Les arts de la couleur en Grèce ancienne… et ailleurs

|Arts polychromes et dorés, synthèses et études de cas

The Painted Decoration on the Garment of the Nikandre Statue

Le décor peint sur la robe de la statue de Nikandrè

Ο γραπτός διάκοσμος του ενδύματος του αγάλματος της Νικάνδρης

Abstract

Already in 1882, in the presentation of the Nikandre statue in the Archäologische Zeitung by A. Furtwängler, mention was made of the existence of painted decoration on the garment of the figure. The author speaks specifically of seven to eight wide bands of meander, the typical Greek motif, which can be discerned on the dress of the statue of Nikandre underneath the belt. Since then, no progress has been made on this matter; on the contrary, the decoration of the garment of the Nikandre statue has almost been forgotten. In the meantime, the well-preserved decoration of the dress of a number of female Daedalic statues has been adequately published, such as that of the Lady of Auxerre and of the seated statue of Gortyna. A new study of the Nikandre statue has revealed some engraved motifs, which, with the help of these parallels, throw new light on this matter and allow us to reconstruct with more certainty the painted decoration of the dress of the Nikandre statue.

Termini per la ricerca

Mots-clés :

Délos, Nikandrè, Dame d’Auxerre, statues féminines dédaliques, robes, incisions, méandre, GortyneΛέξεις-κλειδιά :

Δήλος, Νικάνδρη, κυρία της Ωξέρ, γυναικείες δαιδαλικές μορφές, ένδυμα, εγχάρακτα μοτίβα, μαίανδρος, ΓόρτυναTesto integrale

I would like to thank the organisers of this very interesting conference, especially Professor P. Jockey, for inviting me to participate. Furthermore, I thank my friend Ms E. Walter-Karydi for her encouragement to present my research on the decoration of the kore of Nikandre at this symposium, and Professor G. Despinis for the fruitful discussions that we had on this very topic. See G. Despinis, N. Kaltsas (eds), Κατάλογος Γλυπτών Ι.1. Γλυπτά των Αρχαϊκών Χρόνων από τον 7ο αιώνα έως το 480 π. Χ (2014). I also thank Ms A. Antonakos for the translation of my Greek text into English, Professor Pl. Petridis for the translation of the summary into French and Ms A. Drigkopoulou for the drawings of the statue of Nikandre, figs. 10-11, 17. I am also grateful to Dr K. Karakasi for providing me with the photos in figs. 1, 3-5, 8. Professor Dr N. Kourou for the photos in figs. 14-15, the Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Crete and M. Koutsoumbou for the photos in figs. 6-7, 12-13, the Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge for the photo in fig. 18, and Dr J.-L. Martinez for the photo in fig. 5.

- 1 A. Furtwängler, “Von Delos”, AZ 1882, p. 322. See P. Kavvadias, Γλυπτά του Εθνικού Μουσείου. Κατάλο (...)

- 2 J. Marcadé, “La pélerine de l’Artémis de Nikandré”, in J. Servais, T. Hackens, B. Servais-Soyez (ed (...)

1The statue that the aristocratic Naxian woman Nikandre dedicated at the sanctuary of Artemis on Delos is very well known, and has been much discussed by scholars (fig. 1). What has not been especially emphasized and sufficiently clarified up to now is the fact that this statue, the oldest surviving marble statue of a kore of natural size, also displays painted decoration. In fact, it is strange that, even though A. Furtwängler explicitly referred to the existence of remnants of coloured decoration in 1882,1 this was in time forgotten and ignored or in any case not mentioned. But recently attention has once again been paid to the existence of colour, although without a new study, which would add to our knowledge about certain details and would give a fuller picture of the decorative motifs of the garment as well as the colours that were used.2 However, during the thorough re-examination of the statue undertaken when compiling an academic catalogue of sculptures in the National Archaeological Museum, supervised by Professor Emeritus G. Despinis and the museum’s director N. Kaltsas, I focused intensively on the painted decoration of this statue’s garment. Not only were traces of painted decorative bands observed, but the incised outlines of decorative motifs arranged in bands on the garment were also detected, albeit with great effort and difficulty. Furthermore, there was decoration on the belt that holds the garment at the waist.

- 3 Frequently, one of its sides, usually the right, remained open, with the leftover cloth creating th (...)

- 4 Sometimes the peplos had a long and sometimes a short overfold (apoptygma), sometimes it was belted (...)

2Nevertheless, before we systematically examine all these new data, some things must be said about the garment of the Nikandre statue itself. It is of the kind usually found on Daedalic statues, statuettes and clay figurines of korai of the 7th century BC. It is a foldless garment reaching to the feet that is supported at the waist by a wide belt and possibly sewn without an open side, since there is no evidence of an opening anywhere. The absence of folds and the invisibility of the body beneath the garment led researchers to identify it with the Doric peplos. The peplos (fig. 2) was a large rectangular piece of thick woollen fabric, which was fastened only by pins or fibulae on the shoulders and with a belt at the waist.3 The peplos was always characterized, in the 6th century and during the Classical and subsequent periods, by the overfold (apoptygma): the folding of the fabric on the upper torso, which was related to its length, as well as to the height of the female or youthful figure that wore it.4

- 5 For a detailed description see G. Kokkorou-Alevras in G. Despinis, N. Kaltsas (eds), Κατάλογος Γλυπ (...)

- 6 Folds only just start to appear during the second quarter of the 6th century BC on both female and (...)

