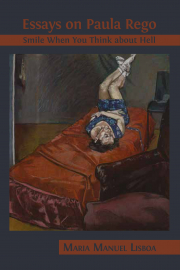

Essays on Paula Rego

|4. An Interesting Condition: The Abortion Pastels

Texto completo

Renoir […] is supposed to have said that

he painted his paintings with his prick.

Bridget Riley, ‘The Hermaphrodite’

Thus I learned to battle the canvas, to come to know it as a being resisting my wish (dream), and to bend it forcibly to this wish. At first it stands there like a pure chaste virgin… and then comes the wilful brush which first here, then there, gradually conquers it with all the energy peculiar to it, like a European colonist.

Wassily Kandinsky

Mignonne, allon voir si la rose

Qui ce matin avoit declose

Sa robe de pourpre au soleil,

A point perdu cette vesprée,

Les plis de sa robe pourprée,

Et son teint au vostre pareil.

Pierre de Ronsard

Christmas by Any Other Name

1In James Cameron’s film of 1984, The Terminator, we are treated to a futuristic rendition of the Nativity with assorted complications. A cyborg travels from the future to the diegetic present to kill Sarah Connor, a woman who, at an unspecified but prophesied date, will give birth to a child at that point still to be conceived. The child, John Connor (a good Irish-American Catholic name, which furthermore shares the same initials as Jesus Christ’s), will live to be the saviour of humanity against the cyborgs that in the near future are due to take over the planet. Hot in pursuit of the cyborg is Kyle Reese (a name which is a near homophone of the ancient Greek liturgic call ‘kyrie eleison’: God have mercy), an envoy of those future humans and a friend of Connor’s, who is dispatched to prevent the murder, and to ensure that the would-be mother survives and brings forth the necessary saviour. He does more than that, and in fact impregnates her with the foretold child. The film develops into a straightforward plot of quest and struggle, pitting brains against brute force, orderly civilization against the unbridled techno-elemental, good against evil. In the course of the film, the search for the woman to be slaughtered becomes merely a pretext for the real business of males — human and otherwise — killing each other in the name of prioritizing their respective lineages. Good achieves an open-ended victory (the cyborg is defeated but there are plenty more — and several film sequels — where he came from), albeit, in true Gospel fashion, only at the price of a sacrificial male death. Reese, whose persona — beyond the figure of knight in shining armour in aid of damsels in distress — had adumbrated the triple role of God (father of a Saviour), guardian angel (of unborn children) and Saint Joseph (his son will bear his mother’s rather than his father’s surname, and therefore paternity appears to be a by-proxy affair), dies, leaving us with one surviving heroine and the promise of a living hero in the future. There is of course an important difference between these two. A bird in the hand is always better than two in the bush, and the survival chances of the two sexes at the end look unequal: on the one hand a resilient heroine who at the very last ceases to rely upon ineffectual defenders and takes it upon herself to finish the job of destroying the cyborg. And on the other hand, a dead hero and a promising but yet unborn son.

2This scenario encompasses much that is relevant to the themes of male death, female survival and self-destructive male lineages discussed in previous chapters. In The Terminator, in a reversal of the Father Amaro series (figs. 3.1; 3.2; 3.4; 3.5; 3.7–3.9; 3.12; 3.14; 3.19–3.21; 3.23; 3.27) and indeed of the Gospel texts, a son sends his future father to his death in order to save himself/his interests, and males engage in mutual destruction (man against cyborg in a cross-species echo of clergymen against secular masculinity — Amaro versus João Eduardo in The Sin of Father Amaro). The results are not dissimilar, tending towards the effect of gender disloyalty among males and mutually-forsaking relatives: God and his son on the cross, Connor and his sacrificed father in different time dimensions, humanity against the cyborgs that we presume were its highest-tech offspring. The Terminator’s themes of nativity and infanticide, or salvation and perdition, are akin to the central considerations of the images that will now be discussed: namely the inclusion of intertextual allusion (to prior traditions — whether theological or aesthetic) and terror. And at the heart of both film and images lies the patriarchal/theological determination to control female reproduction (the birthing of babies) in the name of male perpetuity.

3I shall now consider a series of ten pastels produced by Paula Rego from fourteen sketches over a period of approximately six months, between July 1998 and February 1999. As so often in Rego’s work, only more directly so in this case, her images are rooted in a pre-existing context whose nuances inform the resulting pictures, and are central to their meaning. The motivation behind these particular works was a political event in Portugal, namely the referendum on a law just then approved by parliament, which liberalized the existing abortion regulations. Like many European countries, Portugal has a strong constitution, and it is unconstitutional to hold a referendum on a law already approved by parliament. But a powerful lobby promoted largely by Roman Catholic interests brought sufficient pressure to lead the President of the Republic to approve an (unconstitutional) referendum. The referendum took place on 28 June 1998. Its result, details surrounding which will be outlined presently, was to bring about the suspension of the law, for the purpose of its subsequent re-submission to Parliament. This chapter will seek to place the pastels and sketches, which are almost unprecedented for this artist in remaining untitled, within the context of the political upheaval of events surrounding the controversy, as well as within the wider scenario of abortion debates worldwide.

4In an interview given in the year these works were produced, and with reference to them, Paula Rego said that to her, death never signifies redemption. ‘Death means you die. That is all’ (Rego quoted in Marques Gastão, 1999, 44). Her work throughout the decades, as discussed previously in relation to works such as The Maids (fig. 1.4), Girl with Chickens (fig. 3.8) and The Coop (fig. 3.12), has repeatedly manifested the inability or unwillingness — idiosyncratic within the canon of Western art — to cast the woman as victim. This identifying hallmark becomes more noticeable in those cases in which she departs from an originating text (Genet’s The Maids; Eça de Queirós’s The Crime of Father Amaro) whose plot centres on a female death. It is curious that, having opted for such texts, Rego circumvents the primary narrative motivation: in The Maids (fig. 1.4) by casting a man in drag in the role of the female murder victim; and in The Crime of Father Amaro (figs. 3.1; 3.2; 3.4; 3.5; 3.7–3.9; 3.12; 3.14; 3.19–3.21; 3.23; 3.27), even more tortuously, by emphasizing survival and revenge where the original narrative had depicted the woman’s defeat and death. In the abortion series to be discussed now (figs. 4.3–4.5; 4.14; 4.15; 4.24–4.26; 4.30; 4.31; 4.37; 4.38; 4.41; 4.49), her female protagonists come arguably closer than ever before to surrendering to adverse circumstances. The bloodshed of the abortion room appears to signpost their pain more intentionally even than it does the death of the foetus, which is nowhere to be seen. These images about abortion, then, focus exclusively on maternal suffering: a profane mater dolorosa prioritized over a dead son. In Rego’s work the girls and women suffer, but none is actually dead, and the depicted trauma becomes itself the encoded script for a battle fought and won. A battle, as the subsequent argument will elaborate, whose contenders may not after all be the obvious ones of unwilling mother versus aborted foetus, but instead a gallery of women, girls and unborn children pitted against the customary enemies of church and state in Rego’s unquiet universe.

5What emerges from the abortion polemic that gave rise to these pictures is the fact of the Catholic Church’s continued influence in national politics in Portugal, even following the establishment of democracy in 1974. I wish to begin by elaborating upon some points regarding the church’s long-standing intervention in public affairs (specifically sexual politics) in general, and in Portugal in particular.

Infallible Fallacies

- 1 Anti-abortion activism in the United States may include but does not necessarily entail a Catholic (...)

