Nation, Language, Islam

|Chapter 3. Creating Soviet People: The Meanings of Alphabets

Testo integrale

After an extraordinary concert the klezmer band Simkha gave at Kazan’s House of Actors, Nur apa, a Tatar-speaker, introduced me to the Yiddish-speaking leader of the mostly Jewish band. She presented him as Leonid Dawidovich, pronouncing the [v] in his patronymic like a [w], as the letter would be pronounced in Tatar. He responded, “I’m actually Leonid Davidovich—it was Russians who made it [w].” Nur apa nodded gravely with deep-seated recognition.

Field notes, Kazan, 25 April 2000

1Neither of the participants in this exchange spoke Russian as a native language. Yet, they both took for granted that formally introducing the band’s leader required following the Russian convention of addressing a person by first name and a patronymic constructed according to Russian morphology. Rather than question the appropriateness of using a Russian convention, the speakers focused on the pronunciation of a particular letter and treated that as the imposition of Russian cultural dominance.

- 1 See Jaffe (1996) and Schieffelin (1998) for similar analyses of the political implications of alph (...)

2This chapter begins to address the question of why people in the former Soviet Union think that language equals culture. It describes how Soviet nationalities policies made a direct link between languages, groups of people, and resource allocation based upon a cultural evolutionary model. It explores the relationships between the languages ethnic groups speak and the alphabets used for writing those languages. It demonstrates the ways intellectuals and politicians communicate ideas about cultural evolution obliquely using alphabets and how perilous these communications can be.1 Finally, it reveals that alphabets may be more dangerous today than they were during the Soviet Union’s formative period.

3In 1999, the Tatarstan government adopted a Latin-based alphabet for Tatar language, which had been written in Russian-based Cyrillic letters since 1938. Schoolchildren began learning the new alphabet in 2000. In 2002, the Russian Duma outlawed that alphabet as a threat to national security and mandated that all official languages of the Russian Federation be written in Cyrillic. That same year, Tatarstan stopped teaching schoolchildren the new Latin alphabet. Then, in 2004, the Tatarstan government took its case to Russia’s Constitutional Court, which threw the suit out. As of 2011, the status of Tatar’s Latin alphabet remains in flux. When I visited Kazan in 2006, someone gave me a Tatar book in the new alphabet and, when I asked whether printing the book wasn’t illegal, insisted that it was okay because private—not government—money funded its publication. Many Tatar online publications continue to use Latin instead of Cyrillic, but by doing so they are breaking the law and potentially putting themselves at risk of prosecution. The situation seems absurd. What does it matter to the Russian authorities what letters Tatars use to write their own language? A great deal, it turns out.

- 2 Advancing national minorities was part of a policy called nativization, which Martin (2001) calls (...)

4In order to understand why it matters to Tatars and Russians alike what alphabet Tatar is written in, it is necessary to know the trajectory of language development in the Soviet Union during the first decades of the country’s existence. While the Soviet central government engaged in great efforts to promote the country’s various languages in the 1920s as part of a campaign to support the advancement of hundreds of non-Russian minority groups, after the mid-1930s, the general trend shifted to one of persistently promoting Russian language above all others.2 Historically, this trajectory parallels one according to which Russian national culture became increasingly the standard against which non-Russian cultures’ evolutionary development was measured. That is, adopting Russian’s Cyrillic alphabet as a model for the alphabets of the Soviet Union’s other languages illustrates one way in which the Soviet state forced non-Russians to live with Russian linguistic and cultural hegemony.

5Since the 1920s, five different orthographic systems—some of which were modifications to already-existing alphabets—have represented Tatar language. The three significant changes were from Arabic script to a Latin alphabet in 1926, from Latin to Cyrillic in 1938, and the post-Soviet efforts to re-implement a “perfected” Latin script. Each change from one orthographic system to the next has been spurred by fundamental ideological transformations in the political order of the region. For Tatars and other non-Russians, attitudes about orthography have served as significant indicators of integration into and disaggregation from the Russian-run state, while Russians’ attitudes towards different alphabets indicate fluctuations in the strength of collective xenophobia.