3The garment worn by the female figure of Nikandre appears thick, as peploi usually are (at least during the early years), although it does not have any of the other features of the garment known as the peplos. Thus, the overfold (apoptygma) is missing, while the cape (epiblema) covers the figure’s shoulders and therefore we cannot discern to what degree pins or fibulae, which would have held the garment together if it was a peplos, were present there. In addition, sleeves (cheirides) are not visible on the figure’s hands, which would be necessary if the garment were a chiton. Only the end of the cape, which is as a rule worn by female figures of the Daedalic period, is visible at the rear side of the right hand. This is due partly to the intensive weathering of the statue’s skin but mainly to the reworking of the surface of the arms and forearms, which is attested by the traces of flat chiselling visible on these points.5 Finally, the absence of folds should be attributed to the early date of the statue, that is, to the Daedalic years of its creation, during which time folding of garments was not rendered. Nevertheless, the possibility that the garment was actually made of a thick woollen fabric cannot be excluded.6

Fig. 1 — Statue of Nikandre. Front view.

(Photo: K. Kontos.)

Fig. 2 — Archaic garments of korai.

(After J. Boardman, Ελληνική Πλαστική. Αρχαϊκή Περίοδος [trans. E. Simantoni-Bournia, 1982], p. 82.)

- 7 M. Bieber (n. 3, 1973), p. 431; A. Pekridou-Gorecki (n. 3), pp. 72-77.

- 8 It is not unlikely that the chiton was sewn out of a single piece of fabric: see n. 20 below. The p (...)

- 9 See n. 12.

4On the other hand, the garment known as the chiton consisted of two7 rectangular pieces of fabric, the two vertical sides of which were sewn to form a cylinder, which women wore without an overfold, at least in the early and Archaic periods.8 The belt was also a necessary piece of the chiton to hold the garment in place, while some of its characteristic features include the sleeves, that were formed either with buttons or with a stitch, and the kolpos, which varied in length and width. Taken as a whole, female statuettes of the 7th century9 wear a sewn garment that reaches to the feet with short sleeves, without an overfold and with no indication of folding of any kind, as has already been mentioned. The lack of folds, however, could possibly be a chronological and not a typological element, which could help us to identify the garment as one type or another, given that, even on the peplos, folds are formed at least from the Classical period onwards, although they are certainly sparser and wider.

- 10 See Davaras 1972, pp. 26 -27, figs. 1-7, 9-10, 50-56; J. Floren, Die grieschische Plastik I (1987), (...)

- 11 For example, the terracotta statuettes: Richter 1968, pp. 33-34, nos. 23-27, figs. 86-102: second h (...)

- 12 B. Schmaltz (n. 11), p. 10.

- 13 Indeed, if we exclude the female figures of the Triad of Dreros (Richter 1968, p. 32, nos. 16-17, f (...)

- 14 H. Kyrieleis, “Holzfunde aus Samos”, AM 95 (1980), pp. 97-98.

5All these features show that the female figure represented in the dedication of Nikandre, most likely the goddess Artemis, is wearing a chiton and not a peplos –or, at least, is a type of garment more similar to the chiton of the 6th century BC. Other Daedalic female figures also wear this garment, such as the Lady of Auxerre (figs. 3-5), the goddesses of Prinias (figs. 6-7), the goddess from Astritsi and so on,10 as do Daedalic figures on clay plaques or figurines of korai from the Daedalic period, on some of which sleeves are clearly visible.11 The same view, that Nikandre’s Artemis is wearing a chiton, has been set out by B. Schmaltz in his recent study of the representation of the peplos on female painted and sculpted figures, in which he refers to even more examples of female figures of the 7th century who wear a chiton.12 The suggestion of E. Harrison, recently followed by G. Kaminski, that the cape (epiblema) is not a separate garment on female Daedalic figures, but that they wear a uniform garment, a chiton or peplos, the rear side of which is drawn over the shoulders and fastened in front of the chest with pins or fibulae, seems unlikely and, moreover, not practical at all. The reason for this is that the rear side of the dress, according to this hypothesis, would have to be longer than the front, while compensating for this asymmetry would require the creation of a kolpos to cover the belt in the front view, which does not occur in female Daedalic figurines and statues.13 Conversely, H. Kyrieleis argues for the existence of a cape already in Minoan female dress, and specifically on the sarcophagus of Hagia Triada.14

- 15 On the garment of perirranterion korai see M. Sturgeon, Isthmia IV. Sculpture I: 1952-1967 (1987), (...)

6The same garment, that is, the chiton with short sleeves, although without the cape, is worn by the so-called perirrhanterion korai. M. Sturgeon also believes that many female figures of the 7th century wear this garment, and she identifies it with the Ionic chiton of Herodotus, also known as Carian.15

- 16 Raubitschek 1975, p. 50; Donohue 2005, pp. 216-218, figs. 34-37. Similar vertical incisions on the (...)

- 17 Above, n. 13.

- 18 For such fringes on Cretan garments see A. Lembessi, “Σχέσεις Σάμου και Κρήτης τον 7° αι.”, in N. C (...)

- 19 Sleeved chitons of statues of korai of the early 6th century, such as the kore in the Museum of Del (...)

- 20 In fact, it is very likely that this central decorative band was woven into one end of the fabric o (...)

- 21 Karakasi 2001, pll. 245, 238. Recently, V. Brinkmann, in V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13), pp. 53-5 (...)

- 22 See for example B. Schmaltz (n. 11), p. 5, figs. 1-2.

- 23 See Raubitschek 1975.