6Referring to Machiavelli’s principle of a form of morals without scruples, such that the basis for success is that might is right, Lloyd Cole contends that this concept accurately describes the impact of the Roman Catholic Church in countries where it exercises significant control over the population, and over its reproductive — including contraceptive — practices (Cole, 1992, 51). Janet Hadley gives a lucid account of how the abortion controversy has set the agenda of wider national politics at various points, or in some cases more or less perennially, in countries such as Ireland, Poland, Germany and the United States. In March 1993 a gynaecologist, David Gunn, was killed by anti-abortion activists1 outside his Florida clinic, and since then the violence perpetrated by those who without irony call themselves ‘pro-life’ has escalated with further killings. Subsequent to this, and regardless of pressure from some sectors of the Catholic faithful who distanced themselves from the ‘vengeful Old Testament mentality’ of ‘extremists who have hijacked the American pro-life movement’ (Hadley, 1996, 153), in March 1995, two years after that first killing in the United States, Pope John Paul II issued his eleventh Encyclical, Evangelium vitae (‘Gospel of life’). In it he urged all Catholics to consider themselves under a ‘grave and clear obligation’ to join non-violent anti-abortion protests. ‘The pope’s message came within inches of endorsing anti-abortion militancy as a religious duty and the mainstream lobbyists fretted that it would whip up the fanatics to further image-damaging antics’ (Hadley, 1996, 154).

- 2 For religious objections to pain relief in childbirth see William Camann, ‘A History of Pain Relief (...)

7Not surprisingly, then, both before and after this papal encyclical, anti-abortion Catholic thought, as well as the extremist factions of the non-Catholic anti-abortion lobby, have continued to equate abortion with genocide and with the euthanasia practices of the Nazis against the physically and mentally handicapped. In this context, some writers have come to view the opposition to abortion as operating in tandem with an implicit declaration of wider sexual-political import (the claim of control by patriarchy, church and state over the bodies and roles of women), a declaration that furthermore entails a theological/doctrinal dimension. This refers primarily to the Christian/Roman Catholic view that the reproductive function is the paramount role of women, ordained as either a punishment (childbirth in pain as collective punishment of women for Eve’s original sin)2 or as a privilege (the emulation of the Virgin Mary as Holy Mother). In either case, motherhood emerges as neither a choice nor an option, but rather as a divinely ordained imposition.

8In Genesis, God admonishes Eve that in retaliation for her disobedience ‘I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee’ (Genesis 3: 16). In this passage, woman’s criminality, her maternity, and her subjection to the male are neatly linked together and transmitted in perpetuity to all womankind. To all womankind, that is, until the advent of Mary, whose redemptory coming into being had the power if not fully to cleanse, at least to set a good example to her fellow women. Her all-embracing purity beautifies even Eve’s sin, which it transforms it into a felix culpa, a Fall now blessed for having made Mary’s own idolized existence necessary (Warner, 1985, 60–61). Childbirth, and more specifically the pain it entails, was the punishment for the woman’s greater portion of blame in the scenario of original sin. Both the womb and the child in it were stained by that sin: ‘Woman was womb and womb was evil’ (Warner, 1985, 57), therefore woman was evil too. That syllogism endured until the advent of a Marian worship whose essence was likewise maternity, but now a hallowed, purifying and redemptory maternity to which other women could aspire, while however, paradoxically, being conscious that as sinners they could never fully replicate it.

- 3 See Eamon Duffy, ‘True and False Madonnas’, The Tablet (6 February 1999), 169–71, for a discussion (...)

9Under Vatican doctrinal ruling, Mary stands to this day as the exception to the human and female plight in two respects: she is exempt from original sin and she achieved motherhood while retaining her virginity, or, as the well-loved hymn would have it, ‘Mother and Maiden was never none but she, /Well may such a lady Godde’s mother be’.3 At an abstract level, therefore, as suggested above, she represents a philosophically and emotionally insurmountable problem for women: she is held up as that which they ought to strive to be whilst being admonished that, being different from her in those two respects, they can never approximate her privileged status (Warner, 1985, 337). And at a more pragmatic level she has become the vehicle for the promotion of a series of political and ideological interests that relied upon the reproductive subjection of women as one of its central tenets:

In Catholic countries above all, from Italy to Latin America […] women are subjugated to the ideal of maternity. […]

The natural order for the female sex is ordained as motherhood and, through motherhood, domestic dominion. The idea that a woman might direct matters in her own right as an independent individual is not even entertained. In Catholic societies, such a state of affairs is general, and finds approval in the religion’s chief female figure. (Warner, 1985, 284, 289)

The writer of the above lines goes on to elaborate upon how propaganda of this sort, and the conflicts it throws up, extend well outside the sphere of theological debate and into real politik:

In 1974 Pope Paul VI, sensitive to a new mood among Catholic women, attempted to represent [Mary] as the steely champion of the oppressed and a woman of action and resolve. She should not be thought of, he wrote, ‘as a mother exclusively concerned with her own divine Son, but rather as a woman whose action helped to strengthen the apostolic community’s faith in Christ’. (Warner, 1985, 338)

When Pope Paul VI held up Mary as the New Woman, the model for all Christians, he expressed this impossibly divided aim without irony, in the immemorial manner of his predecessors. The Virgin is to be emulated as ‘the disciple who builds up the earthly and temporal city while a diligent pilgrim towards the heavenly and eternal city’. (Warner, 1985, 337)

Earlier dictates of this sort, as we have seen, were put to use in Portugal by the propaganda machinery of the Estado Novo. Their effect, however, outlasted the fall of the regime, as demonstrated by the nature of the polemic that came to surround the abortion referendum a quarter of a century later. Before moving onto this later period, it is useful to note the analogies between, on the one hand, the censorship apparatus of dictatorship, as deployed in Salazar’s Portugal and analogous regimes, and on the other, the older tradition of mono-vocal papal pronunciation. The latter dates back to the establishment by Pius IX of the dogma of papal infallibility in 1870, and has found confirmation in a series of subsequent Vatican utterances. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Pius X instigated a campaign that culminated in the enforcement of an anti-modernist oath imposed upon all Catholic ordinands. Its intention was to curtail intellectual attempts by theologians to reconcile Catholic beliefs with science, democracy and an objective account of history:

[The anti-modernist oath] involved assent to all papal teaching, both as to content and as to the ‘sense’ in which the Vatican meant it to be understood. Such internal assent went beyond anything dreamt up even by Stalin or the worst imaginings of George Orwell. The oath survives to this day in a new but similarly encompassing formula taken by Catholic ordinands, seminary teachers and Catholic university theologians. The pernicious result of Pius X’s campaign was the shackling of free and imaginative Catholic thinking, discussion and writing for the next 50 years. (Cornwell, 1998, 23)

In the 1950s a number of attempts were made to break away from the crackdown implemented by Pius X, but Pius XII — ‘Hitler’s Pope’ — consolidated both the policy of censorship and the nineteenth-century declaration of papal infallibility. In an encyclical entitled ‘Of Human Nature’ he decreed that once the pope has pronounced on a topic of faith or morals, all discussion must end among theologians. This dictate was subsequently reinforced by Pope John Paul II, who proclaimed that a papal utterance precluded all further discussion on that subject. This move debarred even future papal successors from re-opening the debates in question (Cornwell, 1998, 23). These, notoriously, included issues such as the ordination of women priests, contraception, and abortion, which were the subject of four papal encyclicals in recent years. ‘Supported by this “spiritual” authority fascism and neo-fascism organized the reactionary mentality, not only of the individual, but of women, under the form of the authoritarian family. This leads to a definition of the character structure of the petit bourgeois social strata […] which from the Italy of 1922, the Germany of 1933 to the Chile of Pinochet, draw out the potential of the counter-revolution: in the Woman/mother, Woman/hearth, Woman/ Fatherland’ (Macciocchi, 1979, 74).

10Portugal under Salazar’s Concordat fully endorsed what Macciocchi, quoted earlier, called ‘fascism’s fertile mother’ (Macciocchi quoted in Caplan, 1979, 62). Not surprisingly, therefore, it enforced one of the strictest abortion laws in the Western world. Abortion was illegal and punishable with a term of prison, decriminalization applying only in the case of proven danger to the life of the mother or severe malformation of the foetus, in which case a conference of medical practitioners might decide upon an illegal but non-prosecuted abortion. In 1984, ten years after the revolution that ushered in democracy, the law was changed to legalize abortion in three specific circumstances: up to twelve weeks (and in some cases with no established upper limit) in the case of danger to the life or irreversible damage to the health of the mother; up to sixteen weeks in the case of incurable illness or malformation of the foetus; and up to twelve weeks if the pregnancy was the result of rape. In every case the abortion was to be carried out by a doctor in a recognized medical establishment. The new law, like the old one, recognized a doctor’s right to refuse to perform an abortion on grounds of conscience, and punished abortion in all other circumstances by two to eight years’ imprisonment (Comissão para a Igualdade e Para os Direitos das Mulheres/Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, 1995, 146–47).

