Thomas Annan of Glasgow

|4. Landscapes

Volltext

1Like portraiture, landscape was a major genre of painting and was similarly adopted by the earliest photographers. As Ray McKenzie, a contemporary scholar at the Glasgow School of Art, notes:

Since the publication, in 1845, of William Henry Fox Talbot’s Sun Pictures in Scotland, landscape has been one of the most abiding obsessions in the Scottish photographic tradition. Aspects of the country’s physical appearance have proved a source of endless fascination both for indigenous photographers, as well as for those who, following Talbot, have come to Scotland for no other reason than to photograph it. […] There is scarcely a single early Scottish photographer of any note who did not at some point engage with landscape as a subject.

- 42 See Ray McKenzie, “A Love Affair with Loch Katrine: Problems of Representation in Early Scottish La (...)

2McKenzie draws attention to the role of the poems and novels of Scott in promoting landscape photography in Scotland. Thus Talbot’s Sun Pictures in Scotland, even though it makes no direct reference to Scott’s literary texts, “was conceived primarily as a tribute to Scott’s literary achievement,” while George Washington Wilson’s Photographs of English and Scottish Scenery: Trossachs and Loch Katrine. 12 Views (1868) actually incorporates extensive quotations from The Lady of the Lake, Scott’s narrative poem of 1810, the action of which unfolds in and around Loch Katrine and to which the lake owed its celebrity.42

3Thomas Annan probably had ample practice with landscape when working for the engraver and publisher Joseph Swan. He may have had occasion to examine the Scott-inspired Vues pittoresques de l’Écosse, consisting of about fifty views of Scottish scenes engraved by the Frenchman François-Alexandre Pernot, with texts based on the writings of Scott by Amédée Pichot, a prolific author of books about the British Isles and British men of letters (Paris, 1826 and Brussels, 1827) (Fig. 4:1).

- 43 See Smith, “Joseph Swan (1796-1872) engraver and publisher,” p. 92. Some of the photographs of land (...)

- 44 Thus, for example, Select Views of Glasgow and its Environs (see note 43 above); The Lakes of Scotl (...)

4He was almost certainly familiar with the books featuring Scottish scenes put out by both Swan43 and Blackie, the well-known Glasgow publisher who illustrated several of his publications of Scottish scenes and Scottish writers, such as Burns and James Hogg, with engravings of landscape paintings by David Octavius Hill (Figs. 1:4-6; 4:2-3).44

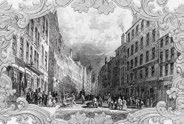

5Annan must have known the relatively inexpensive (twopenny) engravings of Glasgow buildings and city scenes published in 1843 by David Allan and William Ferguson, another local firm of lithographers and engravers, and reproduced in James Pagan’s popular Sketch of the History of Glasgow (Glasgow: Robert Stuart, 1847) (Fig. 4:4).

- 45 Ray McKenzie, “Thomas Annan and the Scottish Landscape: Among the Gray Edifices,” British Journal o (...)

6A commercial handlist with details of Annan’s photographic stock for 1859 included approximately 75 titles of landscapes and topographical works available in various print sizes and also in the then-popular stereo format. 45 Landscapes were also prominent among the works he selected for display at photographic exhibitions.

- 46 The 1857 and 1860 editions, from different Glasgow publishers, appear not to have included illustra (...)

7Annan produced landscape (and cityscape) photographs throughout his career, notably, in the 1860s, for the quarto edition of John Eaton Reid’s History of the County of Bute and families connected therewith (Glasgow: T. Murray, 1864), to which he contributed eight mounted albumen prints of 7 x 4¾ inches; for two volumes put out by the Glasgow publisher Andrew Duthie, Photographs of the Clyde (1867) and Photographs of Glasgow (1868, with text by Rev. A. G. Forbes); and for Duthie’s 1865 edition of Days at the Coast, a local bestseller by the popular Glasgow writer Hugh MacDonald, to which Annan contributed twelve plates (Figs. 4:5-10, 4:12).46 He also supplied landscape illustrations for an 1866 edition of Scott’s Marmion (London: A. W. Bennett).