7Another characteristic element of the long (poderes) female garment of the 7th century, the chiton rather than the peplos, as already mentioned, is its decoration with a wide vertical band at the centre of the dress on the front as well as at the hem. As can be seen very clearly on the statuette of the Lady of Auxerre (figs. 3-5), the lower part of the garment, which today we could call the skirt, bears an incised decoration at the centre of its front consisting of a wide vertical band divided into rectangular decorative fields, metopes, which in turn are decorated with squares or rectangles. These incisions were surely the base on which ornaments were painted with vivid colours. At the hem of the garment of the Lady of Auxerre there is a wide band with incised decorations similar to the above which run all the way around the garment (figs. 3-5). However, beneath this hem vertical incisions are regularly spaced so as to give the impression of schematic folds, which led some researchers to hypothesize that there are two or even three dresses, together with the cape, on this statue and on other female Daedalic statues as well.16 V. Brinkmann considers this an ependytes, while Donohue believes it to be a kind of dress made out of a hard, rigid cloth which is reminiscent of the aprons of Thessalian women.17 However, this type of decoration is not found on all female Daedalic figures. It could be interpreted as the rendering of schematic folds at the end of the long dress or as a fringe.18 In any case, characteristic of the type of garment that interests us is the fact that even on korai of the 6th century, who are clearly wearing a sleeved chiton, there are similar decorative incised bands that were enlivened with colours (fig. 8).19 There are numerous examples of statues of korai, to which can be added even more contemporary figurines, that attest that ultimately this type of decoration was very closely connected with the garment called a chiton.20 However, the peplos of the well-known “Peplophoros” at the Acropolis of Athens (fig. 9), as well as those of the few other peplophoroi attested to in the Archaic period, are also decorated with a vertical band at the centre of the front that bears a painted meander or other type of decoration.21 This is also attested by Archaic peplophoroi on painted Archaic vases.22 Therefore, we must assume that all the fabrics for sewing female garments were woven with wide selvedges that bore linear-geometric designs or figurative representations of animals.23

Fig. 3 — Lady of Auxerre. Front view.

(After Karakasi 2001, pl. 53a.)

Fig. 4 — Lady of Auxerre. Left side view.

(After Karakasi 2001, pl. 53d.)

Fig. 5 — Lady of Auxerre.

(Drawing: I. Bradfer.)

Fig. 6 — Goddess of Prinias. Front view.

(Photo: Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Crete. © Ministry of Culture. TAP - Archaeological Receipts Fund)

Fig. 7 — Goddess of Prinias. Three quarter view from the left side of the statue.

(Photo: Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Crete. © Ministry of Culture. TAP - Archaeological Receipts Fund).

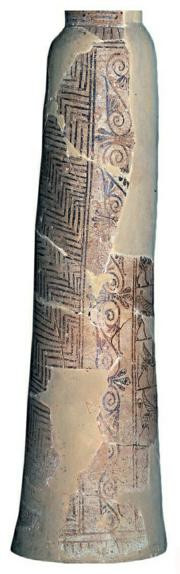

Fig. 8 — Kore. Museum of Delos A 4062.

(Photo: G. Karatzas.)

Fig. 9 — “Peplophoros”.

(After ArchEphem 1887.)

- 24 The collaboration of the conservator of the National Archaeological Museum, Ms D. Bika, and of the (...)

- 25 Unfortunately, in order for these methods to be used, full darkening of the area in which the statu (...)

8This conclusion corresponds in all respects to the other important finding that was mentioned at the beginning of this discussion. As already noted, in 1882 A. Furtwängler referred to traces of seven to eight painted bands bearing meanders lower than the belt of the statue of Nikandre, which certainly would have been visible in the years immediately after the statue’s discovery. However, even today three uneven but parallel bands are distinguishable in the right light, because of their lighter surface colour, as is usually the case with ancient sculpture when, at some point long after the creation of the statue, the colours that covered these surfaces are effaced (fig. 1). The existence of incised guidelines for the separation of these horizontal bands confirms our finding. The observation of all the decorations here presented was made possible after light sprinkling of the surface of the statue with water, under the light of a strong spotlight at a low angle, as well as through the use of a Leica stereomicroscope (maximum magnification 4.0x).24 The application of more conclusive and advanced methods such as ultraviolet fluorescence and ultraviolet reflection, even if they had been desirable, was not possible, for technical reasons.25 Using these methods, I was able to discover a wider band at the lower part of the garment with a width of 11-13 cm (figs. 10-11). Next, two thin incised lines 3.5 cm apart separate this band from the next band, which has a width of 8-10.5 cm. Two horizontal lines 1.5 cm apart, once again engraved, separate the second decorative band, which is clearly narrower than the lower one already mentioned, from the third even narrower horizontal decorative band 5-6.5 cm in width that follows.

- 26 Donohue 2005, pp. 216-218, fig. 42.

- 27 Maas 2002, pp. 65-67, fig. 136.

- 28 J. Boardman (n. 21), fig. 30; J. Floren (n. 10), pp. 125-126, pl. 7.1. Kaminski 2002, pp. 92-93, fi (...)

- 29 See n. 11 above. For a drawing of the new kore of Eleutherna see J.-L. Martinez (n. 10), p. 44, fig (...)

