Image, Knife, and Gluepot

|3. The Beghards in the Sixteenth Century

Texte intégral

- 1 As David S. Areford shows in The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe, Visual Cultu (...)

One day in 2006 when I had called up the print of St Mark (643, see fig. 37) in the BM’s paper mine, another rich vein presented itself. I worked this vein in the same sessions as pursuing the mother lode of Add. 24332. In the nineteenth century, curators mounted duplicate prints from the same matrix onto the same matte, side by side, so that they could be compared. After all, Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945) — the art historian who had pioneered the use of dual projectors in classrooms, so that related images could mutually emphasise each other’s similarities and differences — had shaped how the study of images would be taught. This had far-reaching consequences for how they would be stored and displayed, too. An example was the matte I had before me. Stuck to it was a print accessioned on 9 November 1861 from the beghards’ manuscript. It depicted St Mark but contained signs that a beghard had tampered with it: he had added what looked like a red kiosk to the otherwise empty area on the horizon line. This refashioned print of St Mark appeared on the matte with its twin, a print made from the same plate. This other print, which had been accessioned on 14 November 1868, had been treated differently. It had no extra lion stuck to it, no red penwork frame, and was instead painted with colour washes.1 What route had this print followed to land in the museum? It was time to return to the Register — the great handwritten ledger in which curators had inscribed new acquisitions in the nineteenth century — this time for the volume dated 1868.

1Tracing this print to its original manuscript took me on a journey that led back to Maastricht, once again. St Mark came from a manuscript that provides a snapshot of the beghards 25 years later and provides insights into how they changed over that period. The beghards’ early experiment with prints around 1500 had blossomed into a mania by 1525. They also developed their initial calendar-cum-table of contents and systematized it in the later book. I argued earlier that the beghards were interested in prints because prints allowed them to produce highly illustrated manuscripts with little skill. But this later example demonstrates another reason why they were enamoured of prints: they allowed the beghards to keep up with a quickly changing, image-centred devotional culture.

Another Hoard of Prints From Maastricht

- 2 In fact there were more than 231 prints entered on this day; the conservators deliberately skipped (...)

According to the Register, 231 early prints entered the collection on 14 November 1868, with the accession numbers 1868,1114.1–231.2 They were all purchased in a single lot from a certain Mr Drugulin. In the Register, in another hand, a note was scrawled: ‘See Naumann’s Archiv, 1868.1’. When the British Library physically split off from the British Museum in 1997, most of the reference books went to the new building — the library — so it would be a while before I could figure out what Naumann’s Archiv was and peruse it, but for the moment I studied the Register and started calling up groups of the 231 prints.

2As I ordered about five prints at a time, dismembered manuscript pages glued to mattes emerged from boxes. Working through a few boxes of prints immediately revealed that the prints accessioned on 14 November 1868 had come from a single manuscript. About two thirds of the prints had been peeled off their manuscript supports, and the other third were still mounted on the folios of the manuscript. For example, a print depicting the Virgin of the Sun was mounted on a disgorged manuscript leaf as in e-fig. 67.

BM 1868,1114.196 — Virgin in sole, engraving pasted to the leaf of a prayerbook (e-fig. 67)

Virgin in sole, engraving pasted to the leaf of a prayerbook. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.196.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/fc2487da

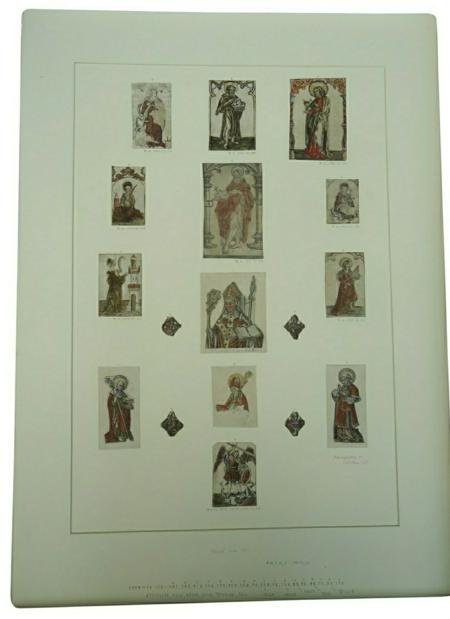

These folios once again had the strange and distinctive feature of being foliated. So overwhelmed was the person charged with mounting the prints in 1868 that he simply organized them thematically, by subject, not bothering to divide them by ‘hand’ or school. For example, one matte brandished a fistful of folios from the manuscript, all with Christological themes (fig. 93). Another matte turned up seventeen ‘trimmed and silhouetted saints’ from the manuscript (fig. 94).

Fig. 93 Matte from 1868, with Christological prints removed from Add. 31002. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings.

Fig. 94 ‘Trimmed and silhouetted saints’ affixed to a matte assembled in 1868. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings.

- 3 The Koninklijke Bibliotheek — The National Library of The Netherlands — purchased the album in 1900 (...)

As is clear from the designs made by gluing print fragments onto archival mattes, the motivations went beyond the desire to join like with like. Another urge was to create sympathetic, symmetrical designs by rearranging curios from the past, including manuscript illumination. For example, a nineteenth-century collector, possibly in England, applied knife and glue to several manuscripts, including a Bolognese liturgical manuscript from the early fourteenth century. She or he excised the Latin script from the page and reorganized the silhouetted miniatures and disembodied pieces of acanthus into surreal designs, pasting them onto the clean, inviting pages of a modern album (e-fig. 68).3

3Devoid of walls of Latin script, initials, and frames, the figures have been reduced to abstract forms of painted parchment. A kneeling saint praying to a giant bird flying overhead typifies the absurdist compositions and the jolting variations in scale. The album maker exercised other principles: that the composition should be as symmetrical as the elements allowed, and that each element should have maximum space around it, with no overlapping. Another composition reveals that at least two manuscripts donated their vital organs to make this compilation (e-fig. 69).

Folio from an album with manuscript cuttings (e-fig. 68)

Folio from an album with manuscript cuttings. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 131 F 19, fol. 10r.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/31a0dbf8

Folio from an album with manuscript cuttings (e-fig. 69)

Folio from an album with manuscript cuttings. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 131 F 19, fol. 12r.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b3b64d40

- 4 On the topic of Grangerization, I have benefitted from conversations with my former undergraduate s (...)

The composer has decided to top and tail the main narrative — about the massacre of a group of clerics — with acanthus clipped out of books from two periods. The page therefore reveals further principles of design: to cut down the illuminations to the quick, even when that means expelling visual data essential for meaning-making, and to offer visual variety. These practices were popular among collectors even before the nineteenth century. In 1769 James Granger started cutting up books to liberate images to paste in other books, a process later called Grangerization.4 The practices of collectors reflected the practices of museum curators.

4An enormous and densely illustrated prayerbook must have undergone extreme vivisection to yield this quantity of printed relics. All the prints in the group had been hand-coloured in the same palette, consisting of washes in muted red, green, and yellow. Typical are the washes that appear on an engraving by the Monogrammist MB depicting the Nativity (e-fig. 70).

BM 1868,1114.210 — Folio of the beghards’ later book of hours (e-fig. 70)

Folio of the beghards’ later book of hours, with an engraving depicting the Nativity attributed to Monogrammist MB. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.210.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/73f718b0

Colours have been applied to the brick wall to give it a relentless pattern and dizzying recession. Moreover, the painter has added a decorative border to nearly all the prints. These borders consist of red-brown pen and ink and wash. Their chromatic consistency suggests that the person who applied the colour to the prints may have been the same person who added this decoration. It seemed likely, therefore, that the person or persons who wrote and decorated the manuscript purchased the prints in black and white and then coloured them systematically. This stands in contrast to the situation with Add. 24332, in which most of the prints were either left in black and white or purchased already coloured. This suggests that in the intervening 25 years printers had stopped marketing hand-coloured prints, or stopped trying to make them look like miniatures, or that the public had become used to black and white prints and were ready to accept them as they were, without the extra colouring. The owner of these prints was able to turn their dullness into a virtue by giving them a common look.