8In addition, Annan was able to combine his skill as a photographer of artworks with his taste for landscapes, providing photographs of twenty paintings for Alexander Fraser’s Scottish Landscape: The Works of Horatio McCulloch R. S. A. (Edinburgh: Andrew Elliot, 1872). Landscape paintings also seem to have directly influenced his landscape photographs. A photograph, in Reid’s History of the County of Bute, of Glen Sannox on the Isle of Arran in the Firth of Clyde, for instance, appears to replicate the view painted by the popular Glasgow artist John Knox (Figs. 4:11-12).

- 47 Ray McKenzie, “Landscape in Scotland: Photography and the Poetics of Place,” in Light from the Dark (...)

9At the Edinburgh photographic exhibition of 1861, the British Journal of Photography praised “Loch Ranza” (another landscape from Arran that would be used in Reid’s History) as the best photograph in the show; in 1863, a review of the Photographic Society exhibition in London described Annan’s landscapes, which included “Loch Ranza,” “Ben Venue from Loch Achray,” “Waterfall at Inversnaid,” and “Aberfoyle,” as of such “great photographic excellence and high artistic merit” that “from this time forth he must rank amongst our first class artists”; in 1864, a large photograph of Dumbarton Castle was awarded a silver medal as “the best landscape in Scotland” by the Photographic Society of Scotland and was lavishly praised in The Photographic Journal on 15 April of the following year; and in 1865, Photographic News noted his “deep and poetic feeling and strong appreciation of the beautiful.” (Fig. 4:13) One scholar of our own time recently judged Annan “arguably the finest Scottish landscape photographer of the Victorian period.” In the view of another, “Annan’s landscapes, once highly regarded, should be highly regarded again.”47

10Still, whatever his artistic talent and inclination, photography was in the first instance Annan’s business and his livelihood. Not surprisingly, therefore, his first major photographic album, Views on the Line of the Loch Katrine Water Works (1859), was the result of a commission from “the Water Committee” of the Town Council or Corporation of Glasgow. It consisted almost exclusively of images of landscapes traversed by a massive engineering project — an extensive system of dams, sluices and siphon pipes constructed at various points around the famous loch and connected to a chain of aqueducts and tunnels — that the Corporation had undertaken in order to bring fifty million gallons of fresh water daily to the city 35 miles to the south and that had taken three and a half years to complete.

- 48 Quoted from the 1889 edition of Photographic Views of Loch Katrine and of some of the principal wor (...)

11Over the years, as the population of Glasgow continued to grow at a vertiginous rate and the Loch Katrine project was further expanded, this first and extraordinarily rare album of Annan’s was reproduced and amplified with new photographs, in 1877 and again in 1889, as Photographic Views of Loch Katrine, and of some of the principal works constructed for introducing the water of Loch Katrine into the city of Glasgow. These expanded albums, still produced in extremely limited numbers, were undertaken, in the words of the 1877 Preface, “at the suggestion of the Hon. James Bain, Lord Provost [i. e. Lord Mayor], to enable the members [of the Water Committee] to better understand the nature and extent of the works which supply the City with Water, and which have cost about two millions sterling; and thereby to assist them in controlling the details of the management of so necessary an element to a population which now approaches three quarters of a million.”48

12Annan’s albums also included a few Romantic images of scenes immortalized by The Lady of the Lake; the final photograph is of a fountain built in a Glasgow city park to commemorate the opening of the waterworks and topped by a bronze female figure of Ellen, the heroine of Scott’s poetic narrative. In contrast to the albums of Talbot and Wilson, however, or the many paintings of Loch Katrine by Scottish artists, or, for that matter, the earlier Turner painting of 1832 and its often reproduced engraved versions — all of which celebrate a scene that, thanks to Scott, had become emblematic of rugged, unspoiled nature (Figs. 4:14-18)— Annan’s reminders of the Romantic vision of the loch (Fig. 4:19) have the effect of highlighting the intrusion of modernity, in the form of a spectacular engineering project, into the famously primitive environment.