6My discussion of Soviet language development is divided into two main parts. The first part provides a general background on Soviet language policies and traces the arc along which successive Soviet leaders raised the status of the majority language, Russian, vis-à-vis the other Soviet languages. The second part of my discussion illustrates how Soviet and post-Soviet nation-builders have used alphabet reform as a vehicle for political change and explains why alphabets continue to be volatile. It demonstrates how Soviets theorized that orthography would turn Russian imperial subjects into members of Soviet nationalities in the 1920s and 1930s and how, subsequent to the Soviet Union’s collapse, Tatar nation-builders have been attempting to employ alphabet reform as an instrument for decolonization.

7Post-Soviet debates about orthography make two things clear. The first is that when a group of people begins engaging in decolonization, the symbolic forms upon which that group draws to signify the new order are the very ones the colonial power has defined as essential aspects of its identity. The second point, further developed in subsequent chapters, is that while decolonization begins by rallying around certain essential identity traits, the process of decolonization changes the people involved in it with consequences they cannot predict. Thus, while post-Soviet Tatar intellectuals realized that they were pushing the envelope by reverting Tatar script to a Latinized version, they did not foresee that Russia’s central government would declare the new alphabet illegal.

Soviet Language Planning

- 3 After 1932 policies more frequently structured the practice of ethnography than the other way arou (...)

8In its initial stages in the 1920s, Soviet language planning efforts employed brigades of linguists and ethnographers to chart the nations and standardize the languages of the various peoples living in the USSR. These linguists and ethnographers organized their research findings, which were then integrated into Soviet nationalities policy, based upon a Leninist interpretation of Lewis Henry Morgan’s theories of cultural evo-lution.3 The more evolved a nationality was considered to be, the greater the number of resources and the larger the territory allocated to further its development. Resources went to create national schools, promote the creation of journals, newspapers, theaters, and operas in national languages, and to develop specific national costumes, dances and other artifacts of national culture. These efforts served to fix Soviet national cultures as distinct, bounded units.

- 4 Lenin (1914); Martin (2001).

- 5 Kirkwood (1989); Kreindler (1989); Lewis (1972). Beyond all of its inaccurate essentialist presump (...)

9Although most groups had never enjoyed the political autonomy that usually precedes a national movement, many were nonetheless dubbed “nations” or at least “nationalities.” The motivation behind this was to accelerate Soviet people along a cultural evolutionary trajectory by promoting their fluorescence and to give the illusion that they had the right to self-determination and were voluntarily opting to join the worldwide socialist revolution.4 One primary method for accelerating cultural development was to codify—and sometimes to create outright—standardized languages for newly discovered “nations.” Following the 19th-century European nationalist tradition, Soviet language codification practices presumed that each language was a discrete, self-contained system spoken by a single and likewise discrete nationality or nation. At the level of practice, this meant that individuals were supposed to speak their nation’s language as their “mother tongue” and that their children were required to study that language in government-run schools, whether or not the language was one that any of them spoke.5

- 6 Chikobaeva (1950: 15); Slezkine (1994b: 250–252). Marr’s method emerges from earlier theories of c (...)

- 7 See, for example, Austin (1992) on Karelian and Faller (2000) on Tatar.

10In 1926, two years after Lenin’s death, the All-Union Central Committee for the New Turkic Alphabet was formed. One of its most prominent members was Nikolai Marr, Director of the Soviet Union’s sole linguistics institute in the 1920s, and an advocate of Latin as the most socially evolved script. Marr’s linguistic, though not his orthographic, theories penetrated all levels of Soviet linguistics from the late 1920s through 1950. His main contribution to Soviet linguists was his Japhetic theory, which stated that languages constitute part of the Marxian superstructure and therefore change according to the economic base of the society in which they are spoken. Thus, Marr thought that each language emerged at a particular stage in history corresponding to a change in the mode of production through a process of hybridization with the previously existing language. Pitting himself against Indo-Europeanist scholars, Marr asserted that languages are not diversifying, but rather slowly fusing and that under communism all world languages will hybridize into a single language.6 Incorporated into Soviet nationalities policy to justify modifying the standards for non-Russian languages to make them more like Russian, the Japhetic theory promoted the shrinkage of many Soviet languages and the death of some.7