11Some facts and figures may be pertinent here. In 1976 in Portugal, the incidence of maternal deaths per 100,000 of live births was 43.5 and the number of illegal abortions was roughly estimated at between 100,000 and 200,000 per year, abortion constituting the third most common cause of maternal deaths. By the beginning of the 90s the effects of the liberalizing abortion law of 1984 began to translate into a dramatic decrease in maternal deaths from 43.5 to 8.4 per 100,000 of live births. And in 1991 the numbers of illegal abortions were reduced from between 100,000–200,000 to between 20,000–22,000. The figures, however, continued to give cause for alarm in some quarters: in 1995 almost 8000 babies were born to teenage mothers while some figures suggested that only 30 % of women of childbearing age attended family planning clinics and only 60 % practiced contraception of any kind. For those seeking family planning advice in the late 1990s, waiting times could be as long as 8 months (Rosendo, 1998, 56–57).

12An attempt at further liberalizing the law by introducing abortion on demand up to ten weeks was rejected by Parliament at the beginning of 1997, but a motion by the JS (Juventude Socialista or Socialist Youth) and the PCP (the Portuguese Communist Party) led to its inclusion in the agenda of the following year’s Parliamentary debate. The proposed law was interpreted by many as being of an anti-punitive rather than liberalizing tendency (Ferreira, 1998, 11), and it was approved in 1998. The response on the part of the Catholic Church, centre-right factions and associated ant-abortion interests was vociferous: a referendum on the new law was immediately requested. Although under Portuguese law it is unconstitutional to hold a referendum on a law already approved by Parliament, the then Socialist government agreed to it.

13The referendum was set to take place on 28 June 1998, and debate on the matter dominated press time and newspaper column inches in the succeeding months. Public, political and religious opinion was divided, and although clearly opposed to the new law, the Catholic Church itself was undecided on the issue of whether it was feasible to hold a referendum on the right to be born, as well as on the advice to be given to the faithful on the matter of voting. The country’s bishops, for example, offered contradictory advice and injunctions that ranged from the opinion that it is impossible to hold a referendum on the right to be born, to advice on voting against the law but without the threat of excommunication, to the more extreme option of ipso facto excommunication for anyone who voted in favour of liberalization. Interestingly, Don José Policarpo, the Patriarch of Lisbon and therefore the highest prelate in the land, announced that he would not be offering advice on this matter to the faithful of his diocese. In an official pronouncement to be delivered to all parish priests, he stated that while ‘abortion under any circumstances is an attempt against life […] the stance of the Catholic Church does not incline towards criminalizing the woman’ (Policarpo, 1998, 6). Maria José Mauperrin noted that in the Sunday preceding the referendum, the tone set in masses up and down the country was divided, running the full gamut from admonitions of hellfire to absolute silence on the matter (Mauperrin, 1998, 79). The overwhelming weight of Catholic authority nonetheless urged the faithful with greater or lesser force and greater or lesser threats to vote against liberalization in the referendum.

14In the event the result was a deadlock. Only a disappointing 31.94 % of the electorate voted (2,711,712 voters), a fact some opinion writers interpreted as signalling not lack of interest but instead a vestigial (‘to be on the safe side’) fear of excommunication on the part of would-be pro-liberalization Catholic voters. Of those who voted, 49.08 % or 1,308,631 people voted in favour of liberalization. By the tiniest margin of just over one percent the no vote won, with 50.92 % (1,357,914 votes) opting against the liberalizing option. In view of the inconclusiveness of the result, it was decided to suspend the law and re-submit it to Parliament for further consideration the following year. In effect this only happened nine years later. Following another referendum on 11 February 2007 the abortion law in Portugal was liberalized on 10 April 2007, allowing the procedure to be carried out on-demand up to ten weeks, with a mandatory three-day waiting period. Abortions at later stages are allowed for specific reasons, such as risk to woman’s health, rape and other sexual crimes, or foetal malformation, with restrictions increasing gradually at twelve, sixteen and twenty-four weeks. At the instigation of the President, Aníbal Cavaco e Silva, the recommendation was enshrined in law that in all cases measures should be taken to ensure abortion was the last resort. Despite the liberalization of the laws, in practice, many doctors continue to refuse to perform abortions on grounds of conscience, which, in isolated communities where only a single doctor is available, can still make medical abortion unobtainable. One final fact may offer food for thought. In the debate leading up to the 1998 referendum, a survey of medical opinion found that a significant number of the doctors questioned indicated that even were the law to be supported by the referendum or otherwise upheld, they themselves would neither offer abortions in their hospitals or practices, nor commit funding to its implementation on demand, suggesting that considerable problems remain as regards making the law a practical reality for many Portuguese women (Rosendo, 1998, 58–64).

- 4 After the reinstatement of democracy in 1974 the Concordat was, if not officially abolished, in eff (...)

15The Carnation Revolution of 25 April 1974 had reestablished democracy in Portugal, opening the way for massive and rapid changes in women’s living and working conditions, and it specifically revised Salazar’s 1940 Concordat with the Vatican, implementing laws that protect overall freedom of worship and forbid discrimination against any religion.4 The events surrounding the referendum on abortion in 1998, however, made clear the extent to which, even a quarter of a century after the abolition of Roman Catholicism as the state religion, clerical influence and traditional attitudes concerning women and motherhood still endured in the national psyche. Politically and religiously enforced maternity was still a reality in Portugal, and Paula Rego’s Untitled (silenced) works spoke loudly about attitudes that prevailed then, and to a lesser extent still do to this day.

16Her attacks on the alliance of church and state and the undemocratic consequences of their collusion, both under Salazar and subsequently, found expression from early on. In 1981 she produced a cryptic collage and acrylic work called Annunciation (e-fig. 10) which, inasmuch as the abstract form permits interpretation, appears to depict Mary facing a mechanical set of iron pincers (either the Angel Gabriel or God himself) looming over her, ready to take possession of her consenting or non-consenting body. Religious themes returned on a regular basis in the decades that followed, including in 1997 (The Crime of Father Amaro series: figs. 3.1; 3.2; 3.4; 3.5; 3.7–3.9; 3.12; 3.14; 3.19–3.21; 3.23; 3.27) discussed in the previous chapter) and in 2002, when she produced the group of works based on episodes from the life of the Virgin Mary, to be discussed in chapter 7. Her anger at organized religion, however, reached a pitch following the 1998 referendum, and found expression in the abortion pastels of 1998–1999 (figs. 4.3–4.5; 4.14; 4.15; 4.24–4.26; 4.30; 4.31; 4.37; 4.38; 4.41; 4.49). In these, more directly even than in previous or subsequent works, she addresses herself to the enduring power of Catholicism over lives, minds, and, more to the point, politics, in post-Salazar Portugal, under what was then a Socialist government. With appalling appropriateness, at the heart of this debate lies that issue of motherhood, which, as a shared linchpin, brought together two factions — Socialism and Catholicism — otherwise antithetical in any given area of debate. Rego, having had more than one illegal abortion while an art student in London in the 1950s, identifies with the plight of working-class women in Portugal during her childhood: ‘I know what I am talking about. I know about those things. I saw the wretchedness of the women of Ericeira [in Portugal, where Rego’s family had a house]. [The pictures] are about things which we must continue to do in secret, as ever in Portugal. But it is better than not doing them!’ (Rego, quoted in Pinharanda, 1999, 3).