13At a banquet given in his honor in 1860, John Frederick Bateman, the chief engineer of the project, who had experience designing and building other city water supplies, himself noted the stark contrast between, on the one hand, the scale and modernity of the project, together with the engineering skill required to execute it, and, on the other, the beauty and isolation of the countryside in which the construction had been carried out.

- 49 Ibid., p. 9. The contrast between the traditional view of Loch Katrine, evoked by Annan himself in (...)

My merit is that of seeing my way more clearly through the rugged country that guards the peaceful bosom of Loch Katrine from the too familiar approach of man, and in determining at once what I believe to be the best and only practicable method by which the water could have been conveyed. It is impossible to convey to those who have not personally inspected it, an impression of the intricacy of the wild and beautiful district through which the Aqueduct passes for the first ten or eleven miles after leaving Loch Katrine. […] The country consists of successive ridges of the most obdurate rock, separated by deep, wild valleys, in which it was very difficult, in the first instance, to find a way. There were no roads, no houses, no building materials, nothing which would ordinarily be considered essential to the successful completion of a great engineering work for the conveyance of water; but it was a consideration of the geological character of the material which gave all the romantic wildness to the district, which at once determined me to adopt that particular mode of construction that has been carried out.49

14Annan’s photographs communicate vividly the striking juxtaposition of untamed nature and modern planning for an urban community (Figs. 4:20-21).

- 50 Ray McKenzie, “Thomas Annan and the Scottish Landscape: Among the Gray Edifices,” British Journal o (...)

- 51 Reported in Illustrated London News (22 October 1859), p. 404.

15In this respect, Ray McKenzie has observed, Views on the Line of the Loch Katrine Water Works, “as a landscape debut by a still comparatively inexperienced photographer is a work of great maturity and assurance” and “one of the key landscape statements of the period.”50 Whereas the countryside was generally viewed by the well-to-do of the nineteenth century as a healthy refuge from the more and more densely-populated, polluted and diseaseridden cities, Annan’s landscapes illustrated how a major work of modern engineering placed the pristine purity of a remote and wild countryside, extolled in Romantic literature, at the service of a huge, ever-growing urban population. In the words of the address by the Secretary to the Waterworks Commissioners at the official opening by Queen Victoria on October 14, 1859, the Loch Katrine Waterworks was “a great public work — alike important to the social and domestic comfort and enjoyment of the numerous inhabitants of the city of Glasgow, whose interests are entrusted to our management, as of incalculable benefit to many branches of manufacturing and commercial industry in the city and neighbourhood.”51

16Annan’s images also highlight the civic character of the enterprise, the role played in initiating and sustaining it by Glasgow’s elected officials and by the members of the Water Committee, representing the wards of the ceaselessly expanding city. In several photographs, the “water commissioners” and the Lord Provost are shown as a group, sometimes in the landscape, sometimes gathered together in front of a significant engineering feature of the project, their city clothes clashing incongruously with the natural environment (Figs. 4:22-24). In the closing words of the Preface, “The book is meant to be a record of a work which, among the many large and successful enterprises of the Town Council of Glasgow, is pre-eminently the most extensive and beneficial of them all. Among the works, both ancient and modern, for the supply of water to the large cities of the world, it is acknowledged to hold a prominent place, both as regards the purity of the water, the large quantity available, and the small cost at which it is delivered to the inhabitants.” It was, as the Secretary noted in his speech to the Queen, “one of the most interesting and difficult works of engineering and at the same the largest and most comprehensive scheme for the supply of water which has yet been accomplished in your Majesty’s dominions.” Along with Annan’s photographs, it was probably chief engineer Bateman who, in an address to the town councillors, underlined most effectively the modernity of the Loch Katrine water scheme, its immense distance from the Romantic old clan world of Scott’s poem — and from the numerous landscape photographs that aimed to confirm and propagate that Romantic vision of a pre-modern, pre-industrial world.