11Demonstrating how cultural evolution was translated into linguistic policy, N.F. Yakovlev, a proponent of latinization and a specialist in North Caucasian languages, published an article in 1926 called “The Problems of National Writing Systems for the Eastern Peoples of the USSR,” as a proposal for the First All-Soviet Turkologists Conference. It divides Soviet Eastern peoples into four categories, according to their perceived level of cultural evolution, and dictates which administrative resources should be devoted to their continued linguistic development. The article appeared in The Battle for a New Turkic Alphabet, a volume unavailable in the United States.

- 8 The chart is adapted from Yakovlev (1926: 36–37).

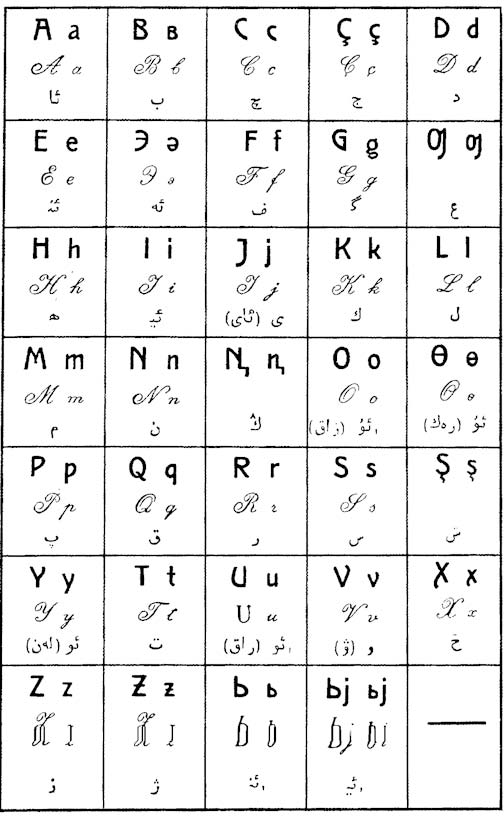

Figure 3.1. National Writing Systems8

- 9 Yakovlev’s presumption is contraindicated by the fact that at the turn of the 21st century when ha (...)

- 10 Morgan’s purported stages of development (savagery—barbarism—civilization) easily became conflated (...)

- 11 Schamiloglu (2001) views the Soviet Union as a continuation of the Russian Empire insofar as centr (...)

12Yakovlev’s proposal places speakers of various languages in a cultural evolutionary schema of nationalities according, in part, to their level of economic organization and literacy. Yakovlev incorrectly assumes that most people are monolingual and suggests that a language spoken by people who engage in agriculture cannot be used by a people who have their own proletariat, as if languages and means of production were intrinsically linked.9 Agriculture, of course, implies rural habitation, while the capitalism implicit in the existence of national proletariats, bourgeoisies, and intelligentsia connotes an urban setting. Yakovlev thus suggests that a residential locale’s size and permanence is a matter of cultural evolution.10 Imposing hierarchical distinctions based upon perceived and real linguistic and cultural differences among people—including means of production, development of a literary language, diversity in socioeconomic classes, and place of habitation—was the foundation of Soviet nationalities policies. As a consequence, nationality became a highly politicized category of identity at every level of society. Indeed, contemporary historian Uli Schamiloglu argues that judgments about stages of cultural evolution were politically motivated in ways that essentialized colonized peoples whom the authorities perceived as potentially threatening to Russian hegemony.11 The introduction of such hierarchical judgments paved the way for eventually lowering the status of certain nations.

Marrism and National Education

- 12 Published the following year under the title Marxism and Linguistics in the United States.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14 Stalin (1950a: 76).