Life, Death and Russian Roulette

17Here is a conundrum. A gun holds six bullets. Playing Russian roulette with one bullet in the cartridge offers a one-in-six possibility of dying. Until antibiotics became widely available to combat infection in the second half of the twentieth century, an estimated one woman in every three or four, depending on the statistical source, died in childbirth. Sometimes it was worse: according to one source, for example, ‘in the French province of Lombardy in one year no single woman survived childbirth’ (Rich, 1992, 151). It follows that historically and until as recently as seventy years ago, it was safer to play Russian roulette (or to fight a war) than to give birth. And currently, given the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, the odds have been shortened again.

MEDEA — And, they tell us, we at home

Live free from danger, they go out to battle: fools!

I’d rather stand three times in the front line than bear

One child. (Euripedes, 1989, 24–25)

The implications of this for family dynamics were not negligible. Prior to the advent of contraceptives, antibiotics and routine medical hygiene, every time a woman had sex, she contemplated pregnancy and death. One woman in every three or four in the general population gestated inside her own body her potential if involuntary killer; one man in every three or four lived out the larger part of his adulthood in the consciousness of having enjoyed sexual pleasure at the price of another’s death. A significant proportion of the population lived in the awareness of having attained life at the price of that of another, and that other, their own mother. For a girl, the atonement for the involuntary matricide might lie in the subsequent surrender of life in her turn to a reproductive imperative patriarchal and patrilinear in many of its aspects. For a boy, the original unintended kin slaying became an additional factor in a complex conglomeration of psychic phenomena which together constitute the male dread and guilt of being of woman-born.

18In a text titled ‘The Hermaphrodite’ which is otherwise unsympathetic to the notion that feminism can contribute in any significant way to an understanding of female auteurship in art, Bridget Riley wrote that ‘in the act of love, physical differentiation establishes polarities which when resolved, lead in principle to the birth of a child’ (Riley, 1971, 82). Beginning from a premise whose implications almost diametrically oppose Riley’s, in one of the essays in Literature and Evil Georges Bataille argued that sexuality and reproduction, entailing as they do the transformation of the single into the multiple and the giving of one’s body to the making of an other, gesture not towards immortality but towards death as the loss of the self in its uniqueness (Bataille, 1985, 13–31). God may succeed in being both single and infinite but in the realm of the human the transition from one to many may signal dissolution (Schimmel, 1993, 13–14). Never more so, possibly, than in the multiplication act from one to two, or one to many, inherent at the heart of unwilling motherhood. By the same rationale, the patriarchal dictate of obligatory conjugal and maternal surrender to selflessness would make abortion a route (albeit a drastic one) towards the restoration of the self in its former whole (some) ness. A nineteenth-century report on ‘Observations on Some of the Causes of Infanticide’ quoted the following statement by an obstetrician:

I have known a married woman, a highly educated, and in other points of view most estimable person, when warned of the risk of miscarriage from the course of life she was pursuing, to make light of the danger, and even express the hope that such a result might follow. Every practitioner of obstetric medicine must have met with similar instances and will be prepared to believe that there is some foundation for the stories floating in society, of married ladies whenever they find themselves pregnant, habitually beginning to take exercise, on foot or on horseback, to an extent unusual at other times, and thus making themselves abort. The enormous frequency of abortions cannot be explained purely by natural causes. (Greaves, 1976, 160–61)

In the course of the analysis that follows of Paula Rego’s abortion pastels, it may be worth bearing in mind the fact that the very choice of theme offends long-standing preferences in the tradition of the visual arts in the West.

Birth has almost everywhere been celebrated in painting. The Nativity has been a symbol of gladness, not only because of its sacral significance, but because of its human meaning — ‘joy that a man is born into the world’. Abortion, in contrast, has rarely been the subject of art. Unlike other forms of death, abortion has not been seen by painters as a release, a sacrifice, or a victory. Characteristically it has stood for sterility, futility, and absurdity. (Noonan, 1976, 135)

- 5 I am grateful to Michael Brick for first suggesting this idea to me.

Abortion, then, stands not only in opposition to generic as well as specific love (for one’s sexual partner, for one’s unborn child), but in a theological — and therefore implicitly moral — sense as the exact antithesis of the initiatory and iconographic moments of the Annunciation (figs. 1.5, 4.42 and 7.2) and the Nativity (figs. 4.2, 7.3, 7.4).5

- 6 It is interesting to note that in the Gospel verse, in fact, even that joy is preceded by female su (...)

19And whereas the latter much-depicted moment gestures towards a new beginning, a world without end, abortion declares untimely closure for the child if not for the mother (for whom it might signal either death or, alternatively, the possibility of a fresh start). Be that as it may, abortion, while being the act that contravenes the ‘joy that a man is born into the world’ (John 16: 21),6 carries a significance that extends well beyond the stigma of sterility, futility or absurdity. At the secular level, the nipping in the bud of that specifically male birth interrupts the continuity of male lineages of blood, name, masculinity, property and power. And at the sacral level, it gestures towards the heresy of a contingency such that the culmination of a theological trajectory leading from God-the-Father to his divine and human progeny, is not a Sacred Son alive and immortal, but a dead foetus inside a bucketful of blood.

20The rhetoric that has situated the debate on abortion in the biblical context of holy as well as secular births, and on the sanctity of life, must also be seen as the source of these pictures by Rego, the latter gesturing as they do to Catholic intervention in a secular legislative debate. As such, in the context of the pro-choice debate, some admittedly rare pieces of antique statuary (figs. 4.1, 7.16 and 7.17) and the abortion pictures in question here all evoke three concepts excised from any biblical wish-list of desirability. First, a reinstated emphasis on the post-lapsarian labour (ious) childbirth of Eve in place of the blessed one of Mary, which ideally overrode it. Second, in the abortion images, fruitless travail with no child at the end, rather than redemptory birth. Third, and associated to the latter, the issue (meaning here both offspring and outcome) of the abortion crime (blood and gore), rather than a sacred Issue (the pure fruit of divinely anointed loins, namely a Holy Child.

Fig. 4.1 Anonymous, Statue of a childbirth handicraft from Peru (2013). Photo by Peter van der Sluijs. Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue_of_a_childbirth_handicraft_Peru.jpg

Moreover, as discussed throughout the foregoing chapters, in a Catholic context, theological concerns invariably entail political ramifications. Let us look again at Macciocchi on the subject of another European politician whose views, like Hitler’s, Salazar, found overall simpatico:

‘Coffins and cradles’ is not just one of the obsessions of Mussolini’s prose, it is also the theme of his speeches and the slogans he addressed to women. In the hysteria of an exaggerated birth-rate women were made to copulate, like rabbits, with the man-God. […] It was [Mussolini] who first launched the demographic campaign and he who dictated the first of the ten female commandments: Give Birth: ‘There is strength in numbers’. (Macciocchi, 1979, 70)

Fig. 4.2 Geertgen tot Sint Jans, The Nativity at Night (c. 1490). Oil on oak panel, 34 x 25.3 cm. National Gallery, London. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geertgen_tot_Sint_Jans,_The_Nativity_at_Night,_c_1490.jpg

Macciocchi refers to ‘the emotional plague of fascism’ that spreads through ‘an epidemic of familialism’ and sees ‘women crucified by continual procreation, as well as subjected to patriarchal authority in their capacity as mothers, wives or daughters’ (Macciocchi, 1979, 73). She depicts the collusion of interests of state, church and patriarchy under fascism, and through the operations of what she calls ‘the authoritarian family’, to the effect that ‘women belong to the community: the nation is identified with the mother, the mother with the family, and the state is an amassed heap of separate families’ (Macciocchi, 1979, 73). For Hitler in Mein Kampf, the most imperative duty of men and women was to perpetuate the (racially pure) human species.

- 7 Macciocchi’s quotations from Hitler are not referenced and have proved elusive. It has been suggest (...)

It is the nobility of this mission of the sexes which is the origin of the natural and specific gifts of providence. Our task is higher… the final goal of genuinely organic and logical evolution is the foundation of the family. It is the smallest unity, but also the most important structure of the state. (Hitler, quoted in Macciocchi, 1979, 73)7

- 8 See Duarte Vilar, ‘Abortion: The Portuguese Case’, Reproductive Health Matters 10: 19 (2002), 156–6 (...)