- 52 Photographic Views of Loch Katrine and of some of the principal works constructed for introducing t (...)

I leave you a work which I believe will, with very slight attention, remain perfect for ages, which, for the greater part of it, is as indestructible as the hills through which it has been carried, — a truly Roman work; not executed like the colossal monuments of the East by forced labour, at the command of an arbitrary sovereign, but by the free will and contributions of a highly civilized and enlightened city, and by the free labour of a free country. It is a work which surpasses the nine famous aqueducts which fed the city of Rome; and among the works of ornament or usefulness for which your City is now distinguished and will hereafter be famous none, I will venture to say, will be more creditable to your wisdom, more worthy of your liberality, or more beneficial in its results, than the Loch Katrine Water Works.52

17Though George Washington Wilson’s Trossachs and Loch Katrine appeared in a first edition seven years after the completion of the remarkable engineering project that Annan’s images had memorialized and that had been widely reported in the press (handsome engravings made from Annan’s photographs illustrated major articles in the London Illustrated News for 15 and 22 October 1859 [Figs. 4:25-26]), Wilson sedulously avoided any hint of the intrusion of modernity into the Romantic landscape defined by Scott’s Lady of the Lake (Figs. 4:27-28). The James Valentine firm followed suit: a view of Loch Katrine in a photograph of 1878 was carefully identified as that from the watchtower of Roderick Dhu, one of the heroes of Scott’s poem (Fig. 4:29).

18Likewise, in Queen Victoria’s journals, Scotland’s remote highlands and lochs continued to stand for a refuge from modernity, an admired ancient world, which she repeatedly associated with the works of Scott and unconsciously contrasted, by means of an allusion to the weather, with the world represented by the Loch Katrine Waterworks:

- 53 Queen Victoria, Our Life in the Highlands, selected from Leaves from the Journal of our Life in the (...)

Leaving this little loch to our left, in a few minutes we came upon Loch Katrine, which was seen at its greatest beauty in the fine evening light. Most lovely! We stopped at Stronachlachar, a small inn where people stay for a night sometimes, and where they embark coming from Loch Lomond and vice versa. As the small steamer had not yet arrived, we had to wait for about a quarter of an hour.

But there was no crowd, no trouble or annoyance, and during the whole of our drive nothing could be quieter or more agreeable. Hardly a creature did we meet, and we passed merely a very few pretty gentlemen’s places, or very poor cottages with simple women and barefooted, long-haired lassies and children, quiet and unassuming old men and labourers.

This solitude, the romance and wild loveliness of everything here, the absence of hotels and beggars, the independent simple people, who all speak Gaelic here, all make beloved Scotland the proudest, finest country in the world. [...] It was about ten minutes past five when we went on board the very clean little steamer Rob Roy — the very same we had been on under such different circumstances in 1859 on the 14th of October, in dreadful weather, thick mist and heavy rain, when my beloved husband and I opened the Glasgow Waterworks.53

4:1 “Château de Dunderaw sur le Lac Fine,” from François-Alexandre Pernot and Amédée Pichot, Vues pittoresques de l’Écosse (Paris: Charles Gosselin et Lami-Denozan, 1826; Brussels: A. Wahlen, A. Dewasme, 1827). Courtesy of Ancestry Images.

4:2 D.O. Hill, “Drumlanrig Castle,” from The Land of Burns (Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1840), vol. 2, facing p. 20.

4:3 John Fleming, “Loch Maree,” from Select Views of the Lakes of Scotland: from Original Paintings by John Fleming engraved by Joseph Swan; with historical and descriptive illustrations by John M. Leighton (Glasgow: J. Swan, [1834-1840]). Princeton University Library.

4:4 “The Saltmarket,” from James Pagan, Sketch of the History of Glasgow (Glasgow: Robert Stuart, 1847), facing p. 161; originally plate 20 of “Illustrated Letterpaper comprising a Series of Views in Glasgow” (Glasgow: Allen and Ferguson, 1843).