9The fact that these bands are parallel to one another and perfectly horizontal is noticeable. That is, they do not follow the semicircular edge –the hemline– of the garment, as would be expected if we assume that woven decorative bands are shown. This is possibly due to the fact that the craftsman who painted the decoration of the garment ignored this naturalistic element, which would point to the artistic freedom of the Archaic painter. According to Donohue,26 however, this may be because the painted bands constitute the decoration of another garment, perhaps a type of apron made of hard, inflexible fabric worn over the pleated chiton, whose folds would have been depicted with short vertical incisions, similar to those which are in fact visible at the lower end of the garment of the Lady of Auxerre (figs. 3-5). Unfortunately, I detected traces of a meander only in the lowest band, which would have been painted on the entire band (figs. 10-11). On the other two bands there are no visible details, that is, no traces of the decorative motifs that I assume were painted on these bands. Furthermore, on the dress of Nikandre’s Artemis there is no visible wide vertical central band, as there is on the garments of the seated goddess of Gortyna (figs. 12-13), the Lady of Auxerre (figs. 3-5), the seated goddesses of Prinias in Crete (figs. 6-7), and the hammered (sphyrelaton) statues from Olympia,27 but it is very possible that it was rendered with colour. The rendering of small rosettes in a vertical arrangement near the sides of the skirt of Nikandre’s Artemis is, on the other hand, certain (figs. 10-11). At least five incised rosettes were discovered on the left and two on the right, and they give the impression that they were arranged in vertical bands, columns, as occurs with the rosettes that also decorate vertical bands on either side of the wide central band on the seated goddess of Gortyna in the Museum of Heraklion (figs. 12-13).28 This motif, on the other hand, is missing from the Lady of Auxerre (figs. 3-5) and the new kore of Eleutherna, and also from the seated goddesses of Prinias (figs. 6-7).29

Fig. 10 — Drawing showing the traces of the decoration left on the dress of the statue of Nikandre.

(A. Drigkopoulou.)

Fig. 11 — Reconstruction of the painted decoration on the dress of the statue of Nikandre.

(A. Drigkopoulou.)

Fig. 12 — Goddess of Gortyna. Front view.

(Photo: Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Crete. © Ministry of Culture. TAP-Archaeological Receipts Fund.)

Fig. 13 — Goddess of Gortyna. 3/4 view of the left side.

(Photo: Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Crete. © Ministry of Culture. TAP-Archaeological Receipts Fund).

Fig. 14 — Figurine of Siphnos. Rear and right side view.

(Photo: M. Gkili-Kofinaki).

Fig. 15 — Figurine of Siphnos. Front view.

(Photo: M. Gkili-Kofinaki.)

- 30 J. Boardman, J. Dorig, W. Fuchs, Die griechische Kunst (1966), fig. 142.

- 31 N. Kourou, “Τα Είδωλα της Σίφνου. Από την Μεγάλη Θεά στην Πότνια Θηρών και στην Αρτέμιδα”, in Πρακτ (...)

- 32 E. Walter-Karydi, “Bronzes pariens et imagerie cycladique du haut archaïsme”, in Y. Kourayos, Fr. P(...)

- 33 Raubitschek 1975; H. Kyrieleis, “Archaische Holzfunde aus Samos”, AM 95 (1980), pp. 97-98; A. Lembe (...)

10The existence of one more decorative motif, a meander cross, which I discerned with even greater difficulty to the left of the column of rosettes (as the viewer faces it), shows that the guilloches (plochmoi) in the corresponding position on the seated statue of Gortyna (figs. 12-13) have been replaced on the statue of Nikandre by this motif, which most likely also was arranged in a vertical column. For symmetrical reasons, we must assume there was a corresponding vertical band on the left side of the kore’s skirt (figs. 10-11). These columns of ornamentation, in any case, would flank a central decorative band, on which the meanders that Furtwängler noted would have most likely been depicted. In fact, strong lighting from a low angle enabled us to discern traces of meander on the upper part of the central section of the skirt, and based on these I reconstructed meanders in zones on the vertical central decorative band in the drawing (fig. 11). This reconstruction is also based on Furtwängler’s information mentioned above, as well as on the garment of the daughters of Proetus, Lysippe and Iphianassa as depicted on the painted clay metope from Thermos (625 BC).30 Meander ornaments, moreover, decorate the skirt worn by the large-sized clay figurine from Siphnos which has been associated with Naxos (figs. 14-15).31 A meander ornament is also found on the garment of the sphyrelaton female figure from Olympia that E. Walter-Karydi has associated with Parian art.32 However, the connection of the decoration of the garment of the Nikandre kore in its general conception and structure with that of the seated goddess of Gortyna is obvious. This therefore confirms the Cretan origin, which has been generally accepted by scholars, of the female Daedalic garment, and possibly also of its decoration.33

- 34 J. Boardman, Excavations in Chios 1952-1955. Chios. Greek Emporio (1967), p. 63, pll. 88-90, especi (...)

- 35 Davaras 1972, pp. 18-19, figs. 23-24.

- 36 For the ways of fastening the belts on Cretan korai see Raubitschek 1975, pp. 49-52: figs. 4-5. See (...)

11The belt that holds the garment on the Artemis of Nikandre together also has painted decoration (figs. 10-11). Rectangular motifs are visible, which have been very badly preserved but quite likely belonged to the so-called battlement ornament. Similar bronze belts, dated by context to the 7th century, have actually been found as dedications at sanctuaries, such as those from the sanctuary of the harbour at Emporio on Chios that J. Boardman published. Even more interesting is the fact that these belts were decorated with ornaments –meanders, “guilloches” (plochmoi), and battlement ornaments– comparable to those painted on the belt of the Artemis of Nikandre.34 Furthermore, the belt of the statue of Gortyna, with a central buckle, is decorated with a painted continuous spiral (figs. 12-13).35 On Nikandre’s Artemis, however, there is no buckle to be seen on the belt, though it probably existed. Nevertheless, on the middle part of the belt and all along its length a type of band is formed on the marble surface that is darker than the parts above and below it, so that ultimately two lighter bands are visible both above and below, on which the battlement ornament was depicted. In fact, on the lower light-coloured band of the belt I noticed minor traces of red colour. This shows that there was another lighter colour, possibly yellow, on the middle part of the belt, but there is no indication of a buckle.36

- 37 See Donohue 2005, p. 139, fig. 19, where the hem of the cape with the incised decoration is more vi (...)