13With the publication of Marxism and Problems of Linguistics in 1950, Stalin dethroned Marrist theoretical approaches to linguistics, asserting that languages were neither part of the base nor the superstructure and that, in fact, they were not class-based.12 That same year the newspaper Pravda published a discussion on linguistic problems, interspersed with Stalin’s corrections of the linguists’ “mistakes.”13 In these corrections Stalin dismisses Marr’s rejection of linguistic families (since Slavic languages are related); the class nature of language (since Russian did not significantly change after the October Revolution); and Marr’s famous four-element analysis (which claimed that original language consisted of four magical words).14

- 15 For example Chikobaeva (1950: 12) writes about Marrism thus, “Vocal speech, according to N. Ya. Ma (...)

- 16 For Stalin a language—as opposed to a class dialect—has its own basic lexical fund and grammar, an (...)

- 17 Stalin (1950a: 74).

- 18 Ibid., 71.

- 19 Stalin (1950c: 97; 1950a: 75).

- 20 Stalin (1950c: 98).

14Although Stalin’s linguistic revisions in the early 1950s characterized Marr’s ideas as inconceivably absurd, he had lent his official support to those very ideas for more than 20 years.15 And despite his rejection of Marrism, the ideas Stalin proposed beginning in 1950 still characterize the relationships between languages and their speakers unrealistically. For example, based upon nationalist ideas that emerged in 19th-century Europe, Stalin claims that single languages represent single bounded, monolingual peoples. That is to say, each identifiable “people” possesses a unique language.16 Though he dismisses the particulars of Marr’s stages of language development, Stalin nevertheless embraced both Marr’s presumption that languages develop teleologically and his theory of hybridization. He asserts that prior to the “slave-owning period of cultural evolution,” languages had sparse vocabularies and primitive grammars.17 But, Stalin maintains, progress has been made. For example, since the period when Pushkin lived in the early 19th century, Russian grammar has improved and many obsolete words have disappeared.18 Stalin explains that hybridization occurs when “one of the languages emerges triumphant and the other dies,” during which “the vocabulary of the victorious language is somewhat enriched at the expense of the defeated language,” and which “is what happened, for example, with Russian.”19 After the worldwide victory of socialism, “national equality will be a reality” and “zonal” languages—which may be German, English, and Russian—will “coalesce into one general international language.”20 Stalin thus implies that Russian will be “victorious” above all other Soviet languages, including his native Georgian.

- 21 Kreindler (1989: 53, 56).

- 22 See Artiunov (1978), for an example of the former and Grant (1983) and Lewis (1972) as examples of (...)

15It was not until Khrushchev came to power that Stalin’s russocentrism was adopted as official policy applied to the national education of the USSR’s minority peoples. Under Brezhnev russocentrism in the Soviet Union achieved grotesque proportions, as Russian language became endowed with high morality. Non-Russians were encouraged to abandon their native languages because doing so was touted as progressive, mature, and “according to the laws of natural development.”21 At the same time, Soviet ethnographers began to laud bilingualism, praise of which filtered into work by western scholars on ethnic minorities and schooling in the USSR.22

- 23 Kreindler (1989).

- 24 Maksimov (1990: 64).

- 25 Maksimov’s implies that Tatar semantic fields have become less narrow due to Russian influence, fo (...)

- 26 For example, Maksimov wants to introduce the Russian word politik to replace the already existing (...)

16When Gorbachev came to power in 1985, he did not significantly alter Soviet language policies. However, like Khrushchev, Gorbachev did not actively seek to glorify Russian.23 Even so, some Soviet scholars continued Russian’s glorification without direct government prompting. The debates published in Kazan in a volume called Bilingualism: Typology and Function, edited by Tatar linguists Zakiev, Ganiev, and Iskhakova— all prominent nation-builders—in 1990, illustrate the continuation of Russian linguistic hegemony into the glasnost period. In this volume a linguist with the Russian surname of Maksimov lauds the “evolution” of the “old, artificial Tatar literary language” through what he calls the “broadening of Tatar semantic fields.”24 Despite Maksimov’s denial that Russian has influenced Tatar, his “evolution” in fact constitutes lexical and morphological russification of the language.25 Maksimov calques Russian linguistic features into Tatar, impoverishing the literary language by erasing certain aspects of Tatar grammar and the history of linguistic exchange between Tatars and the Ottoman Empire. This, moreover, decreases the sheer number of words in the USSR’s collective linguistic repertoire by replacing existing terminology in non-Russian languages with Russian words.26

- 27 Sagdeeva (1990: 127).