- 5 Robert Priebsch, Deutsche Handschriften in England, 2 vols (Erlangen: Fr. Junge, 1896–1901).

5Like Add. 24332, the host manuscript for this new cache of prints was a prayerbook written in an eastern dialect of Middle Dutch. I wondered whether the parent manuscript was also in the British Library. Rather than using the Bibliotheca Neerlandica Manuscripta as a guide to continue to work through every Netherlandish manuscript in the BL in numerical order, a plan that I reckoned would take about ten years, I took a shortcut, namely, scouring Priebsch’s catalogue of the Dutch- and German-language manuscripts of what had been the British Museum at the time when he was writing, in 1896–1901.5 Priebsch notes the provenance of each manuscript and describes several as having been ‘Transferred from the Dept of Prints and Drawings’. I made a list of these transferred and called them all up the next time I could get to the British Library, which was 26 April 2006. One of those on my list was Add. Ms. 31002, a thin volume with the calendar and the ragged, mangled, stripped-down pages of a once richly decorated book of hours. The book was emaciated because much of its bulk had been sliced off and accessioned into the BM’s Department of Prints and Drawings in November 1868.

Fig. 95 Folio in the beghards’ later book of hours, with Virgin of the Sun standing on the moon (added engraving), c. 1525. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fol. 138r.

There was a single print left in the volume, showing the Virgin of the Sun (fol. 138, fig. 95). It provided an indication of what at least half the incipits would have looked like. According to a note on the second paper flyleaf, the manuscript was ‘Transferred from the Dept of Prints and Drawings 24 March 1879’. I had uprooted another broken manuscript and was already well on my way to reconstructing it. That first day I got a feel for the book and started transcribing the calendar.

6Putting this book together would again be aided by a late medieval organisational system — foliation. Like the loose leaves preserved in the British Museum, the leaves in this manuscript have the folio numbers written in large numerals at the top of every recto. The scribe who wrote them must have seen the advantages of Arabic numerals over Roman, cognitively, mathematically, and spatially. Not only did he inscribe them at a scale commensurate with the large letters in the text block, but he further called attention to their presence by decorating them: the numbers often appeared in a nest of penwork. Some numbers appeared in decorative frames, such as the number 235 (e-fig. 72), where the scribe/illuminator responded to the bulbous fruit form inside the frame and extended that shape with festooning penwork into the margin.

7On other pages, ornate manicules point to the numbers. For their maker and early users, these numerals framed the modern system organising the book. For me, these numbers would help to connect the loose sheets to the body of the book in their original sequence. I realised very quickly that the prints’ accession numbers corresponded to their position in the manuscript, Add. 31002. In other words, their accession numbers correspond to the order in which they were removed from the manuscript, which was systematic, from the beginning of the manuscript to its end. That is one reason I decided not to make a spreadsheet to reconstruct the manuscript, since to do so was uninteresting as a puzzle, but only a simple task and that requires zipping the removed prints and folios up with the bound folios in Add. 31002. Their accession numbers fall in the same sequence as the folio numbers of the manuscript.

8Recontextualizing the prints reveals that the makers adjusted some of them before inserting them. For example, they silhouetted an engraving depicting a bishop wearing a mitre.

BM 1868,1114.115 — Bishop wearing a mitre (e-fig. 66)

Bishop wearing a mitre. Hand-painted engraving, trimmed and silhouetted. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.115.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/cc55a7af

This print was lifted from fol. 272 (now Add. 31002, Part 2, modern fol. 62) (fig. 96), a folio with an elaborate penwork frame that must have originally snuggled around the print, some red strokes of which are still visible on the fragment. The scribe was interpreting the print as a St Lambert, because only the top of the print was used: the head and the attribute were cut off. This print may have originally depicted a different bishop, but, as the beghards did in 1500, they could creatively trim inconvenient details from prints in order to adjust their identities.

Fig. 96 Folio in the beghards’ later book of hours, c. 1525, from which an engraving depicting a bishop’s upper body was removed in 1868. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. II, 62r (original fol. 272).

The Calendar of Add. 31002

In 2006 I was not, in fact, seeing this manuscript for the first time; I had seen it a few years earlier, before I started systematically dating my notes. However, at that time, I had rejected it for the project I had been working on, but puzzled over its unusual calendar with its extra row of numbers. I had not suspected that the numbers referred to folios within that particular prayerbook, that it formed an internal indexing system. I did not have the lenses to see the extraordinary features in the manuscript until I saw it for the second time. That is typical of my experience with primary evidence. I need to study it, reflect on it, and return to it months or years later before I can grasp its working even partially. Funding councils never understand this: it takes multiple trips to Paris, London, Maastricht, and elsewhere to work out such relationships.

9When I began working on Add. 31002 in earnest, in 2006, the prints in the BM with the accession numbers 1868,1114.1–231 had not yet been scanned. This made it extremely difficult to work on them since they were available for only a few hours a day, on the opposite side of the English Channel from where I lived. I directed my attention instead to the manuscript from which they had come, Add. 31002. But even that took a long time. Because professional photography was prohibitively expensive, and hand-held photography was not permitted in the manuscript reading room at the British Library then, I had to work on the manuscript in the flesh. A little more than a year passed before I could return to the BL to transcribe the whole calendar, on 17 May 2007. When I did so, I learned that the calendar has an extraordinary number of feasts for the translations of saints local to the eastern Netherlands, as well as many Franciscan feasts. Specifically:

|

April |

28 |

Translation of St Lambert, bishop of Maastricht (272) |

|

May |

13 |

St Servaas, bishop of Tongeren, whose relics are in Maastricht (283) |

|

25 |

Translation of St Francis (285) |

|

|

30 |

Translation of St Hubert (287) |

|

|

June |

7 |

Translation of St Servaas (283) |

|

13 |

Translation of St Bartholomew (332) |

|

|

21 |

Martin, bishop of Tongeren |

|

|

July |

31 |

Translation of the 11,000 Virgins (360) |

|

Aug. |

5 |

Translation of St Ghielis [aka Gilles] (338) |

|

11 |

Translation of St Trudo (384) |

|

|

12 |

Clara virgin (323) |

|

|

Sept. |

1 |

Ghielis abbot (338) and Translation of St Mathias (258) |

|

9 |

Feast of the Dedication of the Church (no folio number) |

|

|

16 |

Five Wounds of St Francis (343) |

|

|

17 |

Lambert bishop and martyr (345) |

|

|

29 |

Michael archangel (350) |

|

|

Oct. |

3 |

Translation of St Clara (323) |

|

4 |

Francis confessor (355) |

|

|

11 |

Gummarus knight (venerated in Lier; no folio number) |

|

|

13 |

Lambrecht’s victory (venerated only in the diocese of Luik; 345) |

|

|

22 |

Severus bishop (361) |

|

|

Nov. |

3 |

Hubert bishop (371) |

|

23 |

Trudo abbot and confessor (384) |

|

|

Dec. |

9 |

Translation of St Bartholomew (332) |

As these feasts indicate, the calendar emphasises Franciscan saints (Francis, Clara, Trudo), saints venerated in the diocese of Liège and in Maastricht in particular (St Lambert was the bishop of Maastricht and St Servaas was the bishop of Tongeren and Maastricht; fig 97 and 98). I pored over lists of pre-Reformation monastic houses by region and by rule affiliation. Was it possible that Add. 31002, like Add. 24332, had been produced in Maastricht by the beghards of St Michael and St Bartholomew? Indeed, Michael and Bartholomew are also featured in the calendar; the problem was that these two were widely venerated and therefore featured in nearly every calendar. It is much easier to use calendrical data to localise a manuscript to a church dedicated to some obscure saint, venerated in only one minuscule church, and written in gold with maybe an extra prayer dedicated to that saint, which is also singled out with special decoration. The calendar in 31002 did not provide proof enough. And it differed significantly from that in 24332. I baulked at the thought that the two manuscripts had come from the same place because, frankly, they hardly resembled each other.