- 38 Davaras 1972, p. 26, fig. 38; Kaminski 2002, pp. 93-94, fig. 168.

12A decorative band with geometrical decoration, as known from the cape of the Lady of Auxerre,37 or with rosettes, as on the cape of the kore from Eleutherna,38 would have possibly decorated the selvedge of the cape of the Artemis of Nikandre. Today, however, nothing at all is visible due to severe weathering.

Fig. 16 — Traces of red colour on Nikandre.

(Photo: D. Bika.)

Fig. 17 — Coloured reconstruction of the painted decoration on the dress of the statue of Nikandre.

(A. Drigkopoulou.)

Fig. 18 — Coloured cast of the Lady of Auxerre.

(© Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge).

- 39 E.g. figurine of a mourning woman from Boeotia: J.-L. Martinez (n. 10), fig. 25, but also on a marb (...)

- 40 V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13), p. 33, pl. 33 (Berlin goddess); p. 182, fig. 326 (Phrasikleia).

- 41 See the Anavyssos kouros (N. Kaltsas, Το Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο [2007], pl. 240), Berlin godde (...)

- 42 For the light-coloured himation, see the Berlin goddess: V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13).

13Unfortunately, I was able to discern only a few traces of red colour on the lower right side of the kore’s skirt, much higher than the hemline (fig. 16), and on two more points, as mentioned, on the lower band of the belt. Nevertheless, it is most likely that the basic colours used in sculpture at this time were applied to the decoration of the garment of the kore of Nikandre (fig. 17): red for the chiton, as for example on many clay figurines of the 7th century,39 such as on the chiton of the “Berlin Goddess” and of Phrasikleia,40 and blue for the motifs themselves. The coloured representation of the Lady of Auxerre in the Cambridge cast is characteristic (fig. 18). Black would have been used to accentuate the locks of the hair and the lashes, red probably for the lips and the iris, and finally blue for the pupils of the eyes.41 Thus the general picture that would have emerged would have enlivened the statue and softened the sense of flatness that predominates today. With the artist A. Drigkopoulou, I attempted to reconstruct the painted decoration, conjecturally as regards the colours, but in a close approximation as far as the ornaments were concerned (fig. 17). In the coloured reconstruction, the chiton is red and all the ornaments are depicted in blue, while the middle section of the belt and the soles of the closed shoes are yellow. Also, based on the multi-coloured principle of ancient statues and the intense coloured contrasts, we adopted yellow for the background of the bands with the rosettes, as well as for the cape, in a manner analogous to the light-colored himation of the Berlin goddess.42 It is quite possible that this multi-coloured version approaches the spirit of the Daedalic and Archaic periods. Certainly, our reconstruction is experimental and hypothetical in character, but we do hope that it will serve as inspiration for further examination.

Addendum

14About the rests of red colour on the dress of the statue of Nikandre, see recently D. Βika, Μελέτη της πολυχρωμίας της αρχαϊκής γλυπτικής (Diss. Athens, 2015), pp. 218, 221, fig.. AK1-3.

Bibliografia

Bibliographical abbreviations

Bieber 1967 = M. Bieber, Entwicklungswgeschichte der griechischen Tracht.

Davaras 1972 = C. Davaras, “Die Statue aus Astritsi”, AntK Suppl. 8.

Donohue 2005 = A. A. Donohue, Greek Sculpture and the Problem of Description.

Kaminski 2002 = G. Kaminski, “Dädalische Plastik”, in P. C. Bol et al., Die Geschichte der antiken Bildhauerkunst I. Frühgriechische Plastik, pp. 71-95.

Karakasi 2001 = K. Karakasi, Archaische Koren.

Freyer-Schauenburg 1974 = B. Freyer-Schauenburg, Bildwerke der archaischen Zeit und des strengen Stils, Samos 11.

Maas 2002 = M. Maas, “Der orientalisierende Stil”, in P. C. Bol et al., Die Geschichte der antiken Bildhauerkunst I. Frühgriechische Plastik, pp. 45-69.

Meyer, Brüggemann 2007 = M. Meyer, N. Brüggemann, Kore und Kouros: Weihegaben für die Götter. Raubitschek 1975 = I. and T. Raubitschek, “Der kretische Gürtel”, in Wandlungen. Studien zur antiken und neueren Kunst. Ernst Homann-Wedeking gewidmet, pp. 49-52.

Richter 1968 = G. M. A. Richter, Korai. Archaic Greek Maidens.

Note

1 A. Furtwängler, “Von Delos”, AZ 1882, p. 322. See P. Kavvadias, Γλυπτά του Εθνικού Μουσείου. Κατάλογος περιγραφικός (1890-1892), p. 48.

2 J. Marcadé, “La pélerine de l’Artémis de Nikandré”, in J. Servais, T. Hackens, B. Servais-Soyez (eds), Stemmata. Mélanges de philologie, d’histoire et d’archéologie grecques offerts à Jules Labarbe (1987), pp. 369-375; Vorster 2002, p. 98. Donohue 2005, p. 203: decoration with colour alone.

3 Frequently, one of its sides, usually the right, remained open, with the leftover cloth creating thick folds which concealed the opening: Bieber 1967, pp. 27-31; M. Bieber, “Charakter und Unterschiede der griechischen und römischen Kleidung”, AA 88 (1973), pp. 430-431; A. Pekridou-Gorecki, Mode im antiken Griechenland. Textile, Fertigung und Kleidung (1989), pp. 77-82, 92, figs. 51-53.