4:5 Thomas Annan, “Stonebyres Linn,” from his Photographs of the Clyde (Glasgow: Andrew Duthie, 1867). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:6 Thomas Annan, “Hamilton Palace,” from his Photographs of the Clyde. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:7 Thomas Annan, “Bothwell Castle,” from his Photographs of the Clyde. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:8 Thomas Annan, “Castle, Little Cumbray,” from John Eaton Reid, History of the County of Bute and Families connected therewith (Glasgow: T. Murray and Son, 1864). British Library, London.

4:10 Thomas Annan, “Tomb, St. Mary’s Chapel, Rothesay,” from History of the County of Bute. British Library, London.

4:13 Thomas Annan, “Dumbarton Castle.” Exhibited 1864. ©CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collection: The Mitchell Library, Special Collections.

4:15 W. Miller, “Loch Katrine,” engraving by W. Miller after the painting by J. M. W. Turner. Published in The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. (Edinburgh: Robert Cadell & Whittaker, 1833-34). Wikimedia.

4:16 William Henry Fox Talbot, “Loch Katrine,” from H. Fox Talbot, Esq., F. R. S., Sun Pictures in Scotland (London: [n. pub.], 1845), Plate 16. Salted paper print. Division of Rare Books, Marquand Library, Princeton University.

4:17 Alexander Nasmyth, “Landscape, Loch Katrine.” 1862. Oil on canvas. Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow. Courtesy of Glasgow Museums Collection.

4:18 Horatio McCulloch, “Loch Katrine.” 1866. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council.

4:19 Thomas Annan, “Loch Katrine and Ellen’s Isle and Ben Venue,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Photographic Views of Loch Katrine, and of some of the principal works constituted for introducing the water of Loch Katrine into the city of Glasgow (Glasgow: Printed by James C. Erskine, 1889). Albumen print. (Original photograph, 1859). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:20 Thomas Annan, “Aqueduct Bridge near Duntreath Castle, 22 miles from Loch Katrine,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. (Original photograph, 1859). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:21 Thomas Annan, “Endrick Valley looking South,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. (Original photograph, 1859). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:22 Thomas Annan, “Glasgow Corporation Water Commissioners at Loch Katrine, 1886,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:23 Thomas Annan, “Glasgow Water Commissioners at Loch Katrine, 1878,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:24 Thomas Annan, “Glasgow Water Commissioners at opening of a new aqueduct, 1886,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

4:25 Engraving from a photograph by Annan in Illustrated London News, 15 October 1859. Princeton University Library.

4:26 “Views of the Loch Katrine water works,” Illustrated London News, 22 October 1859. Princeton University Library.

4:27 George Washington Wilson, “Loch Katrine. The Silver Strand,” from Photographs of English and Scottish Scenery, vol. 11 (Aberdeen: Printed by John Duffus, 1865-1868). Albumen print.

4:28 George Washington Wilson, “Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine.” 1870s. Albumen print. Smith College Art Museum, SC 1982-38-565.

Anmerkungen

42 See Ray McKenzie, “A Love Affair with Loch Katrine: Problems of Representation in Early Scottish Landscape,” Scottish Photography Bulletin, 1 (1990), 3-12 (pp. 3, 5-7). Of the 23 photographs in Talbot’s Sun Pictures in Scotland, seven are devoted to Loch Katrine, the others to Abbotsford, Melrose, Dryburgh, the Scott Monument in Edinburgh and other scenes connected with Scott’s life and work.

43 See Smith, “Joseph Swan (1796-1872) engraver and publisher,” p. 92. Some of the photographs of landscapes in works by Annan, such as Photographs of the Clyde (Glasgow: Andrew Duthie, 1867) and Photographs of Glasgow (Glasgow: T.&R. Annan,1868), are in fact of subjects featured in Swan’s Select Views on the River Clyde, engraved by Joseph Swan from drawings by J. Fleming, with historical and descriptive illustrations by John M. Leighton (Glasgow: Joseph Swan, 1830) and Select Views of Glasgow and its Environs, engraved by Joseph Swan from drawings by Mr. J. Fleming and Mr. J. Knox, with historical and descriptive illustrations and an introductory sketch of the progress of the city by John M, Leighton, Esq. (Glasgow: Joseph Swan, 1828).