- 28 Sagdeeva objects to the following sentence on the grounds that it suffers from “interference” from (...)

- 29 See my article, Faller (2000), for a more detailed description of prescriptive grammars in the ear (...)

17Arguing the other side of the debate is a linguist with the Tatar surname, Sagdeeva, who contends that Soviet politics narrowed the social functions of Tatar and blames Stalin for this because he “deviated from Leninist norms.”27 Sagdeeva complains of Russian interference in urban Tatar speech with examples that closely resemble Maksimov’s calques. Thus, she objects to the word kul’turaly—an adverb formed from the Russian noun kul’tura– meaning “in a cultured way.”28 But, the Tatar word for “cultured” [mädäni], which is borrowed from Arabic, references a more elevated social world than the one indicated by the quotidian “kul’turaly.” Not dissimilar from Maksimov’s “evolution,” replacing kul’turaly with mädäni would narrow Tatar’s functional range and deny the language’s lexical diversification during the Soviet period.29

18The approaches of both these linguists rely upon data that skew observations of speech practices in order to make political claims. Political claims likewise define the terms of Soviet and post-Soviet orthographic debates. The terms of these debates, which continue to be deeply grounded in assumptions that emerge from the particulars of Soviet history, disclose ideological controversies over the relationships between languages, nations, and levels of cultural evolution.

The Politics of Graphics

- 30 Lenin (1970). This shift was likewise supported by most Turkic intellectuals in the service of the (...)

19Taking a stand against Russian imperialism, Vladimir Lenin sought to develop the ethnic cultures of groups living within Soviet territory. As part of this, Lenin rejected the idea that Russian language should have a privileged role in the new Soviet state. Since Russian is written in Cyrillic, Lenin supported Soviet planning to create non-Cyrillic alphabets for previously unwritten languages and to latinize Turkic and other languages.30

- 31 Turkic-speakers who did not convert to Islam, for example, Tuvans and Yakuts, never adopted an Ara (...)

20Up until the 1920s, Soviet Muslims who spoke Turkic languages— including people from present-day Azerbaijan, Bashkortostan, Crimea, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and republics in the North Caucasus—wrote in various Arabic scripts which they considered to represent a common Turkic tongue.31 This all changed during the USSR’s state-building period. At that time, Soviet authorities sought to parse Muslims into separate nations. Because they considered the primary indicator of a nation’s existence evidence of a national language, where a definitive language didn’t already exist, they were ready to urge on its creation.

- 32 In anthropology, the study of societies emerged historically in England, while the study of cultur (...)

21In the past century, two different ideologies have propelled changes in how the Tatar language is written. First, during Soviet state-building in the 1920s, an anti-colonialist ideology prevailed according to which each identifiable nation had the right to its own non-Russian alphabet. Nested within this ideology was a belief that an alphabet is supposed to both represent a language’s phonology transparently and reflect the culture associated with that language. Second, in the late 1920s and 1930s another ideology emerged, one which maintained that changing non-Russian languages to make them more closely resemble Russian could accelerate a nation’s cultural evolution.32

- 33 No scholar thus far has analyzed Soviet orthographic reforms to present the big picture of alphabe (...)

22Changes in Soviet orthographic policies altered people’s lives and differentiated Turkic-speaking Soviet Muslims in at least two ways. First, generational splits occurred twice in the 20th century when new alphabets rendered previously existing reading publics suddenly illiterate. This unusual form of illiteracy had two major social effects, excluding formerly literate people from certain kinds of social and political participation and preventing people literate in current orthographic systems from familiarizing themselves with works published in previously used alphabets. Second and quite profoundly, orthographic changes have promoted the differentiation of Turkic-speakers into separate nationalities. Prior to the alphabet changes of the early Soviet period, people who were literate in one Turkic language variety could read texts written in any other variety. At the time vowel differences constituted the greatest barrier to communication among speakers of different Turkic language varieties and Arabic scripts did not mark them. The creation of different alphabets has fragmented knowledge once generally accessible to Turkic-speakers. In the post-Soviet period, this fragmentation causes minority nationality scholars to think that their particular national language was singled out for russification, since they are unable to read source materials in other languages which prevents them from piecing together the big picture of Soviet alphabet reform and its effects.33 This is part of the legacy of Soviet colonialism.