4 Sometimes the peplos had a long and sometimes a short overfold (apoptygma), sometimes it was belted above the overfold (Attic style) and sometimes below (Argive style), while the so-called Laconian peplos was completely unbelted: Bieber 1967, pp. 33-34.

5 For a detailed description see G. Kokkorou-Alevras in G. Despinis, N. Kaltsas (eds), Κατάλογος Γλυπτών Εθνικού Αρχαιολογικού Μουσείου Ι.1. Γλυπτά των αρχαϊκών χρόνων από τον 7ο αιώνα ως το 480 π. Χ (2014), cat. 1.

6 Folds only just start to appear during the second quarter of the 6th century BC on both female and male garments, initially through the use of incisions and later through plastic rendering. For this reason and others it is very doubtful whether the statue of the new, unpublished kore of Thera (Karakasi 2001, pl. 76) should be dated to the Daedalic period, as might initially seem correct, since at the sides there are plastically rendered vertical folds that are reminiscent of folds on the garments of Samian korai of the second quarter of the 6th century BC. The earliest appearance of folds on the garments of korai is on two upper torsos from Chios (around 580 BC), where the folds are rendered with wavy incisions, while systems of parallel, carved folds similar to the folds of the new kore of Thera first appear on korai from the Heraion of Samos, such as on the lower torso of a kore statue (Mus. Vathi no. III P 78, c. 575 BC): Freyer-Schauenburg 1974, pp. 20-21, no. 5, pl. 3; Karakasi 2001, no. 5, p. 14, p. 153, table 4, pl. 3; Meyer, Brüggemann 2007, p. 80, no. 177). They are much more “calligraphic” on the korai of Cheramyes (570-560 BC): Richter 1968, p. 46, nos. 55 and 56, figs. 183-185 and 186-189; Freyer-Schauenburg 1974, pp. 21-27, no. 6, pll. 5-6; pp. 27-31, no. 7, pll. 7-8; Karakasi 2001, pp. 13-20, 24-28, 30-34, no. 6, no. 6A, pll. 4-9; Meyer, Brüggemann 2007, p. 78, no. 166, no. 167, p. 82, no. 194, while the lower part of a kore with similar folds from Didyma of Miletus is dated to c. 560 BC (Karakasi 2001, pp. 41, 60, 167 table, pl. 31, K 37a-37b; Meyer, Brüggemann 2007, p. 85, no. 216).

7 M. Bieber (n. 3, 1973), p. 431; A. Pekridou-Gorecki (n. 3), pp. 72-77.

8 It is not unlikely that the chiton was sewn out of a single piece of fabric: see n. 20 below. The peplos and chiton start to look similar in the second half of the 5th century BC; see Bieber 1967, p. 34.

9 See n. 12.

10 See Davaras 1972, pp. 26 -27, figs. 1-7, 9-10, 50-56; J. Floren, Die grieschische Plastik I (1987), pp. 124-128, pls. 6.3 and 7.1-2; J.-L. Martinez, La dame d’Auxerre (2000), p. 18, figs. 1-4; Kaminski 2002, pp. 85-86, 89-90, 92-93, figs. 160, 162, 167; Meyer, Brüggemann 2007, p. 74, no. 141.

11 For example, the terracotta statuettes: Richter 1968, pp. 33-34, nos. 23-27, figs. 86-102: second half of the 7th century BC. See also the ivory plaque EAM inv. no. 15 502 with Potnia Theron, “mistress of the animals”, from a Laconian workshop: Richter 1968, p. 36, no. 34, fig. 114. See also B. Schmaltz, “Peplos und Chiton – Frühe Griechische Tracht und ihre Darstellungskonventionen”, JdI 113 (1998), pp. 4-9, 10. Also, on the statue of the Lady of Auxerre the incised lines visible on her wrists, which have been interpreted as bracelets, possibly depict the ends of sleeves that would have been accentuated with bands of painted decoration: Richter 1968, figs. 78-79. See Donohue 2005, p. 139, fig. 19; p. 202. Opposed to this view is J.-L. Martinez (n. 10), p. 18.

12 B. Schmaltz (n. 11), p. 10.

13 Indeed, if we exclude the female figures of the Triad of Dreros (Richter 1968, p. 32, nos. 16-17, figs. 70-75. Kaminski 2002, pp. 83-84, figs. 157 a-e), where in fact the belt is not visible on the front but neither is the kolpos, on all other female Daedalic figures, it is very clear that the existence of a belt is emphasized on the front, and certainly the kolpos is completely missing. Even more recently, Donohue 2005, pp. 216-218, figs. 34-37, argues that the Lady of Auxerre wears two garments or, more correctly, “skirts”, one with folds on the inside and another heavy, rigid one, rather like the Greek and Balkan aprons worn as traditional clothing more recently. This view is comparable to that of V. Brinkmann of the garment of the “Peplophoros” on the Acropolis of Athens (an eastern type of garment: ependytes): V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (eds), Bunte Götter. Die Farbigkeit antiker Skulptur. Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek (2004), p. 56.