44 Thus, for example, Select Views of Glasgow and its Environs (see note 43 above); The Lakes of Scotland: A Series of Views from paintings taken expressly for the work by John Fleming, with historical and descriptive illustrations by John M. Leighton and remarks on the character of the Highland Scenery of Scotland by John Wilson (Glasgow: Joseph Swan, 1834); The Poetical Works of the Ettrick Shepherd [James Hogg] with an Autobiography and Illustrative Engravings, chiefly from Original Drawings by D.O. Hill, R.S.A. (Glasgow: Blackie and Son, [1838]), 5 vols.; The Land of Burns: A Series of Landscapes and Portraits illustrative of the life and writings of the Scottish poet by Professor John Wilson of the University of Edinburgh and Robert Chambers, Esq. The Landscapes from Paintings made expressly for the Work by D.O. Hill, Esq., R.S.A. (Glasgow: Blackie and Sons, 1840).

45 Ray McKenzie, “Thomas Annan and the Scottish Landscape: Among the Gray Edifices,” British Journal of Photography, 120 (12 October 1973), 40-49 (p. 42). For an overview of Annan’s many landscape photographs, see the thumbnails in the online inventory of the extensive holdings of Annan photographs at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow: http://www.rls.org.uk/database/results.php?search_term=annan&x=26&y=7 on pp. 8-83. Unfortunately, they cannot be enlarged.

46 The 1857 and 1860 editions, from different Glasgow publishers, appear not to have included illustrations. In all of Annan’s book publications, the photographs were still pasted in rather than printed along with the text. That possibility was not yet available in his time. Editions were therefore still restricted in number and copies expensive, but Annan was quick to realize the possibilities of the illustrated book. See on this topic Tom Normand, “The Book as Photography,” in The Edinburgh History of the Book in Scotland, ed. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery, vol. 4 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), pp. 168-81.

47 Ray McKenzie, “Landscape in Scotland: Photography and the Poetics of Place,” in Light from the Dark Room: A Celebration of Scottish Photography, ed. Sara Stevenson (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1995), p. 76; William Buchanan, entry on “Annan, Thomas,” in John Hannavy, ed., Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, vol. 1, pp. 44-47. Journal passages cited in William Buchanan, “The Annans of Glasgow,” Studies in Photography (2006), 21.

48 Quoted from the 1889 edition of Photographic Views of Loch Katrine and of some of the principal works constructed for introducing the water of Loch Katrine into the city of Glasgow by T.& R. Annan and Sons, with descriptive notes by James M. Gale, M. Inst., C.E., Engineer to the Commissioners (Glasgow: Printed by James C. Erskine). The earlier edition of 1877 (Glasgow: McLaren and Erskine) is held by the National Library of Scotland, the library of the Glasgow School of Art, the Library of Congress, the George Eastman House Museum, the library of the University of Guelph in Canada and the British Art Center at Yale. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the only accessible copy of the original 1859 album is held by the Mitchell Library of Glasgow.

49 Ibid., p. 9. The contrast between the traditional view of Loch Katrine, evoked by Annan himself in his album, and that presented by the photographs in Views on the Line of Loch Katrine Water Works is noted by Rachel Stuhlman in her article “‘Let Glasgow Flourish’: Thomas Annan and the Glasgow Corporation Waterworks,” p. 43.

50 Ray McKenzie, “Thomas Annan and the Scottish Landscape: Among the Gray Edifices,” British Journal of Photography (12 October 1973), p. 42.

51 Reported in Illustrated London News (22 October 1859), p. 404.

52 Photographic Views of Loch Katrine and of some of the principal works constructed for introducing the water of Loch Katrine into the city of Glasgow (as in endnote 48 above), p. 20. On Annan’s Photographic Views of Loch Katrine as a “testament to the continuing will for civic improvement,” see Stuhlman, “‘Let Glasgow Flourish,’” p. 43. Growing up in Glasgow in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, the author of this essay remembers how much pride the citizens continued to take in their city’s water — purer, they were convinced, than that of any other large city in the world. Bottled spring water was unheard of and, if it had been known, it would have been pronounced inferior.