10Moreover, the calendar of Add. 31002 has some entries that make it clear that the later manuscript was not a copy of the earlier one, and it may have been made for a different community. Firstly, whereas the earlier manuscript has some blanks in the calendar, there are none in the later manuscript. Secondly, Add. 31002 has the feast of the church consecration on 10 September, a feast which is lacking in Add. 24332. I wondered, therefore, whether the later manuscript could have been made by different male Franciscans in the diocese of Luik, who had borrowed Add. 24332 as a model. A further problem with the indexing system is that the folio numbers referred to items that were not actually in the book, which had only 197 folios. Could it be that the index pointed to another book altogether? If so, then the organisational system in Add. 31002 was even more complex than that in Add. 24332.

Fig. 97 Opening from the calendar of the beghards’ later book of hours for August-September. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fols 8v-9r.

Fig. 98 Opening from the calendar of the beghards’ later book of hours for September-October. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fols 9v-10r.

11In the meantime, I finally tracked down an article by A. Andresen in the Archiv für zeichnenden Künste, edited by Robert Naumann and published in Leipzig in 1868. (Years later, it is now digitized and available online.) This volume is referred to as Naumann’s Archiv in the literature, and abbreviated N.A. in the documents of the BM, including the mounts to which the prints with accession numbers 1868,1114.1–231 are pasted. The article begins (in my translation from the German):

- 6 A. Andresen, ‘Beiträge zur älteren Niederdeutschen Kupferstichkunde des 15. und 16. Jahrhunders’, A (...)

Mr Drugulin the art dealer has recently acquired a Low German prayerbook from the first half of the sixteenth century, which is rich with images and deserves its own study. Any friend of old copper engravings should be especially interested in the contents, because nearly all the leaves it contains are unknown and do not appear in Bartsch or Passavant.6

Andresen’s article was published in 1868, the same year that the BM acquired the manuscript and accessioned the prints (on 14 November). Wilhelm Eduard Drugulin (d. 1879) was an art dealer in Leipzig who specialised in prints and drawings. When Andresen studied the manuscript shortly before 1868, the prints were still affixed to the leaves of the intact manuscript.

12Attributing the manuscript to the convent at St Trond, Andresen writes:

- 7 Ibid., p. 1.

One can assume with great likelihood that this prayerbook originated with a monk in the monastery of St Trond in Liège. The library in Liège preserves a number of manuscripts from this above-named convent, and another from ‘Frater Truda Gemblacensis’ decorated with 58 prints belongs to T. O. Weigel in Leipzig. The same Meister M who is represented in this manuscript with 7 leaves, also appears in our prayerbook with a series of leaves.7

St Trond or Truiden, established in 1226–1231, was the first Franciscan establishment in the Netherlands. If the manuscript were from St Trond, that would make sense: it would account for the fact that the Drugulin manuscript and Add. 24332 are conceptually similar yet stylistically diverse. Franciscans in St Truiden and those in Maastricht could have worked closely together, and they could have exchanged ideas about how to make and organise manuscripts, and how to tap into the new technology of printmaking. But was Andresen correct? Was Drugulin’s manuscript made at St Trond/Truiden?

- 8 Ursula Weekes, Early Engravers and Their Public, pp. 121–43, 303–05.

13Tackling this question involved thinking about another clue in the calendar: 9 September is listed as the feast of the dedication of the church. But which church was this? Did it mark the date of the church consecration in Maastricht or St Truiden or some other Franciscan church? To find the answer to this question, I emailed Bert Roest, a scholar of Franciscans based in the Netherlands, who did not know but suggested I ask the Franciscan Study Center in St Truiden (the Instituut voor Franciscaanse Geschiedenis). I had visited them in 2000, when I studied and photographed a treasure in their collection, a manuscript that contained prints pasted in it. Back then I had shared the photographs with James Marrow, who rephotographed the book and gave the images to Ursula Weekes, who went on to write about the manuscript very intelligently.8 Alas, the modern brothers in St Truiden did not know whose dedication feast took place on 9 September. Finding a match proved difficult. Few calendars list a feast for a church dedication, so I had to hunt around for several months. I was living in the Netherlands at this time, so had many relevant manuscripts — those from the eastern part of the Northern Netherlands — available to me. A new spreadsheet took form as I logged the contents of several calendars. Arrays of data help not only to organise information but also to generate new knowledge. From the spreadsheet, I learned that Leiden UB, Ltk 303, which had a similar eastern Netherlandish dialect to Drugulin’s manuscript (Add. 31002), had an entry for 9 May which specified ‘kerk wijnghe [sic] Tongeren’ (church dedication in Tongeren). So I now knew that Andresen’s proposal that Add. 31002 had been made for Tongeren was incorrect.

14Another manuscript provided a positive identification for the church dedication on 9 of September. For that date, Maastricht, RAL Ms. 462 announced the ‘Kercwijnghe S Servaes’ (church dedication of St Servatius). Now I had a match. St Servatius, of course, was the dedicatory saint of the main church in Maastricht, and RAL Ms. 462 was made in Maastricht for the female Franciscan convent, Maagdendriesch (mentioned earlier). I therefore had an answer: Add. 31002 must have been made for use in Maastricht. In other words, the calendar suggested that Add. 31002 was made by the same beghards who made Add. 24332, but a generation later, using a mishmash of manuscript exemplars. It testifies to a world changing rapidly under the beghards’ feet. It is possible that the sisters of Maagdendriesch made Add. 31002, using prints and calendar/table of contents technology borrowed from the beghards, although there are no manuscripts from the female tertiaries in Maastricht that resemble it.

15On another note, I did look through every paper and digital database of manuscripts in Liège to search for the other manuscripts with prints that Andresen mentioned. And I went there on 11 July 2009 to search in person: I found no manuscripts with prints, but many with fascinating illumination. My search for Weigel’s manuscript with 58 prints stuck in it ended without satisfaction. Like much of the material culture of Europe, these manuscripts were probably disrupted by the First and Second World Wars. Maybe publishing this book will shake them out of hiding.

Similarities Between Add. 24332 and Add. 31002

- 9 London, BL, Add. Ms. 31002, Part I contains the calendar plus the folios originally foliated 1–197 (...)

On my next visit to the British Library, I went to study Add. 31002 and the attendant asked me which volume I wanted. This question caught me by surprise. Although Priebsch and the BNM had described Add. 31002 as a single volume, I now discovered that, in fact, the manuscript had been split into two. At some point during the ten years and four months between the accessioning of the individual prints and the transfer of the manuscript skeleton to the Manuscripts Department, the conservators at the BM must have rebound the manuscript. Rebinding was undoubtedly necessary after 200-odd leaves and prints were removed from the manuscript, which must have weakened it and made its covers fit too loosely. Rather than adding blank sheets to represent the missing folios (as the restorers had done with Add. 24332), they collected the folios into two thin volumes that mostly accounted for the text-only leaves and leaves that had blank, gluey rectangles where prints had formerly been pasted.9 Seeing the two volumes together, along with the more than 200 prints, provides a much fuller picture of the original production.

16Although Add. 31002 was made about 25 years later, it has conceptual similarities with Add. 24332. Like its predecessor, Add. 31002 has a calendar that also functions as a table of contents. The scribe of 31002 must have copied the concept from Add. 24332, for this is an extremely unusual feature, as I have shown above in Chapter 2. Objecting to the haphazard way in which the Roman numerals were listed in the earlier manuscript, the scribe of Add. 31002 ruled the calendar so that the foliation numbers occupy their own column (see fig 97 and 98). Furthermore, he standardised these numbers by making them all red, and he abandoned the confusing Roman numerals in favour of Arabic numerals, which are much easier to read, cause fewer errors, and take up less space on the line.