14 H. Kyrieleis, “Holzfunde aus Samos”, AM 95 (1980), pp. 97-98.

15 On the garment of perirranterion korai see M. Sturgeon, Isthmia IV. Sculpture I: 1952-1967 (1987), pp. 31-54, esp. 41-43. The lack of a cape (epiblema) on perirranterion korai is possibly due to the preservation of the traditional appearance of these korai: the long dress, however, of these korai also seems to be the sewn cylindrical chiton: G. Kokkorou-Alewras, “Caryatid Head in the Sparta Archaeological Museum and the Provenance of the Archaic Greek Perrirhanteria”, in Proceedings of the International Symposion “Νέα Ευρήματα Αρχαϊκής Πλαστικής από Ελληνικά Ιερά και Νεκροπόλεις” Athens 2-3 of November 2007 (2012), pp. 25-28.

16 Raubitschek 1975, p. 50; Donohue 2005, pp. 216-218, figs. 34-37. Similar vertical incisions on the hem appear on other representations of female Daedalic figures, which Donohue 2005, pp. 210-218, esp. 213-218, figs. 38-40, assembles, especially on ivory plaques from the sanctuary of Ortheia in Sparta, though not on all. On the steles from Prinias there are horizontal bands on the garments that seem to belong to an inner, narrower dress: Donohue 2005, fig. 41.

17 Above, n. 13.

18 For such fringes on Cretan garments see A. Lembessi, “Σχέσεις Σάμου και Κρήτης τον 7° αι.”, in N. C. Stambolidis (ed.), Φως Κυκλαδικόν. Μνήμη Νικολάου Ζαφειρόπουλου (1999), p. 150; the plates in A. Lembessi, Το Ιερό του Ερμή και της Αφροδίτης στη Σύμη Βιάννου Ι. Τα Χάλκινα Τορεύματα (1985), especially pl. 30 A 51, where the selvedge of the himation bears a meander band and fringes underneath, exactly in the same manner as the long skirts of the Cretan Daedalic korai. In my opinion, this proves that the dress of the Daedalic korai did not consist of three pieces of garment.

19 Sleeved chitons of statues of korai of the early 6th century, such as the kore in the Museum of Delos, no. 4062, from Aegina (Athens, Nat. Arch. Mus. inv. no. 73), Moschato (Athens, Nat. Arch. Mus. inv. no. 3859) and Paros (Paros Mus. inv. no. 802), have this central decorative band which continues to be found on the chitons of korai of the late Archaic period: Karakasi 2003, pll. 64, 79, 214, 234, 235-237, 248-260.

20 In fact, it is very likely that this central decorative band was woven into one end of the fabric of which the chiton was sewn, that is, it comprised the selvedge and thus it covered or concealed the existence of the vertical seam. It is, in other words, very likely that the seam of the chiton did not sit at one or both sides of the woman who wore it but rather was found at the centre of the front part. In this case, the central vertical decorative band would have arisen as a functional necessity.

21 Karakasi 2001, pll. 245, 238. Recently, V. Brinkmann, in V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13), pp. 53-58, drawing on the remarks of B. S. Ridgway, The Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture (1977), pp. 91-92, suggests that the overfold (apoptygma) of the “Peplophoros” is closed on the right arm and, based on his own observation that the decoration of her garment with a wide vertical band also continues on the upper torso but only beneath the overfold (apoptygma), argues that the “Peplophoros” is actually wearing an ependytes and a type of cape on her upper torso. Indeed, the continuation of the selvedge with its ornaments on the upper torso is the rule in similarly woven chitons (see n. 20 above). It is strange that this selvedge does not continue in the central part of the overfold (apoptygma), as we would expect if in fact the overfold (apoptygma) comprised a continuation of the fabric of which the peplos was made. However, as we know from the chitons and diagonal himatia of Archaic korai, the lower part of the chiton often had the same decoration as the diagonal Ionic himation, in contrast to the top part of the chiton, which was painted in one colour. Although there have been proposals for the existence of three pieces of clothing (J. Schäffer, “The Costume of the Korai: A Re-Interpretation”, Californian Studies in Classical Antiquity 8 [1975], pp. 241-250), ultimately the view has prevailed that the chiton was uniform from top to bottom and that the differing decoration of the two parts, as we described, is due to the artistic freedom of the Archaic painter rather than to a realistic element: Richter 1968, p. 8. See J. Boardman, Greek Sculpture. The Archaic Period (1978), p. 81.

22 See for example B. Schmaltz (n. 11), p. 5, figs. 1-2.

23 See Raubitschek 1975.

24 The collaboration of the conservator of the National Archaeological Museum, Ms D. Bika, and of the artist, Ms A. Drigkopoulou, was invaluable. I thank them both very much.

25 Unfortunately, in order for these methods to be used, full darkening of the area in which the statue is exhibited is necessary, which is not possible (at least for the time being) in the National Archaeological Museum, for security reasons. In fact, after getting permission from the director of the museum, Dr N. Kaltsas, and the curator of the Sculpture Collection, Dr E. Kourinou, whom I thank warmly, with the physicist Dr G. Antonopoulos (a specialist in optoelectronics) I attempted to use a fluorescent lamp (370 nm) at night, but the security lights that remained on did not permit an effective use of this method. I owe warm thanks to Dr Antonopoulos for his eager and selfless collaboration, as well as to the entire staff of the museum for their help.