53 Queen Victoria, Our Life in the Highlands, selected from Leaves from the Journal of our Life in the Highlands [London: Smith, Elder, 1868] and More Leaves from the Journal of a Life in the Highlands. [London: Smith, Elder, 1884] (London: William Kimber, 1968), pp. 129-30 (entry for Thursday, 2 September 1869). Queen Victoria seems not to have felt that the “steamer” she referred to was not exactly in harmony with the antique simplicity she so appreciated. A similar, even more striking unawareness is displayed in a report on a journey to Scotland undertaken by the well-known German art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen in 1850: “By a happy combination of steamboat, railway and pedestrian journeys we managed to see Loch Lomond and Loch Long [...] in one day. Never before had I witnessed scenery which bore so strongly the impress of a grand melancholy. In those mists which never dispersed during the whole day, and veiled more or less the forms of the hills, I could well imagine the presence of those Ossianic spirits which pervade Macpherson’s poems. Many parts also brought Scott’s ‘Lady of the Lake’ vividly before me.” (Cit. James Holloway and Lindsay Errington, The Discovery of Scotland: The Appreciation of Scottish Scenery through Two Centuries of Painting [Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1978], p. 103). Holloway and Errington note that “Waagen’s discrepant experience, the incongruity of which he seems not to have noticed, was matched by that of thousands of other nineteenth-century tourists who were enabled by the newly engineered communications systems to reach in easy journeys the most remote of Highland lochs and glens, but who, their goal attained, blotted the presence of steamboat, coach, and train from their vision and looked only for Ossian and Scott.” Some, however, were keenly aware that the invasion of modernity undermined the Romantic view of Scotland. Lord Cockburn complained in 1844 that “from Edinburgh to Inverness the [...] country is an asylum of railway lunatics [...]. And anyone who puts in a word for the preservation of scenery, or relics, or ancient haunts, is put down as hostile [...] to ‘modern improvement’ and the ‘march of intellect’.” The railways, he protested, annihilated the scenic beauty they were designed to render available. “I never see a scene of Scotch beauty without being thankful that I have beheld it before it has been breathed over by the angel of mechanical destruction.” (Cit. ibid.)