17Another similarity was pedagogical. I have proposed that the brothers had used Add. 24332 as a prayerbook, but also as a book for teaching reading and the rudiments of the religion, which warranted the extensive instructions on how to use the book. Unlike Add. 24332, Add. 31002 does not contain the Pater Noster and the other texts for teaching new readers; however, it does have a multiplication table (fig. 99). Unfolded for use, it becomes larger than the book block. This table is spread over 3 folios, with the numerals 1–17 down the first column, and 1–32 across the top, so that the square at the lower right of the table contains the number 544, which equals 32 x 17. That someone overcame the challenge of creating a table outwith the normal size and had to prepare it separately from the other folios, suggests that its inclusion was highly desired. It also demonstrates a commitment to ordering information in tabular form, and an almost cultish zeal for numerical sequencing and mathematical operations. The multiplication table may relate to one of the prayerbook’s functions, to teach students (children?) mathematical basics. Although such operations are required for calculating Easter, the central feast of Christianity, this table is not contextualized as a tool for Christian utility, but rather as one for pure knowledge, which is indeed highly unusual in a prayerbook.

- 10 The original foliator made some errors, so that there were two folios inscribed ‘235’ in Add. 31002

18Like Add. 24332, the later manuscript also includes prints used as pages, as well as prints used as historiated initials, and prints mounted onto blank pages. Most of the prints fell into this third category — trimmed and pasted to the written page. Those who lifted them later did so cleanly most of the time, but occasionally peeled up only a layer of the printed paper, thereby damaging the image, as with an engraving depicting Mary Magdalene (e-fig. 71). But some prints became the page, as with an engraving depicting the Virgin of the Sun (e-fig. 72), which became folio 235.10 The ink has severely bitten through the printed paper, but not through most of the text pages, which were made with thicker paper. One wonders how soon after its creation it began to autophage, and whether the printmakers envisioned their wares being put to such a purpose. If they had, perhaps they would have used tougher paper.

BM 1868,1114.221 — Mary Magdalene (e-fig. 71)

Mary Magdalene. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.221.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/82930606

BM 1868,1114.207 — Folio removed from the beghards’ (e-fig. 72)

Folio removed from the beghards’ later book of hours, formerly fol. 235, with a hand-coloured engraving depicting Virgin in sole. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.207.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/16858f27

19Like the earlier manuscript, Add. 31002 also contains coloured drawings, which depict saints unavailable as prints. Whoever cut up Add. 31002 in the nineteenth century must have had such a low opinion of these that he did not bother to cut them out, and three drawings therefore remain in the manuscript. One of these miniatures depicts St Lambert as a bishop with a bishop’s crook, a sceptre, and a book, trampling a figure wearing a Jew’s hat, indicating that Lambert converted the Jews by force (fig. 100). St Lambert was venerated in Maastricht.

Fig. 100 Folio in the beghards’ later book of hours, with a coloured drawing depicting St Lambert. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. II, fol. 106r.

A second drawing still in the manuscript represents a small surprised-looking acolyte kneeling at the skirts of his patron, St Francis, whose bare beet and upraised hands reveal the stigmata (fig. 101). Possibly the drawing is meant to show St Francis receiving the stigmata in the presence of his acolyte Brother Leo; it has been greatly simplified, due to the artist’s limited skills, and the draughtsman has omitted the usual flying Jesus and has represented the Leo figure as a beghard, comparable to the kneeling beghard figures drawn into the folios of Add. 24332. In this way, the drawing further connects Add. 31002 with a Franciscan community. It also suggests that the beghards themselves did not produce prints; if they did, they would certainly have mechanically produced numerous images of St Lambert, St Francis, and other saints of local importance, but the book’s makers were apparently unable to obtain these as prints and instead had to create homespun versions of these locally important subjects.

Fig. 101 Folio in the beghards’ later book of hours, with a coloured drawing depicting Brother Leo kneeling before St Francis. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. II, fol. 114v.

A third drawing in Add. 31002 depicts a church and accompanies ‘a prayer for the dedication of the church’ (‘een ghebeet van der kerckwijdijnghe’; fig. 102). The prayer is a transcription of the prayer from Add. 24332, folio ccc xcij, and the church is positioned at the upper left-hand corner, much like the position of the print of a church in the earlier manuscript (686–687) (e-fig. 20). Clearly, the beghard did not have an appropriate print depicting a church; instead he drew this church simply with a ruler for the verticals and relying on the ruling of the page for the horizontals, and then gave his creation weathervanes in the form of pen flourishes. Although prints must have become increasingly available after the turn of the century, the subjects of those prints was determined by the producers, not the consumers.

Fig. 102 Folio in the beghards’ later book of hours, with a coloured drawing depicting a church. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fol. 50v.

25 Years Later

I viewed Add. 31002 on 26 April 2006, again in December, and then on 17 May and 7 July 2007, revelling in the weirdness of the manuscript each time. When I had first looked at the manuscript, I had not suspected that it also came from the beghards of Maastricht because the style differs considerably from that of the earlier manuscript. Whereas the earlier calendar has many blank dates, the later one has a saint for every day of the year and has filled the blanks with such little-known saints as Zoe of Rome and Mary of Oignies. What confused me, and still confuses me in fact, is that the litany in Add. 31002 does not fully point to the beghards: Johannes, Trudo, Hubrecht, and Barbara are stroked in red. (My earlier hypothesis, that the manuscript may have originated with the tertiaries of Maagdendriesch, partially fits these observations, since they were dedicated to St Andrew & St Barbara; however, one would expect more fanfare than red stroking for Barbara’s feast. As an apostle, St Andrew would be red in any calendar.) The beghards of Maastricht remained the most likely producers of the richly illustrated Add. 31002. It is possible that the beghards made this manuscript for consumption by another religious house, just as they bound manuscripts for other monastic houses.

20Technology had shifted during the two-and-a-half decades since the beghards had made Add. 24332. Whereas the earlier manuscript constituted a group effort, a single hand wrote the later manuscript. Whereas the beghards had not come up with the idea of pasting in prints until they were part of the way through Add. 24332, they of course possessed the idea from the beginning of Add. 31002, and they had prints available from many more printmakers. Engraving had almost completely replaced woodcuts. If the beghards indeed made Add. 31002, they were now celebrating the dedication of the church of St Servatius, the main church of Maastricht.

21Add. 31002 is extraordinary because it spans categories. It is a manuscript, yet was made deep within the printed book period (c. 1525). Instead of being made on paper, it is made on a combination of materials, with the calendar, the fold-out computational diagrams, and first and last folio of every quire made on parchment, so that the parchment falls on major text breaks, and the rest paper. This also allows the most decorated parts of the book to fall on parchment, which holds paint better than does paper. The folios have numerous places for prints, mostly roundels, throughout the book, and these are decorated with penwork. In some cases, one can see the planner’s instructions for which image belongs where, such as ‘Veronica’ (fig. 103). Electronic reconstruction reveals what the page originally looked like (fig. 104). From this example it is clear that the scribe had a stack of images before him and measured out the print onto the text box in order to inscribe around the empty rectangle. In other words, the prints were planned from the beginning and not an afterthought.

22Earlier I mentioned another similarity: an engraving depicting St Mark appears in fine impressions in both manuscripts (1861,1109.643 and 1868,1114.114, e-fig. 12 and e-fig. 61). In the earlier manuscript, the designer has pasted an extra lion onto the page, and drawn a chapel around it with rubricator’s ink, features that are lacking in the later manuscript. One narrative that could explain how these two impressions of the same print appear in the two manuscripts is this: the beghards acquired hundreds, if not thousands of prints, beginning in or before 1500, and used them to illuminate the manuscript prayerbooks that they manufactured in their monastery, an activity they concentrated on after several of their looms were removed by the Maastricht city council. Many of these prints they were able to acquire in multiple copies; they possessed so many of certain prints around 1500 that they were still using them in the 1520s.