23L.I. Zhirkov, a specialist on Tajik language who was employed by the Soviet government to modernize non-Russian languages, clarifies early Soviet period views about the presumption of a one-to-one correlation between nations, languages, and alphabets, as follows:

- 34 Zhirkov (1926: 20).

You only have to open up a map of our Soviet Union and you will see, by the geographic nomenclature itself, that on the territory of pre-revolutionary Russia tens of new national republics and provinces are now located. Under each new geographic name is hidden a new, young, national culture—at the very least, under the majority of them. A national culture, naturally, presumes national schools. Schools require books, print, and an alphabet. A young national culture demands that this book, this print, this alphabet should not be ethnic Russian, but rather one’s own.34

- 35 Pavlovich (1926).

24Not only did Soviet linguists in the 1920s posit that young national cultures deserved their own alphabets, but, as the famous Orientalist M. Pavlovich suggested, those alphabets should be simple and easy to acquire.35

- 36 This orthographic ideology also governed the adoption of a Latin script in the Republic of Turkey (...)

- 37 Zhirkov (1926: 21). Heartfelt thanks to my dear friend Maksim Kolopotin for his most insightful ex (...)

25Beyond this, Soviet linguists—especially Zhirkov—tended to equate orthographic systems with political ones.36 Zhirkov explicitly articulated a conviction that Cyrillic orthography generated the corrupt politics and inequality associated with Byzantium, while Latin scripts promoted incorporation into Enlightenment-influenced, western political structures that guaranteed equality to everyone. Thus, he declared that Russian politics had been necessarily Byzantine—that is, corrupt, patriarchal, and rife with intrigues, cruelty, cunning, and protectionism—because the Russian alphabet is based on Greek, while speakers of western Slavic languages (specifically, Poles and Czechs) had been incorporated into western political structures where a Latin alphabet reigned.37 According to this belief, adopting the Latin alphabet was essential to implementing the new, modernist Soviet order.

The Orthography Merry-Go-Round

- 38 Kurbatov (1999).

- 39 Evidence of dissent comes from one contributor to the government-sanctioned volume, The Battle for (...)

- 40 Lenin (1970).

- 41 Pavlovich (1926).

- 42 Zhirkov (1926).

- 43 Agamaly-Ogly (1926: 14); Ibrahimov in Kurbatov (1999).

26Although some Muslim intellectuals in the Russian Empire had begun to advocate for a Latin alphabet as early as the mid-19th century, it was not until 1920 that the Russian authorities began to take their requests seriously.38 While the majority of Soviet linguists supported the adoption of Latin, in contradistinction to the later situation under full-blown Stalinism, dissent was allowed.39 Advocates of latinization, like Lenin, considered it to be technically easier to learn than Arabic, and saw its adoption as a means to promote mass literacy.40 Pavlovich claimed that children could learn to read in Latin script in a month or less, asserting that mastering Arabic script required a year of constant study.41 Zhirkov thought Arabic inappropriate because it contained too few letters to represent all the sounds of “Eastern” languages.42 Samad Agamalioglu, one of Azerbaijan’s foremost cultural leaders, and Galimjan Ibrahimov, a leading Tatar linguist, proposed that Arabic was defective for teaching school subjects, since one reads mathematical formulas from left to right, while Arabic is read from right to left.43

- 44 Broydo (1926); Crisp (1989).

27At least as important a reason, and perhaps the primary one, for wanting to create a Latin alphabet was Arabic script’s perceived unsuitability due to its associations with Islam.44 Like things Byzantine, Islam was considered to be antithetical to openness and equality. Thus, statements supporting latinization contained the clear message that Turkic languages should discard their Arabic scripts in order to shed their Islamic components.

