenti di tegole e kalypteres.Top of the dump closed by roof tile and ridgepole tile fragments. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-7.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 172k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 68 - Macina rotatoria dall’Area Napoli.Rotary mill, Area Napoli. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-8.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 128k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 69 - Later pottery from the Central Plateau.Ceramica tarda dal Pianoro Centrale. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-9.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 140k |

| |

| Leyenda | Fig. 70 - Estensione delle aree di frequentazione dell’oppidum stimate sulla base dei rinvenimenti. 1: aree di abitazione di IV-III sec. a.C.; 2: ritrovamenti sporadici meno densi pertinenti alle aree di abitazione di IV-III sec. a.C.; 3: aree di abitazione di II-I sec. a.C.Areas of frequentation estimateci on the basis of the finds and the structures. 1: habitation areas, IVth-IIIrd c. B.C., 2. less dense scatters pertinent to IVth-IIIrd c. B.C.; 3: habitation areas, IInd-Ist c. B.C. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-10.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 320k |

| |

| Título | Central Plateau. Tables of Pottery from strategic layers |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-11.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 376k |

| |

| Título | South-east Plateau |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-12.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 64k |

| |

| Título | Habitation area north of Central Plateau - Edificio ‘pubblico’. VA-XA-WA layers |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/docannexe/image/2529/img-13.jpg |

| Archivo | image/jpeg, 234k |

Salvo indicación contraria, el texto y otros elementos (ilustraciones, archivos adicionales importados) se puede utilizar bajo licencia OpenEdition Books License.