23Furthermore, the aesthetics of colouring had changed significantly in the intervening years. As I looked through these prints, I noted that they all had similar hand-colouring in light washes (with a few minor exceptions), presumably by the same person. This situation was quite different from that in Add. 24332, in which groups of related prints were hand-coloured the same. These observations suggested that in the earlier example, from 1500, the beghards bought groups of prints from various sources, and that some of them were delivered already hand-coloured, whereas the later beghards must have received unpainted prints, and applied washes to them themselves. It is possible that these two examples describe a larger trend: before 1500 or so, prints were more rapidly available pre-coloured, whereas a generation later, the standard had changed.

24A handful of earlier prints used in Add. 31002 that were coloured in a different palette provide an exception. These, I suspected, had been in the beghards’ possession for decades, and they had received them already coloured before 1500. Leaves in this category include 1868,1114.168, which showed St Bartholomew (e-fig. 73).

Fig. 103 Folio in the beghards’ later manuscript with a space reserved for an image of Veronica. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. II, fol. 34r.

Fig. 104 Electronic reconstruction of Veronica page: superimposition of London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.24 onto London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. II, fol. 34r.

BM 1868,1114.168 — St Bartholomew (e-fig. 73)

St Bartholomew. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.168.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/c4171f63

- 11 Lehrs notes that this section of the Creed is usually brandished by St Simon, not Bartholomew; howe (...)

Lehrs had attributed this image to Israhel, and then Hollstein disattributed it. Relevant here is that the print probably dates from the 1470s, and the beghards may have had it for more than 50 years before incorporating it in their book. I wondered whether they had another copy, which they had inserted into Add. 24332; however, my spreadsheet did not reveal an appropriate place for such a St Bartholomew print in that book. Nevertheless, this print, like many others, reveals layers of secrets: Lehrs had noted that the label ‘Scs Bartholomeus’ was engraved into the plate but that the letters had been added by a different hand. The text on the banderol (‘Ascendit ad celos, sedet ad dexteram dei patris omnipotentis’) is part of the Apostles’ Creed.11 Here is a scenario to explain this: by 1500 the beghards had realised how useful prints were for ‘illuminating’ manuscripts. They were frustrated that the available prints did not perfectly meet their needs, so they hand-drew a few essential images in their books or, in some cases, they adjusted existing images, for example changing an attribute or an inscription. In this case, a printmaker realised that an image of St Bartholomew, with his name in bold letters, would be much appreciated by the beghards of Maastricht. That printmaker had a plate with the apostle, but he recut the plate to add the name Bartholomew to the bottom. The image would have formed the corporate mascot for the beghards. To make any fewer than, say, 100 copies, would not have warranted re-cutting the plate. The beghards used them, and gave them, perhaps, to those who heard them preach. But this is the only one that survives. In other words, someone had underscored Bartholomew’s identity so that it would be unmistakable, so that the print would become an appropriate calling card for the beghards of Maastricht.

25Lehrs points out that this is a unique impression, so if the beghards did make or order numerous copies, they have now been lost. I could imagine, however, that the beghards, having learned about the use of prints 25 years earlier, were finding ever more applications for them, and that early on in their discovery of prints, they wanted to have a print depicting their dedicatory saint. As ever, the problem with prints is their fixedness. Mechanical reproduction comes at the cost of rigidity. Once an image was made, it could depict, say, St Wolfgang, until someone went to great lengths to scratch out that saint’s attribute and transform him into St Servatius. But rather than change every finished print, one could also adjust the plate. Or take an old and somewhat worn-down plate, re-inscribe the lines, and take the opportunity to make other adjustments as well. It is difficult to know whether the beghards were dealing with the printers themselves, or whether they were buying the prints from middlemen on the river. Whatever the system was, it allowed for the consumer (the beghards) to get a message back to the producers that they wanted printed images depicting St Bartholomew.

Dating the Later Manuscript

- 12 London, BL, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fol. 75v.

Add. 31002 contains features that help to date it, or at least give it several ‘earliest possible dates’. For example, there is a reference in Add. 31002 to Julius II (pope in 1503–1513),12 which provides a terminus post quem for the writing of the manuscript, although the manuscript clearly is much later than 1503. Prints themselves also provide clues for dating the book. In particular, the youngest prints in the manuscript can help to date its production. Young, datable prints include a reverse copy of an engraving made c. 1519 by Albrecht Dürer (e-fig. 74).

BM 1868,1114.27 — After Albrecht Dürer, Crucifixion roundel (e-fig. 74)

After Albrecht Dürer, Crucifixion roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.27.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/66ce57c7

- 13 Confusingly, this is not the same person as the ‘Monogrammist IB’.

It depicts the Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary, St John, and the Magdalene embracing the bars of the Cross. As it is a copy of Dürer’s work, it must therefore postdate c. 1519. Among the other young prints is an engraving representing St Helen made by an anonymous German artist who signed his print with the monogram ‘IB’ and dated it 1523 at the upper right (e-fig. 75).13 Furthermore, the manuscript contains two prints by Jacob Binck (1494/1500–1569), a German artist who spent part of his career in the Netherlands and was especially active as an engraver in the late 1520s. Two engravings made by this artist are Christ as the Man of Sorrows (1868,1114.22) (e-fig. 76) and an Ecce Homo (1868,1114.69) (e-fig. 77).

BM 1868,1114.120 — St Helen (e-fig. 75)

St Helen, dated 1523, with the monogram ‘IB’. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.120.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/e2a03a80

BM 1868,1114.122 — Christ as the Man of Sorrows (e-fig. 76)

Jacob Binck, Christ as the Man of Sorrows. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.122.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/046cf84f

BM 1868,1114.69 — Ecce Homo (e-fig. 77)

Jacob Binck, Ecce Homo. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.69.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/3b054c33

Many of these later prints make use of Italianizing decorations. For example, St Trudo (e-fig. 78), which is sometimes attributed to Jacob Binck but is not signed, shows the saint nestled in a series of frames: large drapery with intricate edges that frames his body and face, and architectural frames with compound columns and swags cram the available space full of elaborate detail. Another ornate border, around a St Christopher, shows a number of hybrid creatures, putti battling, and decorative arabesques (e-fig. 79). Printmakers must have realised that printing the frames — or even using interchangeable frames — would save their customers the labour of having to add their own. This could have been a selling point for the printers.

BM 1868,1114.199 — St Trudo (e-fig. 78)

St Trudo. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.199.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b4d830d4

BM 1868,1114.150 — St Christopher (e-fig. 79)

St Christopher. Engraving used as a folio, removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.150.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/c983aac2

Finally, from the same period, there is one print made by Allaert Claesz, a Dutch printmaker who was active in the 1520s. The image represents St Lucy (with a knife in her neck) and St Genevieve (holding a candle), with a strongly Italianizing aesthetic communicated by the elegant garb of the women and the decorative nested frames (e-fig. 80).

BM 1868,1114.86 — St Lucy and St Genevieve (e-fig. 80)

St Lucy and St Genevieve. Engraving used as a folio, removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.86.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/e04ba44f

According to my analysis, the prints were not added later, but were part of the book from the beginning, and can therefore help establish a date for the production. In short, the dated and datable prints indicate that 1523 is the terminus post quem of Add. 31002. A date of c. 1525 (after 1523) therefore makes sense. This dating also reveals that even in the third decade of the sixteenth century the beghards were still obtaining prints from both Netherlandish and German printers.

Israhel van Meckenem

While the youngest prints in the manuscript helped to date the production, the oldest prints helped to establish a longer view of the beghards’ activities. Israhel van Meckenem, who was active from c. 1465 until his death in 1503, made some of the earliest prints in Add. 31002. I suspected that these, and other early prints used in the book, had been stored in the monastery since the end of the fifteenth century. Although only these two books of hours from the beghards’ workshop have come to light so far, one can imagine that the beghards were making similar books filled with prints continuously for several decades.