Abbildungsverzeichnis

| |

|---|---|

| Bildunterschrift | 4:1 “Château de Dunderaw sur le Lac Fine,” from François-Alexandre Pernot and Amédée Pichot, Vues pittoresques de l’Écosse (Paris: Charles Gosselin et Lami-Denozan, 1826; Brussels: A. Wahlen, A. Dewasme, 1827). Courtesy of Ancestry Images. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-1.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 12k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:2 D.O. Hill, “Drumlanrig Castle,” from The Land of Burns (Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1840), vol. 2, facing p. 20. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-2.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:3 John Fleming, “Loch Maree,” from Select Views of the Lakes of Scotland: from Original Paintings by John Fleming engraved by Joseph Swan; with historical and descriptive illustrations by John M. Leighton (Glasgow: J. Swan, [1834-1840]). Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-3.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:4 “The Saltmarket,” from James Pagan, Sketch of the History of Glasgow (Glasgow: Robert Stuart, 1847), facing p. 161; originally plate 20 of “Illustrated Letterpaper comprising a Series of Views in Glasgow” (Glasgow: Allen and Ferguson, 1843). |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-4.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:5 Thomas Annan, “Stonebyres Linn,” from his Photographs of the Clyde (Glasgow: Andrew Duthie, 1867). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-5.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 20k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:6 Thomas Annan, “Hamilton Palace,” from his Photographs of the Clyde. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-6.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:7 Thomas Annan, “Bothwell Castle,” from his Photographs of the Clyde. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-7.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 32k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:8 Thomas Annan, “Castle, Little Cumbray,” from John Eaton Reid, History of the County of Bute and Families connected therewith (Glasgow: T. Murray and Son, 1864). British Library, London. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-8.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:9 Thomas Annan, “Loch Ranza Castle,” from History of the County of Bute. British Library, London. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-9.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 12k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:10 Thomas Annan, “Tomb, St. Mary’s Chapel, Rothesay,” from History of the County of Bute. British Library, London. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-10.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 20k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:11 John Knox, “The Head of Glen Sannox.” Oil on canvas. Wikimedia. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-11.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 12k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:12 Thomas Annan, “Glen Sannox,” from History of the County of Bute. British Library, London. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-12.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:13 Thomas Annan, “Dumbarton Castle.” Exhibited 1864. ©CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collection: The Mitchell Library, Special Collections. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-13.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 24k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:14 John Knox, “Landscape with tourists at Loch Katrine.” Ca. 1820. Oil on canvas. Wikimedia. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-14.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 8,0k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:15 W. Miller, “Loch Katrine,” engraving by W. Miller after the painting by J. M. W. Turner. Published in The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. (Edinburgh: Robert Cadell & Whittaker, 1833-34). Wikimedia. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-15.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 12k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:16 William Henry Fox Talbot, “Loch Katrine,” from H. Fox Talbot, Esq., F. R. S., Sun Pictures in Scotland (London: [n. pub.], 1845), Plate 16. Salted paper print. Division of Rare Books, Marquand Library, Princeton University. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-16.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:17 Alexander Nasmyth, “Landscape, Loch Katrine.” 1862. Oil on canvas. Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow. Courtesy of Glasgow Museums Collection. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-17.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 12k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:18 Horatio McCulloch, “Loch Katrine.” 1866. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-18.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 24k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:19 Thomas Annan, “Loch Katrine and Ellen’s Isle and Ben Venue,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Photographic Views of Loch Katrine, and of some of the principal works constituted for introducing the water of Loch Katrine into the city of Glasgow (Glasgow: Printed by James C. Erskine, 1889). Albumen print. (Original photograph, 1859). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-19.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 24k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:20 Thomas Annan, “Aqueduct Bridge near Duntreath Castle, 22 miles from Loch Katrine,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. (Original photograph, 1859). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-20.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 24k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:21 Thomas Annan, “Endrick Valley looking South,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. (Original photograph, 1859). Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-21.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 24k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:22 Thomas Annan, “Glasgow Corporation Water Commissioners at Loch Katrine, 1886,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-22.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 32k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:23 Thomas Annan, “Glasgow Water Commissioners at Loch Katrine, 1878,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-23.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 36k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:24 Thomas Annan, “Glasgow Water Commissioners at opening of a new aqueduct, 1886,” from Glasgow Corporation Water Works. Albumen print. Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-24.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 28k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:25 Engraving from a photograph by Annan in Illustrated London News, 15 October 1859. Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-25.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 36k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:26 “Views of the Loch Katrine water works,” Illustrated London News, 22 October 1859. Princeton University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-26.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 56k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:27 George Washington Wilson, “Loch Katrine. The Silver Strand,” from Photographs of English and Scottish Scenery, vol. 11 (Aberdeen: Printed by John Duffus, 1865-1868). Albumen print. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-27.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 12k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:28 George Washington Wilson, “Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine.” 1870s. Albumen print. Smith College Art Museum, SC 1982-38-565. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-28.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 16k |

| |

| Bildunterschrift | 4:29 James Valentine, “Loch Katrine. Trossachs from Roderick Dhu’s Watch Tower.” 1878. Gelatin dry plate negative. St. Andrews University Photographic Collection, JV-270. A. Courtesy of St. Andrews University Library. |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/obp/docannexe/image/2547/img-29.jpg |

| Datei | image/jpeg, 20k |

Nur der Text ist unter der Lizenz CC BY 4.0 nutzbar. Alle anderen Elemente (Abbildungen, importierte Anhänge) sind „Alle Rechte vorbehalten“, sofern nicht anders angegeben.