26 Donohue 2005, pp. 216-218, fig. 42.

27 Maas 2002, pp. 65-67, fig. 136.

28 J. Boardman (n. 21), fig. 30; J. Floren (n. 10), pp. 125-126, pl. 7.1. Kaminski 2002, pp. 92-93, fig. 167.

29 See n. 11 above. For a drawing of the new kore of Eleutherna see J.-L. Martinez (n. 10), p. 44, fig. 43.

30 J. Boardman, J. Dorig, W. Fuchs, Die griechische Kunst (1966), fig. 142.

31 N. Kourou, “Τα Είδωλα της Σίφνου. Από την Μεγάλη Θεά στην Πότνια Θηρών και στην Αρτέμιδα”, in Πρακτικά του Α΄ Διεθνούς Σιφναϊκού Συμποσίου Α΄, Σίφνος 25-28 Ιουνίου 1998 (2000), p. 353, figs. 1-2. For the Naxian provenance see N. Weill, La plastique archaïque de Thasos. Figurines et statues de terre cuite I, ÉtThas XI (1985), p. 74 with n. 4, fig. 22 a-b; G. Kokkorou-Alewras, Archaische Naxische Plastik (Diss. Munich 1975), p. 88 K 3, 109, n. 6.

32 E. Walter-Karydi, “Bronzes pariens et imagerie cycladique du haut archaïsme”, in Y. Kourayos, Fr. Prost (eds), La sculpture des Cyclades à l’époque archaïque. Histoire des ateliers, rayonnement des styles, BCH Suppl. 48 (2008), pp. 29-30, fig. 20, where there are other examples of meander decorations on garments. See H. Kyrieleis, “Sphyrelata. Überlegungen zur früharchaischen Bronze-Großplastik in Olympia”, AM 123 (2008), pp. 177-198, esp. p. 187 with n. 32. See also fig. 1.

33 Raubitschek 1975; H. Kyrieleis, “Archaische Holzfunde aus Samos”, AM 95 (1980), pp. 97-98; A. Lembessi (n. 18), pp. 149-150.

34 J. Boardman, Excavations in Chios 1952-1955. Chios. Greek Emporio (1967), p. 63, pll. 88-90, especially pl. 88 no. 279, c. 660-630 BC and no. 317, c. 630-600 BC (similar meanders to that on the belt of the statue of Nikandre). For Ionian belts, their provenance and meaning, see G. Klebinder, in U. Muss (ed.), Der Kosmos von Artemis (2001), pp. 111-120. For Cretan belts of the 7th century BC and their origin, see Davaras 1972, pp. 27-29, 64-65; Raubitschek 1975, pp. 49-52. M. D’Acuntho, “L’Attributo della cintura e la questione degli inizi della scultura monumentale a Creta e a Naxos”, Ostraka 9 (2000), pp. 289-326. E. Walter-Karydi, “A Man, a God, a Hero: The Greek Kouros”, in G. Kokkorou-Alevras, K. Kopanias (eds), Methods of Approach and Research in Ancient Greek and Roman Sculpture (2007), p. 32; A. Hermary, “Kouroi à ceinture de la Crète aux Cyclades”, in Y. Kourayos, Fr. Prost (n. 32), pp. 183-192, pll. I-V, figs. 1-7, esp. 185-187. Although his assumption that only unmarried women wore these belts may be confirmed by the identification of the kore of Nikandre with the virgin goddess Artemis, the belts were nevertheless objects of everyday use, necessary to unmarried and married women alike, to hold the chiton at the waist. This does not exclude the possibility of the dedication of belts to goddesses before a wedding: J. Boardman (n. 34), p. 63.

35 Davaras 1972, pp. 18-19, figs. 23-24.

36 For the ways of fastening the belts on Cretan korai see Raubitschek 1975, pp. 49-52: figs. 4-5. See other ways of fastening bronze belts in J. Boardman (n. 34), p. 215, figs. 140-141; G. Klebinder (n. 34).

37 See Donohue 2005, p. 139, fig. 19, where the hem of the cape with the incised decoration is more visible. On this figure the incised scale pattern that decorates the chiton on the upper torso is also visible, being mainly conspicuous in the area of the breasts.

38 Davaras 1972, p. 26, fig. 38; Kaminski 2002, pp. 93-94, fig. 168.

39 E.g. figurine of a mourning woman from Boeotia: J.-L. Martinez (n. 10), fig. 25, but also on a marble statuette from Aegina (end of the 7th century: V. Brinkmann, Die Polychromie der archaischen und frühklassischen Skulptur [2003], p. 109, no. 1). For the basic colours of early Greek painting see I. Scheibler, “Die Vier Farben der griechischen Malerei”, AntK 17 (1974), 2, pp. 99-102; E. Walter-Karydi, “Prinzipien der archaischen Farbgebung”, in K. Braun, A. E. Furtwängler (eds), Studien zur klassischen Archäologie. Friedrich Hiller zu seinem 60. Geburtstag am 12. März 1986 (1986), pp. 23-41; V. Manzelli, La Policromia nella Statuaria Greca Archaica (1994), pp. 285, 287, 289-290, figs. 1-10. For the reasons behind the use of this trio of colours, see E. Walter-Karydi, “Χρως. Die Entstehung des griechischen Farbwortes”, Gymnasium 98 (1991), pp. 518-519. See V. Manzelli (this note), pp. 273-293, where the symbolic meaning of colours is perhaps overemphasized.

40 V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13), p. 33, pl. 33 (Berlin goddess); p. 182, fig. 326 (Phrasikleia).

41 See the Anavyssos kouros (N. Kaltsas, Το Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο [2007], pl. 240), Berlin goddess and “Peplophoros”, V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13), figs. 33 and 68. However, also see V. Manzelli (n. 39), pp. 280-281, who believes that the red of the iris visible today is due to the iron oxides contained in another colour.

42 For the light-coloured himation, see the Berlin goddess: V. Brinkmann, R. Wünsche (n. 13).

Indice delle illustrazioni

Il testo e gli altri elementi (illustrazioni, file importati) possono essere utilizzati con OpenEdition Books License, se non diversamente specificato.