26Israhel supplied the book’s two grandest prints in the form of large roundels. One depicts the Annunciation (e-fig. 81) and the other depicts Christ with the Arma Christi with ‘ecce homo’ inscribed on the scroll (e-fig. 82).

BM 1868,1114.109 — Israhel van Meckenem (e-fig. 81)

Israhel van Meckenem, Annunciation. Engraving used as a folio, removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.109.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/89d6e804

BM 1868,1114.28 — Israhel van Meckenem (e-fig. 82)

Israhel van Meckenem, Christ with the Arma Christi; on the scroll: ‘ecce homo’; below the borderline, signed ‘Israhel’. Engraving used as a folio, removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.28.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/dce280fb

27The beghards have taken the round prints and trimmed them to fit a rectangular page, thereby turning them into whole pages of a small manuscript rather than embellishments to a large one (probably the artist’s intended purpose). One can imagine that the beghards had obtained these prints at the end of the fifteenth century, but had failed to find a place for them in Add. 24332, since they are large, round objects. In the 1520s the beghards found a way to put a round object in a rectangular frame: just trim it with a knife.

- 14 For both letters, including references for uncut versions, see Lehrs, vol. IX (https:// digi.ub.uni (...)

- 15 I thank Margaret Bent and John Harper for this suggestion.

- 16 London, BL, Add. Ms. 24332 uses Israhel’s roundels in the prescribed manner. A hand-painted version (...)

28When viewing the image of the Annunciation in its uncut state, its original purpose becomes clear: the image functioned as a large letter D. Seen in relation to the Annunciation engraving, the image of Christ as Man of Sorrows also comes into focus as a letter O.14 Both images are signed Israhel in the plate below the borderline, but it seems that the artist meant this to be trimmed off before use because the image was intended as an entire letter itself, not just an image to be stuck into a hand-rendered letter. It is possible that the Annunciation in the D could have been designed for a book of hours as the beginning of the Hours of the Virgin (Domine labia mea aperies…), and that the Christ as Man of Sorrows in the O could initiate the Gregorian verses (O, Adoro te in cruce…). However, the prints are really too large for a book of hours (which is why they were trimmed for use in Add. 31002: to fit into an octavo-sized book), and they would make much more sense in a larger book type. Israhel must have intended them to function as instant historiated initials for large manuscripts, perhaps folio-sized choir books, to mark the incipits of texts related to the Annunciation and Passion, respectively. For example, the D with the Annunciation could be for an Antiphonal to mark the first Sunday in Advent (Dominica Prima Adventus).15 He was trying to exploit the market of manuscript-makers to create specific prints that would save them labour, providing the whole package, letter and image, which could be hand-coloured by someone of limited skill. I have found few examples in which manuscript-makers used Israhel’s prints in the way that he had intended.16

29Israhel van Meckenem was not the first to make prints for the manuscript industry, but he made the widest range, and his prints are the easiest to spot, since he mechanically repeated his signature on the uncut sheets. As with all new media, dispersing the media disperses not only the content (such as a saint, a miraculous image) but also the idea of the new medium (prints themselves as a replacement for illumination). It is not surprising, therefore, that other printmakers, such as an anonymous Netherlandish engraver, similarly made historiated letters that could simply be glued in place (e-fig. 83).

BM 1868,1114.32 — Christ as Man of Sorrows with the Arma Christi in a letter O (e-fig. 83)

Christ as Man of Sorrows with the Arma Christi in a letter O. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, BM, P & D, 1868,1114.32.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/6d2fc836

It depicts Christ as Man of Sorrows amid the Arma Christi in a letter O. Unlike Israhel’s enormous letter (92 millimetres high) brandishing the same subject, this one is made for an octavo-sized book, as a commanding and large historiated initial. With the print nearly the same width as the text block, the scribe has only been able to fit a thin column of text beside it. Undoubtedly, the engraver was responding to book makers’ desiderata for this iconography, so that they could include images of this subject alongside a prayer beginning ‘Adoro te’, which carried a large indulgence. At the top of the sheet is the tail end of the rubricated indulgence, announcing 6666 (years’) indulgence. The printmaker must have known that a scribe could adjust the prayer so that it began ‘O’ in either Dutch or Latin.

30Beghards used prints by Israhel in their early and their late experiments. Were Israhel’s prints simply cheap and available? Or did the beghards favour them and seek them out? Available evidence does not answer these questions. What it does tell us is that Add. 31002 contained prints from several different series that Israhel signed, including his ‘Memento mori’ series. Like his page of roundels with saints, discussed in the previous chapter, this sheet he apparently sold whole. Users, in this case the beghards, would cut the sheet apart and use the printed roundels separately. Several of these sheets of roundels are preserved intact, such as one in the British Museum (e-fig. 84). The beghards used at least one of these roundels in Add. 31002; it shows death visiting the Pope (e-fig. 85).

BM 1848,1125.19 — Israhel van Meckenem’s roundels (e-fig. 84)

Israhel van Meckenem’s roundels, intact, with death theme. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1848,1125.19.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/73ad2a6f

BM 1868,1114.74 — Israhel van Meckenem (e-fig. 85)

Israhel van Meckenem, Death visiting the Pope, roundel from Memento mori series. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.74.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/960bc5aa

One might expect that the other roundels from the same sheet would appear in Add. 31002, but they do not. Perhaps the beghards had already used the other prints in previous projects, such as Add. 24332, their book of hours from 1500. Copies of the roundels on this sheet may have been removed from initials there, where square holes now remain.

31The beghards had multiple sheets of Israhel’s roundels available to them, and at least three other roundels within Add. 31002 come from another series he made: the Nativity (e-fig. 86); Presentation in the Temple; (e-fig. 87); Circumcision of Christ (e-fig. 88); and the Virgin of the Sun, half-length and cupped in a moon (e-fig. 89). These roundels were cut from a sheet bearing Israhel’s name elaborately engraved in prominent letters at the bottom (e-fig. 90). That some of the sheets remain intact suggests that people kept them as collector’s items from their inception, no doubt made more precious by the artist’s audacious branding of the object.

BM 1868,1114.209 — Nativity (e-fig. 86)

Israhel van Meckenem, Nativity roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.209.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/2a22e9e7

BM 1868,1114.96 — Presentation in the Temple (e-fig. 87)

Israhel van Meckenem, Presentation in the Temple roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.96.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/abd2bdbf

BM 1868,1114.84 — Circumcision of Christ (e-fig. 88)

Israhel van Meckenem, Circumcision of Christ roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.84.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f2fd8c27

BM 1868,1114.43 — Virgin in sole (e-fig. 89)

Israhel van Meckenem, roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.43.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/24c07a98

BM 1873,0809.641 — Sheet of 6 roundels (e-fig. 90)

Israhel van Meckenem, Sheet of 6 roundels depicting Christ as Man of Sorrows, the Virgin of the Sun, and 4 scenes from the Infancy of Christ. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1873,0809.641.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/c49908ee

Fig. 105 Folio from the beghard’s later manuscript with a prayer, an indulgence, and a blank area where a Marian roundel was formerly pasted. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fol. 76r.

These and other roundels have been accessioned into the British Museum without their respective manuscript substrates. The folios from which small prints were steamed reveal something of the making process. For example, one emptied roundel has the letter M inside, to which someone has added ‘Maria’ (to be read vertically, from bottom to top) to clarify what was to be glued onto the blank (fig. 105). Other folios with prints that have been steamed off reveal that someone used this same technique of planning out the book, jotting down the name of the saint that should eventually be pasted in. For example, the preceding folio formerly bearing an image of the Virgin has a similar guide word (Add. 31002, Vol. I, fol. 75r; fig. 106). This suggests that the prints were measured and planned as the scribe was writing, but that they were glued in afterwards. Perhaps the beghards separated the operations of writing and gluing, because writing on a freshly glued page could be damp and lumpy. Separating the tasks, and dividing the labour, was part of the general trend towards efficiency. This is different from the process by which Add. 24332 was made, as described earlier, in which the scribe seems to have pasted in images as he went along.