- 45 During the following school year, 1927–28, a latinized Tatar began to be taught in technical and s (...)

- 46 Kurbatov (1999).

28In 1926, Tatar’s first Latin alphabet was introduced. Almost immediately, government linguists decided that it differed too much from the Latin alphabet that had been introduced for the Azeri language in 1923. In March 1927, the Yangalif (“New Alphabet”) Society held a conference in Kazan during which the participants presented their cases for the need “to perfect” Tatar’s alphabet and made a case for creating a common Latin alphabet.45 Subsequently, the All-Union Central Committee of the New Turkish Alphabet (VSTsKNTA) unified the country’s Turkic alphabets into a single Latin orthographic system.46 Although latinization rendered a generation of readers illiterate, the unified alphabet did not hinder communication across geographical regions. It represented the same sounds with the same characters in all the Soviet Union’s Turkic languages, with only the slightest modifications made in local regional publications.

- 47 See Smith (1993) for more on the split between linguists who supported the phonetic over the phono (...)

- 48 Slezkine (1994a).

29However, a dispute soon broke out among several key Soviet linguists, including Zhirkov and Baudouin de Courtenay’s student Yevgenii Polivanov, over what the relationship should be between written language and speech.47 Several linguists thought that written language should mimic speech as closely as possible, while others opined that phonetic differences were not important as long as speakers didn’t perceive them as meaningful. (That is, the differences weren’t phonological.) The sides taken in this dispute reveal two characteristics of the development of Soviet nationalities. First, they foreshadow what Russian historian Yuri Slezkine aptly calls ethnic particularism—the division of people living in the former Soviet Union into ranked groups each seeking to promote the interests of their own nationality—which has made creating a common Latin alphabet in the post-Soviet period an untenable goal.48 Second, they reveal a trend towards promoting Russian over other Soviet languages. Though Soviet linguists in the late 1920s–early 1930s created different orthographic systems for closely related Turkic languages, they quickly began to model their alphabets after features found in Russian. In order to understand the particularities of these models, it is necessary to have some familiarity with three traits common to Turkic languages—namely, phonemic patterning, vowel harmony, and agglutination.

- 49 My observation is that the [ž] allophone sometimes, but not necessarily, indicates a more emphatic (...)

30First, Turkic languages possess [y]/[ž] sound alternation as part of their phonemic patterning. For example, the word for “no” can be either yok or žok, depending upon the dialect. Anatolian Turks say yok, while contemporary Kazakhs say žok. The Tatar literary word for “no” is yuk, but a single speaker may say yuk, yok, žok, or žuk over the course of a few sentences depending upon what feels good to say at a given moment, according to Fäüzia, a village-born, middle-aged schoolteacher.49

- 50 In other words, it possesses phonemic significance.

- 51 Schafer (1995).

31However, when educated Tatars hear Bashkirs (a nationality whose titular republic lies just east of Tatarstan and whose cultural evolutionary ranking is lower than Tatars’) say yuk/yok or žuk/žok, the choice of [y] or [ž] has significance.50 From a Tatar-speaking perspective, a Bashkir saying yuk/yok is speaking Tatar, while if he or she says žuk/žok, the language is Bashkir. For example, when I visited Bashkortostan in June 2000, my Tatar friends—including Fäüzia—decided I should be interviewed on Bashkir radio. They took me to a radio station and introduced me to a Bashkir journalist who was eager to interview me. We went into the sound studio. As soon as the tape started rolling, the journalist, who up till then had been speaking something indistinguishable from Tatar as I knew it, altered her speech to say, inter alia, žok instead of yok. Afterwards, when Fäüzia recounted the story of this encounter to her mother Nur apa, she stressed that the journalist switched from Tatar to Bashkir. However, when I asked Fäüzia what language Nur apa (who was one of Kazan’s few Tatar language teachers during late socialism) was speaking when she says žok or žuk, Fäüzia asserted that the language is Tatar. Hearing [y]/[ž] variation as meaningful or not emerges from Soviet language codification processes in the 1920s-1930s.51

- 52 For more on the concept of verbal hygiene, see Cameron’s (1995) book by that name.