Not surprisingly, then, Paula Rego herself, stepping into the fray both with her 1998 abortion pastels and in a public statement following the controversy in Portugal surrounding a famous abortion trial in 2002,8 links female pain associated with the problem of illegal abortion (and, by implication in view of the legal restraints on the procedure before 2007, contemporary democratic Portugal) to a dictatorial past, which after all, it would seem, was not yet overcome:

- 9 Rego knows whereof she speaks: prior to her marriage to Victor Willing, Rego found herself pregnant (...)

The [abortion] series was born from my indignation. […] It is unbelievable that women who have an abortion should be considered criminals. It reminds me of the past. […] I cannot abide the idea of blame in relation to this act. What each woman suffers in having to do it is enough. But all this stems from Portugal’s totalitarian past, from women dressed up in aprons, baking cakes like good housewives. […] [In democratic Portugal today] there is still a subtle form of oppression. […] The question of abortion is part of all that violent context’. (Rego quoted in Marques Gastão, 2002, 40)9

The topic of abortion, therefore, sets off resonances so disturbing (and in some political contexts accusations so seditious) that they may explain the rarefaction of its translation into visual images in the history of art, past and present. When as in the images in question here, the subject is taken up and developed, its wider implications may open up other disruptive avenues of thought.

Look at Me Enjoying Myself

21In Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes that ‘men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. The surveyor of the woman in herself is male; the surveyed female. Thus, she turns herself into an object’ (Berger, 1972, 47). As has been frequently been pointed out in existing scholarship, the term erotic tends to mean erotic for men, and ‘the imagery of sexual delight or provocation has always been created about women for men’s enjoyment, by men’ (Nochlin, 1973, 9). By and for men, but also with a pedagogical intent whose target may be the other sex:

The nude in her passivity and impotence, is addressed to women as much as to men. Far from being merely an entertainment for males, the nude, as a genre, is one of many cultural phenomena that teaches women to see themselves through male eyes and in terms of dominating male interest. While it sanctions and reinforces in men the identification of virility with domination, it holds up to women self-images in which even sexual self-expression is prohibited. As ideology, the nude shapes our awareness of our deepest human instincts in terms of domination and submission so that the supremacy of the male ‘I’ prevails on that most fundamental level of experience. (Duncan, 1988, 62–63)

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Woman displayed as sexual object is the leit-motif of erotic spectacle: from pinups to strip-tease, from Ziegfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire. (Mulvey, 1975, 11)

Laura Mulvey famously elaborated on these points, with reference to scopophilia, the arousal of pleasure in cinematic viewing, in what are by now canonical essays. These writers raise a series of issues that may be pertinent in relation to Rego’s abortion pastels. First, in some of these images, as is so often the case with this artist, the import of the gaze projected out of the picture plane by its subject is equivocal. In some — though by no means all — of the images in this series, the protagonist’s gaze, if not her body, is averted from the viewer. With reference to Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at her Bath (1654, fig. 0.1), another compositionally ambiguous painting, Mieke Bal (1990, 515) maintains that the woman’s unwillingness to communicate with the viewer problematizes the latter’s moral position, as does the fabula or narrative alluded to by the picture’s theme. In a contrary move, however, in several of the abortion pastels (Untitled x, fig. 4.3; Untitled n. 5, fig. 4.4; Untitled Sketch n. 5, fig. 4.5; and even more so in Untitled Triptych b (centre panel), fig. 4.31; Hand-coloured Sketch n. 1, fig. 4.37 and Untitled Triptych c (right panel), fig. 4.38) the female protagonist looks straight back at the viewer in a manner that can only be characterized as defiant: Are you looking at me?!

22The confrontational pose, however, may echo the effect of the averted gaze in the other images in establishing the emotional rejection of the spectator. In these cases, the direct gaze emanating from the picture plane establishes a mood of active control of, rather than passive self-exposure to, the viewer. Whatever may be at stake here, viewer/voyeur pleasure is not part of the equation, or if it is, questions immediately arise regarding the moral position of the spectator as well as the possibility of sadistic pleasure. What kind of person would enjoy looking at images of abortion?

23In either case, whether the object of contemplation rejects or confronts the viewer, neither option colludes with the audience. Instead, this declaration on the part of the protagonist of, at the very least, her awareness of a voyeuristic eye focused on her, can extend to an act of defiance. This is all the more startling in view of the theme of the pictures, each of which depicts a woman either before, during or after having an abortion: in other words, a woman involved in an illegal act that ought to involve shame and guilt, but here does not. If, as Alice N. Benston would have it, viewers can be hostile to being placed in the position of the voyeur (Benston, 1988, 356), the decision to do so here neatly turns the tables as regards who has a guilty conscience and who knows it. Compositional decisions such as the posture or direction of the gaze on the part of the pictorial subject here feed into a sexual-political dimension in two ways: first, through the overturning of aesthetic conventions regarding the portrayal of gazed-upon but un-gazing female subjects, nude or not. No longer here, it would appear, are women to be seen but not seers. Second, as will be discussed at length presently, these compositional decisions have an impact through their polemical debate against social, moral and legal arguments regarding the onus of guilt on a woman (or girl: age will become an issue in this argument) who is engaged in the act of abortion.

Fig. 4.3 Paula Rego, Untitled x (1998). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.4 Paula Rego, Untitled n. 5 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

24Berger’s and Mulvey’s essays open up a wealth of questions concerning the matter of pleasure in viewing, a debate over which much ink has been spilt since, resulting in a polarization of views as to whether or not the transformative qualities of art minimize or annul the work’s ideological burden (in the case for example of female nudes, Elderfield, 1995, 7–51). At stake, among other issues, is the all-important question of a distinction, or lack of it, between high and low art, aestheticism and titillation, pleasure and perversion. A joke in dubious taste but from a distinguished provenance (attributed to George Bernard Shaw) may illustrate this point: a man asks a woman at a party to have sex with him in exchange for payment of one million pounds. After some hesitation she accepts. He changes his offer and asks her to do it for one pound. Outraged, she asks him what he takes her for. His reply: ‘Madam, we know what you are. We are just haggling about the price’. Other than the matter of market price, is there a fundamental difference between a men’s magazine centrefold on the one hand (figs. 4.6 and 4.7), and Ingres’s La Source (fig. 4.8) or Botticelli’s Venus (fig. 4.9)?

Fig. 4.5 Paula Rego, Untitled Sketch n. 5 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 60 x 42 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.6 Female body. Photo by Xmm (2005). Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_body.jpg

Fig. 4.7 Alberto Magliozzi, Manuela Arcuri (1994). Published in Playboy, special issue (2000). Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manuela_Arcuri_(1994).jpg

Fig. 4.8 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Source (1856). Oil on canvas, 163 x 80 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_Auguste_Dominique_Ingres_-_The_Spring_-_Google_Art_Project_2.jpg

Fig. 4.9 Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (1483–1485). Tempera on panel, 278.5 x 171.5 cm. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sandro_Botticelli_-_La_nascita_di_Venere_-_Google_Art_Project_-_edited.jpg

From a different slant is there a significant difference between Renoir’s pubescent girls and the standard and only slightly more titillating models of men’s magazines?

Fig. 4.10 Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Blonde Bather (1881). Oil on canvas, 82 x 66 cm. Sterling and Francine Clark Institute, Williamstown, MA, USA. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre-Auguste_Renoir_-_Baigneuse_blonde.jpg

Fig. 4.11 Alberto Magliozzi, Eva Henger Cleaning Boots (2012). Wikimedia, CC BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eva_Henger_cleaning_boots.jpg

And what distinguishes Gauguin’s famous Nevermore or Boucher’s Portrait of Louise O’Murphy from a Paula Rego uniformed school girl who happens to be in the throes of abortion pain?