Fig. 106 Folio from the beghard’s later manuscript with a prayer and a blank area where a Marian print was formerly pasted. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 31002, vol. I, fol. 75r.

Apparently, the beghards bought several sheets of Israhel’s printed roundels when they had the opportunity to do so. From such a sheet, they used in a manuscript his image of SS Cosmas and Damian (e-fig. 91); a SS Francis and Clare (e-fig. 92); and a SS Dominic and Catherine of Siena (e-fig. 93).

32These have all been cut from a single sheet, signed by Israhel van Meckenem (e-fig. 65). It is possible that they used the other three for the earlier project. In fact, the roundel with St Ursula would fit perfectly in Add. 24332, on folio cccc xlij (396). A fuller picture of the beghards’ access to and use of prints emerged not only when I reconstructed both manuscripts, but also when I considered the two manuscripts together. One scenario that fits the evidence is this: the beghards bought single sheets of several of Israhel’s roundels, with six subjects to a page, in or shortly before 1500. They cut the roundels apart and then used several of them in Add. 24332. Most of these were recognised by a nineteenth-century collector and removed with a knife, leaving square holes in the page. Only three of these survived in the manuscript at the time it was sold to the British Museum. The BM removed these remaining three, and accessioned them in Prints and Drawings. In the 1520s in Maastricht, the beghards used more of the Israhel roundels in their subsequent experiments involving gluing prints to manuscripts. Many more of these roundels survived in Add. 31002, until 1868 when the BM steamed them all off and accessioned them.

BM 1868,1114.178 — SS Cosmas and Damian (e-fig. 91)

Israhel van Meckenem, SS Cosmas and Damian roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.178.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b139197d

BM 1868,1114.158 — SS Francis and Clare (e-fig. 92)

Israhel van Meckenem, SS Francis and Clare roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.158.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/3805277f

BM 1868,1114.117 — SS Dominic and Catherine of Siena (e-fig. 93)

Israhel van Meckenem, SS Dominic and Catherine of Siena roundel. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.117.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/cb7df4d6

33In addition to the sheets by Israhel, the beghards had access to other sheets of roundels. In fact, they used another sheet of roundels intact and inserted the entire thing as folio 366 in the original Add. 31002 (e-fig. 94).

BM 1868,1114.188 — Five roundels depicting the most lucrative indulgenced images (e-fig. 94)

Five roundels depicting the most lucrative indulgenced images. Hand-coloured engraving used as manuscript page, removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.188.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/4b46faac

- 17 For the Mass of St Gregory and ideas about purgatory, see Rudy, Rubrics, Images and Indulgences in (...)

The maker of this page of roundels, who signed the print ‘+ML’, identified the most potent indulgenced images and printed them together as a single sheet, so that five circles each contain a devotional image: Christ as the Man of Sorrows standing in his tomb with the Arma Christi (the Gregorian vision); the Virgin and Child with St Anne; the Virgin of the Sun; St Veronica holding the sudarium; and the initials ‘IHS’ in sole. St Gregory’s vision was well-known as an image that activated a prayer beginning ‘Adoro te in cruce pendentem’, which granted the votary thousands of years of purgatorial remission.17 Likewise, the votaries had to view an image of the Virgin of the Sun in order to win an indulgence of 11,000 years.

34This printed leaf has been used as a page in a prayerbook and therefore was inscribed on the back. While the printer probably conceived these five as separate images to be cut apart, possibly to create instant historiated initials, it is not clear why the book maker left the sheet intact: possibly it was to multiply the benefits of the images grouped together on the single page. Other, larger, full-page versions of each of these subjects appeared elsewhere in the manuscript, so perhaps here the book maker was simply experimenting with the form. This is yet another way that, by ca. 1525, the beghards were bending the prints to their own requirements, having had at least 25 years’ experience making such manuscripts and wrestling the rigid objects into their new manuscript creations. Rather than cutting the sheet apart, the beghards chose the path of least resistance and simply used the entire sheet as a page, foliating it ‘365’ at the top. It is clear that the market was trying to supply book makers with new wares, but that sometimes the market misjudged its buyers’ needs. Users adapted the prints accordingly.

35The beghards had other prints that have been attributed to Israhel, including an engraving depicting St Quirinus that gives the saint the haughty look of a noble knight (e-fig. 95). This, like other engravings of saints, was cut from a larger sheet. It is possible that the beghards bought two or more copies of this print when they had the opportunity in or shortly before 1500. It would have fitted thematically on the now-missing fol. ccc lv of Add. 24332 (see the Appendix).

BM 1868,1114.116 — St George/Quirinus (e-fig. 95)

Israhel van Meckenem, St George/Quirinus. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.116.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/1fc325da

Whereas the nineteenth-century curators in London created mounts on which they juxtaposed related prints — often those they assigned to the same hand or ‘school’ — the curators in Paris went a step further and reconstructed sheets of prints. For example, they placed their copy of the St Quirinus alongside the three other prints from the same sheet (fig. 107). Whereas the SS Cornelius, Hubert, and Quirinus prints had apparently survived in someone’s print collection where they remained quite clean, the fourth print in the group — of St Anthony — was gleaned from some other source (a prayerbook?) where it had been used and soiled. Parisian curators brought the four saints back together on the page, lining them up as if Israhel had just printed them there. Clearly, their first intention was to pay homage to the master, to reconstruct his oeuvre, at the expense of showing the prints’ original context or function. By literally trimming off that context, they have made it especially difficult to reconstruct.

Fig. 107 Israhel van Meckenem, St Quirinus and three other saints, separate engravings mounted on one sheet. Paris, BnF, Département des Estampes, Ea48aRes (IvM). Published with kind permission from the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

This says much about nineteenth-century sensibilities. They valued the hand of the maker, in other words, genius. It also explains why so many engravings were attributed to Israhel. ‘Genius magnetism’ is especially prevalent in fifteenth-century art, when only a few makers signed their works. Meanwhile, the large anonymous remainder is more difficult to categorise, and somehow less satisfying, because it is easier psychologically to imagine the past if one can populate it with proper names. The nineteenth-century project of cataloguing required that objects be categorised by names, and that the genius’s creations be reassembled chronologically into early, middle, and late periods. Many other prints were assigned to Israhel, making his output appear even larger than it was. Some of the unsigned objects, which were deemed lower in quality, could easily slide into his early period, or be deemed prints made from reworked plates.

36Nineteenth-century cataloguers revelled in attributing other engravings from Add. 31002 to Israhel, including, for example, an engraving depicting Christ at Emmaus (e-fig. 96).

BM 1868,1114.37 — Christ at Emmaus (e-fig. 96)

Christ at Emmaus. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.37.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b2b6888f

This engraving comes from a large suite comprehending 55 sheets in several variations. Lehrs attributed the series to Israhel, claiming that he copied it from the so-called Master of the Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand, which in turn, was largely copied from a series by the Master of the Berlin Passion. In other words, Lehrs constructed a complicated pedigree for this and a group of related prints.

37Lehrs also attributed a group of apostles to Israhel. These early prints include the engravings depicting St Mark and St Bartholomew discussed earlier (e-fig. 73) and a closely related St Luke (e-fig. 97).