Fig. 4.12 Paul Gauguin, Nevermore (1897). Oil on canvas, 50 x 116 cm. Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_Gauguin_091.jpg

Fig. 4.13 François Boucher, Portrait of Louise O’Murphy (1752). Oil on canvas, 59 x 73 cm. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fran%C3%A7ois_Boucher,_Marie-Louise_O%27Murphy_de_Boisfaily.jpg

Fig. 4.14 Paula Rego, Untitled n. 4 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

More to the point, what, if anything, differentiates the various target viewers of these images, or the nature of their pleasure? Clearly there is a difference. But there may also be a more worrying similarity, which refers to areas of ambiguous gratification, paedophilia not excluded:

The more pornographic writing [art] acquires the techniques of real literature, of real art, the more deeply subversive it is likely to be in that the more likely it is to affect the reader’s perceptions of the world. […]

A moral pornographer might use pornography as a critique of the current relations between the sexes. […] Such a pornographer would not be the enemy of women, perhaps because he might begin to penetrate to the heart of the contempt for women that distorts our culture […]. (Carter, 1987, 19–20, italics added)

Fig. 4.15 Paula Rego, Untitled n. 6 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Feminist art theory has drawn upon concepts developed in other branches of cultural theory to explore the ramifications of erotic interaction between the sexes in the visual arts. Lise Vogel, for example, uses as her starting point the well-established debate on duality in the portrayal of women in art (virgin versus whore, queen versus slave, Madonna versus Fury), which she takes to be ‘simple projections of “human” (i.e. male) fears and fantasies’ (Vogel, 1988, 46), while Carol Duncan argues along similar lines that ‘the modern art that we have learned to recognize and respond to as erotic is frequently about the power and supremacy of men over women’:

The erotic imaginations of modern male artists — the famous and the forgotten, the formal innovators and the followers — reenact in hundreds of particular variations a remarkably limited set of fantasies. Time and again, the male confronts the female nude as an adversary whose independent existence as a physical or spiritual being must be assimilated to male needs, converted to abstractions, enfeebled, or destroyed. So often do such works invite fantasies of male conquest (or fantasies that justify male domination) that the subjugation of the female will appear to be one of the primary motives of modern erotic art.

[…] The equation of female sexual experience with surrender and victimization is so familiar in what our culture designates as erotic art and so sanctioned by both popular and high cultural traditions, that one hardly stops to think it odd. (Duncan, 1988, 59–60, italics added)

Griselda Pollock contends that

[a] rt is where the meeting of the social and the subjective is rhetorically represented to us. […] What we are doing as feminists is naming those implicit connections between the most intimate and the most social, between power and the body, between sexuality and violence. Images of sexual intimidation are central to this problem and thus to a critique of canonical representation. (Pollock, 1999, 103)

And Paula Rego herself has argued that even apparently commonplace sexuality may include a dimension of violation (and therefore violence), and that in the sphere of sex ‘there are the bosses and those who obey’ (Rego quoted in Marques Gastão, 2002, 40). Following a rationale that will acquire particular relevance with regard to the abortion pastels, Duncan goes on to suggest that this project of domination includes the requirement of female pain as underwriting rather than contradicting the promise of male gratification. With reference to Michelangelo, Ingres, Courbet, Renoir, Matisse, Delacroix, Munch, Klimt, Moreau and many other old and new masters, she discusses the wealth in the visual arts of images of monstrous women, the dread of whom reflects projected male feelings of inferiority. More numerous even than these harridans, portrayed fearfully by male artists and — much less frequently, and, one suspects with different feelings — by woman artists (Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes, fig. 4.16) are their antidotes: the multitudes of blessed madonnas (Raphael, The Niccolini-Cowper Madonna, fig. 4.17), materes dolorosas (Michelangelo, Pietá, fig. 4.18) or according to Duncan, and more to the point, the suffering heroines: ‘slaves, murder victims, women in terror, under attack, betrayed, in chains, abandoned or abducted’ (Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia, fig. 4.19; Peter Paul Rubens, The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus, fig. 4.20; and Giambologna (Jean de Boulogne), The Rape of the Sabines, fig. 4.21).

Fig. 4.16 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (1611–1612). Oil on canvas, 158.8 x 125.5 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gentileschi_Artemisia_Judith_Beheading_Holofernes_Naples.jpg

Fig. 4.17 Raphael, The Niccolini-Cowper Madonna (1506). Oil on panel, 80.7 x 57.5 cm. Andrew Mellon Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grande_madonna_cowper.jpg

Fig. 4.18 Michaelangelo, Pietá (1498–1499). Marble, 230.4 x 307.2 cm. St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo%27s_Pieta_5450_cropncleaned_edit.jpg

Fig. 4.19 Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia (c. 1570). Oil on canvas, 188 x 145.1 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg

Fig. 4.20 Peter Paul Rubens, The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (c. 1618). Oil on canvas, 224 x 210.5 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peter_Paul_Rubens_-_The_Rape_of_the_Daughters_of_Leucippus.jpg

Fig. 4.21 Giambologna, The Rape of the Sabines (1583). Marble, 106.4 x 160 cm. Piazza della Signoria, Florence (south view). Wikimedia, CC BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Firenze_-_Florence_-_Piazza_della_Signoria_-_View_South_on_The_Rape_of_the_Sabine_Women_1583_by_Giambologna.jpg

Their pain becomes the warranty of the ability of the opposite sex to subject them to control. I should wish to argue that the idealization of variously suffering women who are the victims, handmaidens or, more crucially, mothers of a series of lordly males is not devoid of complexity, since for a woman to be a mother she must either be the Virgin Mary or she must have had sex like Eve, and suffer for it. In other words she must be either not really a woman but rather ‘young, her body hairless, her flesh buoyant, [devoid of] a sexual organ’ (Greer, 1985, 57) — in short, both virginal and infantilized — or alternatively she must be a whore, and if so, both visible and punishable as such. And since, as we know, with one single exception women cannot be both virgins and mothers, a mother (Eve) must also by definition be always part-whore.

The Image as Problem Child

25Other instances of the adumbration of what, technically, are mutually exclusive categories of representation, offer viewers-against-the-grain a welcoming foothold. Feminist art criticism has debated the conflation of, for example, the two separate genres of pregnancy and nudity by artists such as Paula Modersohn Becker and Käthe Kollkwitz (Betterton, 1996). If, as Betterton would have it, ‘ [f] or both artists, the “maternal nude” was one means by which they could address issues of their own sexual and creative identity at a time when the roles of artist and mother were viewed as irreconcilable’ (Betterton, 1976, 175), an analogous process of counter-intuitive category pairings might be said to be at work in Paula Rego’s gallery of fully-clothed, mock-erotic abortion girls. Trouble begins to arise in this neatly dichotomous painterly paradise of maidens and sluts when, as is the case with the Rego abortion pictures, the woman who clearly lapsed and sinned, and who moreover is about to compound that sin of fornication with the crime of abortion, carries not the accoutrements of the whore but rather all the hallmarks of the coltish or half-grown, newly-fledged girl-child (n. 4, fig. 4.14), sometimes still wearing her school uniform (n. 6, fig. 4.15).

Watching Him Watching Her: Everything Depends on the Eye of the Beholder

26Susan Glaspell’s now canonic short story, ‘A Jury of Her Peers’ (1917) offers us a tale about the different views of a crime scene when viewed by women and by men. Where the men see nothing of relevance in the house of a man found murdered, the women pick up the markers of conjugal cruelty that might have led the wife to kill her husband: the dilapidated house, the threadbare clothes, a piece of sewing in which the stitching suddenly becomes irregular, and above all the corpse of a song bird whose neck had been wrung.

Martha Hale sprang up, her hands tight together, looking at that other woman, with whom it rested. At first she could not see her eyes, for the sheriff’s wife had not turned back since she turned away at that suggestion of being married to the law. But now Mrs. Hale made her turn back. Her eyes made her turn back. Slowly, unwillingly, Mrs. Peters turned her head until her eyes met the eyes of the other woman. There was a moment when they held each other in a steady, burning look in which there was no evasion or flinching. Then Martha Hale’s eyes pointed the way to the basket in which was hidden the thing that would make certain the conviction of the other woman--that woman who was not there and yet who had been there wit them all through that hour. (Glaspell, 1917, online)

If the production of art has traditionally presupposed the presence of a male viewer and the requirement of male gratification, Paula Rego turns the tables on that tradition in a variety of ways. For example, by addressing herself to an implied female audience, as much of her work has been supposed to do, she may be playing precisely on those two time-honoured assumptions: first, an implied male gaze, and second, one that, following Duncan, is gratified by these scenes of female pain. Speaking with a forked tongue, she may knowingly be tempting an unwary male appetite for the female body while exposing it to the eyes of women watching him watching them. The attempted resolution of these two matters gains complexity, furthermore, as one considers the nature, posture and identity of the female models. As regards posture, a cursory glance suggest that pictures such as for example n. 3 (fig. 4.24), and n. 7 (fig. 4.25) and the left-hand panel of the triptych (fig. 4.26) reproduce the standard reclining posture of any number of eroticized female figures throughout centuries of visual art production (George Breitner, Anne, Lying Naked on a Yellow Cloth, fig. 4.22; Ingres, Large Odalysque, fig. 4.23; Gaugin, Nevermore, fig. 4.12).

Fig. 4.22 George Breitner, Anne, Lying Naked on a Yellow Cloth (c. 1888). Oil on canvas, 95 x 145 cm. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Wikimedia, public domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Breitner_-_Reclining_Nude.jpg

Fig. 4.23 Pierre-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Grand Odalisque (1814). Oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm. The Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ingre,_Grande_Odalisque.jpg

Fig. 4.24 Paula Rego, Untitled n. 3 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.25 Paula Rego, Untitled n. 7 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.26 Paula Rego, Untitled Triptych (left-hand panel) (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

In fact, however, a closer look renders this initial impression and the reflex of erotic response problematic: Rego’s models are not necessarily women but rather sometimes girls (children); their posture is not one of sensual invitation but acute suffering and these are depictions not of pleasure but of pain. And who gets pleasure from the pain of another? Some do, of course. There is a name for that.

27In the case of the abortion images, spectator gratification is partially blocked from the start by the absence of nudity. But more crucially, pleasure — the male viewer’s — and pain — the girlish models’ — (or, to put it differently, cause and effect) become dangerously indistinct, suggesting two things: first, the foregrounding of a fact that has habitually been a moral imperative, and that canonical art traditionally presupposes whilst euphemistically sweeping it under the carpet: namely that for women, sexual delight potentially carries a sting in the tail and may have to be purchased at a high price; and second, the fact that for the male viewer, that pain may be part of the point and may underpin the pleasure. But again, who would admit to such tastes?

28Nobody? As a matter of fact, a brief wander through any museum or art collection (not to mention the magazines on the top shelf in newsagents or, in the last few decades, the internet) suggests that plenty would and do indulge it, openly, for more or less money, and for a variety of reasons which may or may not include the pleasures of coercion and unrestrained power. The blurring of categories of pain and pleasure, both in Rego’s pictures and in well-known images in the art canon (n. 7, fig. 4.25 and sketch 3, fig. 4.30 in relation to Modigliani, Reclining Nude, fig. 4.27), draws attention to potential ambivalences of other kinds, such as for example the process whereby the categories of childbirth (consecrated) and abortion (condemned) become indistinguishable (W. Gajir, fig. 4.28). So much so that it is no longer possible to draw a line between on the one hand the hallowed maternal anguish of mater dolorosas and pietàs regarding sons both born and unborn (Juan de Valdés Leal, Pietà, fig. 4.29) and on the other a crime atoned for with sorrow (Untitled n. 4, fig. 4.14; Untitled n. 6, fig. 4.15); between perpetuity (life) and closure (termination of life); or between fruitful and fruitless labour.

Fig. 4.27 Amedeo Modigliani, Reclining Nude (1917). Oil on canvas, 60.6 x 91.7 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Wikimedia, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1917_Modigliani_Reclining_nude_anagoria.JPG

Fig. 4.28 W. Gajir, Sculpture of Childbirth (n.d.), Mas, Bali. Photo by Kattiel. Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bevalling_Bali.jpg

Fig. 4.29 Juan de Valdés Leal, Pietá (late 17th century). Drawing, 17.6 x 23.5 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_Piedad_(Vald%C3%A9s_Leal).jpg

Fig. 4.30 Paula Rego, Untitled Sketch n. 3 (1998). Pencil on paper, 31 x 42 cm. Artist’s collection. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

I would argue that in these images such distinctions are kept deliberately ambivalent and therefore enduringly preoccupying. Were it not for the conspicuous absence of babies in Rego’s abortion images, the referents for some of these pictures could be straightforward scenes of childbirth or somewhat graphic nativities (Untitled Triptych b, fig. 4.31; Hand-Coloured Sketch, fig. 4.37).

29Alternatively, some might also be mistaken for representations of invitation to male penetration or self-pleasuring (Untitled Sketch 3, fig. 4.30).

30Here, however, they refer instead to female anguish without fruit and possibly also to sexual coercion of various kinds (rape, abuse, incest, abusive sexual relations between grown men and young girls), all giving rise to unwanted pregnancies. They may signal, furthermore, male pleasure derived at the price of anguish (the sexual act that led to the pregnancy) as well as from the contemplation of the experience of anguish itself (as depicted in its visual representation). Angela Carter gave us the term ‘moral pornography’ for material that, albeit conventionally pornographic, might, by its very nature, render explicit certain aspects of pleasure exacted at the price of pain within the arena of gender conflict:

The sexual act in pornography exists as a metaphor for what people do to one another, often in the cruellest sense […]. And all such literature has the potential to force the reader to assess his relation to his own sexuality, which is to say to his own primary being, through the mediation of the image or the text. This is true for women also, perhaps especially so, as soon as we realize the way pornography reinforces the archetypes of her negativity and that it does so simply because most pornography remains in the service of the status quo. […] It is fair to say that, when pornography serves […] to reinforce the prevailing system of values and ideas in a given society, it is tolerated; and when it does not, it is banned. […] When pornography abandons its quality of existential solitude and moves out of the kitsch area of timeless, placeless fantasy and into the real world, then it loses its function of safety valve. It begins to comment on real relations in the real world. […] And that is because sexual relations between men and women always render explicit the nature of social relations in the society in which they take place and, if described explicitly, will form a critique of those relations. (Carter, 1987, 17–20, italics added)

Fig. 4.31 Paula Rego, Untitled Triptych b (centre panel) (1998). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

- 10 Morrison, Blake, Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper (London: Chatto & Windus, 1987), 23–36.

Paula Rego’s pictures, both in this series and previously, draw upon some of the concepts outlined by Carter above, by foregrounding the insidious aspect of pain at the heart of the pleasure principle, or the inextricability of the two, at stake in canonical art. And her sources, too, uneasily conflate love and desire with hate and anger, for example in Moth (fig. 4.32) based on Blake Morrison’s poem of the same title, in which love-making turns into revenge sex.10

This chip of cedarwood

with the linsey-woolsey face

is furred like the ermine

it stole inside one Christmas

while she lay, splay-winged,

beneath my weight.

Our last hunt ball

before the child came!

She’d been a tease that night,

fluttering round Molphey

and the colonel: this curt fuck

was how I paid her back. (Morrison, 1987, 37–38)

Like Angela Carter, Blake Morrison, a poet admired by Paula Rego, understood the darkness that sometimes lies beneath seemingly orthodox relations between men and women. In another poem, ‘Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper’, he speaks chillingly of a phenomenon that Joan Smith, a writer and journalist assigned to the case of Peter Sutcliffe’s serial killings in the 1970s and 80s also ponders: the possibility that, as regarded their attitudes to women, the difference between Sutcliffe, the policemen who were trying to catch him and indeed the average man on the proverbial Clapham Bus, might have been negligible:

Ah’ve felt it in misen, like,

Ikin ome part-fresh

Ower limestone outcrops

Like knuckles white through flesh:

Ow men clap down on women

T’old em there for good

An soak up all their softness

An lounder em wi blood.