BM 1868,1114.184 — St Luke (e-fig. 97)

St Luke. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.184.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/5fc58440

Lehrs thought that these came from the same apostle series and were by Israhel, but Hollstein did not think the prints were by him. They are, however, from the late fifteenth century: this can be established because the St Mark also appears in Add. 24332, whose terminus post quem is 1500. From this one can deduce that the beghards had purchased a great number of prints before 1500 and still had not exhausted the supply in the 1520s, while at the same time replenishing the supply with new prints, made by both German and Dutch printmakers. These apostle prints are in a much older style than the other prints that the beghards added to Add. 31002; assuming that they purchased them before 1500, they therefore had them around for more than 20 years before inserting them into Add. 31002. Either they possessed a large supply of prints, or else they had a small, precious cache and used them slowly. Lehrs also assigned an engraving depicting the Circumcision of Christ to Israhel van Meckenem (e-fig. 98) asserting that he had copied it from the Master of the Berlin Passion.

BM 1868,1114.85 — Circumcision of Christ (e-fig. 98)

Circumcision of Christ, attributed to Israhel van Meckenem. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.85.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/91db362d

It is possible that the beghards obtained this print around 1500, together with others from this series, including that of Jairus’s Daughter (1861,1109.636), to which it is closely related (e-fig. 55).

- 18 For a discussion of attributions to this artist, see Weekes, Early Engravers and Their Public, pp. (...)

38Some early prints simply did not fit into these neat categories, so the cataloguers grouped them and came up with new personalities for them, often with unfortunate names. One of these was the Master of the Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand. This artist became a catch-all for engravings of middling quality, which were not quite good enough to attribute to Israhel.18 One of these, for example, represents the Virgin Mary as a child climbing the steps of the Temple (e-fig. 99).

BM 1868,1114.197 — Virgin Mary as a child climbing the steps of the Temple (e-fig. 99)

Virgin Mary as a child climbing the steps of the Temple. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.197.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/93ffcf6d

It was claimed that the Master of the Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand copied it after the Master of the Berlin Passion, one anonymous entity copying another.

39I am not interested here in arguing with, or refuting, the lineage of these prints according to Lehrs and Hollstein, but I want to make three points: first, that nineteenth-century cataloguers were quick to attribute prints to Israhel. Second, that in the late fifteenth century the market for prints was growing quickly enough to support several different printers in the Rhine basin making series of similar prints, depicting the lives of Jesus and Mary. They exploited the growing market by engraving their own sets of plates (or refreshing existing plates), making subtle changes. In the end, they made a living by copying the copies. And third, that regardless of whether Israhel made this particular print or not, he was particularly adept at scooping up prints, series, and ideas and remaking and rebranding them. Part of his innovation was to churn out prints, anticipating a large number of needs and potential uses, and to distribute them widely and aggressively.

Conclusion: Changes Over Three Decades

Because the beghards of Maastricht made at least two manuscripts with pasted prints, comparing the early one (Add. 24332) with the late one (Add. 31002) reveals changes in the types of prints available from 1500 to ca. 1525, in the subjects and media of those prints, and corresponding shifts in devotion. Beghards were obtaining prints from a variety of sources over the course of several decades. In Add. 24332 the earliest prints might date from the 1460s, and the latest prints in Add. 31002 from the 1520s. Thus, they were dealing with printmaking as it developed over 70 years. These prints were made with a variety of media, in different sizes, shapes, and dimensions. As this evidence has suggested, when the beghards wrote and assembled Add. 31002 ca.1525, they still had a number of early (that is, pre-1500) prints available to them.

- 19 For a detailed history, see Anne Winston-Allen, Stories of the Rose: The Making of the Rosary in th (...)

40The early and the late manuscript differ in their attention to saints. The calendar in Add. 31002, which has been turned into a table of contents, indicates that it originally had far fewer suffrages and individual prayers to saints than did Add. 24332. Whereas there is only one Rosary prayer in Add. 24332, Add. 31002 has several, with an entire bouquet of images of the Virgin of the Sun, the Virgin of the Rosary, the Apocalyptic Virgin, and related imagery that grew up to meet the demands of the Rosary devotion.19 In the intervening years between 1500 and ca. 1525, many more prints relevant to these devotions became available. I suspect that they were even cheaper by ca. 1525, and they were quite commonplace.

- 20 A similar strategy is described in Kathryn M. Rudy, ‘Reconstructing the Delbecq-Schreiber Passion ( (...)

41One major difference was in the attitude towards colour. For the earlier manuscript, the beghards used the prints in the way they had received them, either coloured or not. In the later manuscript, Add. 31002, the prints arrived mostly uncoloured. But the beghards must have taught themselves to hand-colour the images, for hundreds of them receive a similar treatment and palette. It is possible that they wanted to use colour in order to impose an evenness, a unity, on the images, which otherwise presented a hodgepodge of sizes, styles, and shapes.20 These prints bear coloured washes in characteristic tones, comprising a limited palette: yellow, orange-red (a colour often used for frames), and olivegreen washes, maroon (which has often flaked off), grey (which may be watered-down ink, as on SS Dominic and Catherine of Siena (e-fig. 93)), and occasionally teal (as on the robe that Death wears in Israhel’s Death visiting the pope, 1868,1114.74 (e-fig. 85), which the beghards applied to most of the prints in Add. 31002. Clearly, they had acquired the print in an uncoloured state, and then applied the colours themselves.

42A second major difference relates to experimentation and confidence: whereas Add. 24332 is uneven, with several scribes, emendations, and long sections without any prints, Add. 31002 is remarkably even throughout. Add. 24332 may represent the beghards’ first attempt at making a manuscript with prints; as I suggested in the previous chapter, the beghards began affixing the prints only after they had already begun copying the book, and they revised their methods as they went along. By the 1520s, they were thoroughly familiar with the technique and executed it evenly. Those later book makers were perfecting a system that had been invented a generation earlier, and they figured out how to use penwork to fill in gaps for awkwardly-sized prints.

- 21 That the beghards concerned themselves with indulgences is a topic I took up in a previous study: K (...)

43Another difference between the books concerns the content, both textual and visual. Add. 24332 contains numerous texts that offer indulgences, whereas the later book does not, with relatively few rubrics announcing them.21 It is possible that the controversies around indulgences — which ultimately led to the Protestant Reformation — had already made their mark on the beghard community by 1525, and that they were steering their devotions in other directions. Instead of indulgences, Add. 31002 emphasises the Rosary, with multiple prints depicting the Virgin within a string of beads. In one of these, the painter has carefully coloured the beads yellow and red, possibly to suggest amber nuggets with coral beads after each decade (1868,1114.172, e-fig. 100). Another shows the Virgin of the Sun appearing to St Dominic, which refers to the origin myth of the Rosary devotion (1868,1114.211, e-fig. 101). A third print of the same subject treats the image more simply (1868,1114.51, e-fig. 102). A fourth depicts the dragon below the Virgin’s feet, and emphasises the shape of the rosary with red roses (1868,1114.98, e-fig. 103). These closely related examples show the extent to which printmakers both responded to and also created a market for rosary paraphernalia.

BM 1868,1114.172 — Rosary print (e-fig. 100)

Rosary print. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.172.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/9d1ea162

BM 1868,1114.211 — Rosary image (e-fig. 101)

Rosary image, with the Virgin of the Sun appearing to St Dominic. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.211.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/e14aa8c6

BM 1868,1114.51 — Rosary image (e-fig. 102)

Rosary image, with the Virgin of the Sun. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.51.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/fe120a58

BM 1868,1114.98 — Rosary image (e-fig. 103)

Rosary image. Engraving removed from the beghards’ later book of hours. London, British Museum, Department of Prints & Drawings, inv. 1868,1114.98.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/ec7218ed

These rosary subjects did not appear in the beghards’ earlier manuscript. But one might ask how much these changes reflect changing notions of devotion. Perhaps printers were foisting particular kinds of devotion onto the public, because certain practices could be summarized by and reliant upon a single-leaf print. But to what extent did printers’ changing wares reflect the devotional tastes of the public, and to what extent did they shape those tastes? I shall argue that printmakers inflected the shape and content of manuscripts themselves. That they also encouraged the public to participate in an image-centred devotion (for which the printmakers could supply the images) seems entirely plausible.