It’s then I think on t’Ripper

An what e did an why,

An ow mi mates ate women,

An ow Pete med em die.

I love em for misen, like,

Their skimmerin lips an eyes,

Their ankles light as jinnyspins,

Their seggy whisps an sighs,

Their braided locks like catkins,

An t’curlies glashy black,

The peepin o their linnet tongues,

Their way o cheekin back.

An ah look on em as equals.

But mates all say they’re not,

That men must have t’owerance

Or world will go to rot. (Morrison, 1987, 23–36, italics added)

In The Sadeian Woman Angela Carter argues that the violence that underpins pornography is quantitatively rather than qualitatively different to normal sexual relations, just as Vikki Bell maintains that paedophilia (for instance between an older man and his young relative) plays on a distortion of the view that the young should obey and feel love (philia) towards their elders. Corrupt family bonds will be discussed in the analysis of fairy tales and nursery rhymes in chapter 6. Regarding the series of abortion images under scrutiny here, likewise, what we face are travesties as well as sometimes simply straightforward exaggerations of a variety of standard iconographic poses and compositions (annunciations, nativities, reclining nudes, sexual frolics), which as such set off a tripartite reaction.

31First, they lure the gaze into a mood of expectant gratification (as encouraged by the superficial similarity between these images and standard reclining lovelies such as Thomas Rowlandson’s Sleeping Woman Watched by a Man (fig. 4.33), Ingres’ Large Odalysque (fig. 4.23), Gaugin’s Nevermore (fig. 4.12), Boucher’s Portrait of Louise O’Murphy (fig. 4.13) or almost any renowned painter of the female figure down the centuries.

Fig. 4.32 Paula Rego, Moth (1994). Pastel on canvas, 160 x 120 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.33 Thomas Rowlandson, Sleeping Woman Watched by a Man (n.d.). Watercolour with pen and grey ink on paper, 13.1 x 19.7 cm. Yale Centre for British Art. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Rowlandson_-_Sleeping_Woman_Watched_by_a_Man_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Second, and contrarily, the appeal becomes quickly mingled with the shock of realization that goes hand in hand with a dawning awareness of the subject matter involved. Together with this comes the awareness that without a title, an image depicting abortion is indistinguishable from one depicting the ecstasies of love (Love, fig. 4.34), or the delight of a bride (Bride, fig. 4.35).

32Third, and perversely, it is possible that the afterthought of quasi-Aristotelian fear and pity that follows the understanding of what we are looking at (which technically ought to lead to the purification of catharsis, Aristotle, 1985, 49–51), in its turn may give way to the titillation and frisson of perverse and perverted pleasure originating in someone else’s pain.

33And finally, this pleasure in its turn may trigger the reflex moral questioning of one’s viewer position, and of the nature of pleasure to be derived from much canonical art, an important component of which has traditionally been pain, and the master-slave relationship between male viewer and female object.

Fig. 4.34 Paula Rego, Love (1995). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 120 x 160 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.35 Paula Rego, Bride (1994). Pastel on canvas, 120 x 160 cm. Tate, London. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

A Target of Indifference

34Indifference to, or non-recognition of an established power structure, combined with careless provocation (sexual and otherwise), has always been an element that goes beyond irreverence in Paula Rego’s art (Target, fig. 4.36). Do it to me if you dare.

35In Target, obliviousness or provocation in the face of danger to self, or bravado regarding the desecration of the established rules of others (as illustrated by the unwillingness to communicate with the viewer, discussed earlier) carries further implications. In the abortion pastels, what is largely at stake on the part of the girl protagonists appears to be an unsettling awareness of, yet indifference and/or hostility to, the viewer (n. 1 sketch n. 1, fig. 4.37, tryptich c, fig. 4.38).

Fig. 4.36 Paula Rego, Target (1995). Pastel on canvas, 160 x 120 cm. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.37 Paula Rego, Hand-Coloured Sketch n. 1 (1998). Pencil on paper mounted on aluminium, 31 x 42 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

Fig. 4.38 Paula Rego, Untitled Triptych c (right panel) (1998). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm. Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved.

In another context Alice N. Benston identifies an intent on the part of certain artists to appeal ‘to male anxiety, since any insistently female world implies the avoidance or even the need for a male presence’ (Benston, 1988, 356) It is a commonplace of human relations that indifference may be more unsettling than enmity. And therefore the absence of a child (through expulsion from the womb) acquires further relevance in the context of male anxieties about masculine dispensability. According to Freud the child represented a substitute phallus that soothed a woman’s penis envy and castration complex. If so, it follows that the voluntary termination of pregnancy conveys a lack of interest in or refusal to acknowledge the significance of the male organ and its symbolic association with gender power. Thus, the act that refuses the male his progeny contests also the former’s existential relevance. Some of Paula Rego’s protagonists, by virtue of their deliberate indifference (looking at the viewer without seemingly registering his presence as being in any way significant), may work to create the effect identified by Benston: namely hostility on the part of the male viewer at being put in the voyeur’s position; and anxiety, ‘since this insistently female world implies the avoidance or even the irrelevance of a male presence’ (Benston, 1988, 356). The Holy Ghost (the über-impregnator and intangible representative of all fathers in the masculinist master narrative of engendering) now becomes the inconsequential — literally ghostly — spectator of these rogue nativities. Even if, while being treated as negligible, it and men in general remain simultaneously and paradoxically implicated in the sin or crime at hand. More of this later.

36Be that as it may, the effect of Paula Rego’s pictures is to foreground the process whereby what draws the implied male gaze is also that which places its owner (and the art tradition from which he hails, and which has trained him in that gaze), morally in a very dubious position. This is so because it may be true that the difference between the languid but fully-grown beauties or even the winsome and playful children of the art canon on the one hand, and its raped damsels or these Regoesque little girls in pain on the other, is quantitative rather than qualitative.

37Clearly there is nothing more innocent (or is there?) than the pleasure given and received from the contemplation of a Renoir child or a Heyerdahl picture of childish innocence (figs. 4.39, Renoir, Girl with Hoop and 4.40, Heyerdahl, Little Girl on the Beach).

38Less clearly, what kind of man or citizen or moral being would be the implied male viewer sexually and aesthetically gratified by the pain of pregnant school-age girls forced into clandestine abortions? A sadist? A paedophile? An alter ego of the impregnator of pre-age-of-consent school girls such as those featured in Untitled n. 4 (fig. 4.14) or Untitled n. 6 (fig. 4.15)?

- 11 It may be interesting to bear in mind, in this context, that if the term ‘virgin’ means, as some sc (...)

39The implied threat of female sexuality, let alone a deviant one (because, as here, infantine), is therefore overshadowed in the pictures by two other factors: first, the implications of male sexual behaviour that results in the pregnancies of little girls and adolescents; and second, the moral ramifications of a viewing behaviour that delights in the contemplation of these disturbing child-brides11 and does not acknowledge responsibility for the bloody aftermath of their seduction. In Rego’s abortion images there is no man present to lend support. The father is as invisible as any ghost, Holy or otherwise.

Fig. 4.39 Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girl with Hoop (1885). Oil on canvas, 125.7 x 76.6 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Girl_with_a_hoop.jpg

Fig. 4.40 Hans Olaf Heyerdahl, Little Girl on the Beach (n.d.). Oil on canvas, 60 x 45 cm. Private collection, Wikimedia, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hans_Olaf_Heyerdahl_-_Little_girl_on_the_beach.jpg

Child Brides

40In its early formulations, feminist art theory trod much the same path as other areas of feminist cultural theory. For Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, for example, ‘a radical feminist art would include an understanding of how women are constituted through social practices in culture’:

Once it is understood how women are consumed in this society it would be possible to create an aesthetics designed to subvert the consumption of women, thus avoiding the pitfalls of a politically progressive art which depicts women in the same forms as the dominant culture. (Barry and Flitterman-Lewis, 1988, 88)

- 12 Nathanson, Bernard, The Silent Scream (1984), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Hb3DFELq4Y