32Thus, the dispute that began in 1927 concerned whether written forms should mimic spoken language or whether they should promote verbal hygiene by imposing standard literary forms—like [y] in place of [ž]. Verbal hygiene prevailed and Soviet linguists created a third Latin orthographic system for Tatar, which the All-Union Central Committee of the New Turkish Alphabet accepted at their 1929 Congress.52

33A second feature of Turkic languages common to all standardized versions, except Uzbek, is vowel harmony. Vowel harmony requires that all the vowels in any indigenous word are spoken completely in the back or completely in the front of the mouth. So, for example, yuk is back, while mächit—the word for “mosque”—is front. Vowel harmony becomes more apparent in longer words, often created through a third Turkic linguistic feature—agglutination. Agglutination requires that words that might be represented by phrases in English are built from roots using affixes. For example, yuk means “no”; yuklik means “absence”; and yukliktan would mean “due to the absence” of something. Similarly, while mäachit means “mosque”; mächitim means “my mosque”; and mächitimdä means “in my mosque.” In all their forms these words adhere to vowel harmony and are thus pronounced either completely in the back or the front of one’s mouth.

- 53 Native speakers do adhere to front-back oppositions in speech, even though their metalinguistic te (...)

34Unlike the rules that govern Turkic vowel harmony, Russian vowels are either hard or soft. Also dissimilar from Turkic languages, Russian’s softness/hardness is not patterned onto entire words. Rather, it occurs idiosyncratically and requires memorization. When Tatar began to be written in Russian script, front vowels were represented as if they were soft (for example, a replaced a), and back vowels as if they were hard. As a result, when present-day Tatar teachers explain Tatar vowel harmony, they speak of it as the Russian distinction between softness and hard-ness.53

35At the 1929 Congress, linguists S. Atnagulov and M. Fazlullin—both ethnic Tatars—announced, “The law of vowel harmony, a quality of the Tatar language, is a reactionary law and a conservative tendency.” Shortly thereafter, they declared that written Tatar would no longer mark vowel harmony. In a remark espousing Marr’s theory of language hybridization, Fazlullin gave the reason for taking this measure as follows:

- 54 Kurbatov (1999: 97).

In the future, languages will unite, that is, in N. Ia. Marr’s words, languages of different systems will take each other’s elements into themselves using the “crossing” path. As a result, whichever it turns out to be, only one language will remain in the world.54

- 55 Alpatov (1991).

36Marr proposed that agglutinative languages were at the clan stage, while inflected languages exist in class-based societies. Fazlullin’s statement demonstrates a new application of Marr’s ideas. Instead of allowing languages to develop through their purported evolutionary stages, they receive a push in the right direction.55 Decreeing that the Tatar language be denuded of one of its fundamental features was supposed to accelerate its speakers along an imagined evolutionary trajectory into a class-based society.

- 56 Research by American sociolinguist William Labov (1966) on how lower middle class people try to ad (...)

- 57 Other research on Soviet minority languages demonstrates that this was the general attitude during (...)

- 58 I would argue, contrary to the generally received interpretations of Marr’s ideas, that there were (...)

37Different from how linguists usually conceive of languages, Fazlullin’s theory does not include speakers and his fusing apparently proceeds without their interference.56 Indeed, Soviet linguists treated languages as autonomous vehicles for progressive change and social engineering.57 While this perception became deeply entrenched in the 1930s, Tatar-language archival materials demonstrate that it took hold as early as the late 1920s.58

- 59 For example, kübäräk which means “more,” came to be spelled kübräk.

- 60 Kärimullin (1997). Iskhakov (2005: 81–84) sees this as a continuation of a process begun in the 19 (...)

38In 1933, Tatar’s Latin alphabet was modified once again. The spellings of some words were changed so that they no longer followed the Turkic pattern of alternating consonant-vowel-consonant.59 Instead of using writing to record speech, Tatar spelling began to imitate Russian orthographic conventions. Additionally, new spelling rules were introduced for words borrowed from Arabic and Farsi that marked them as foreign.60 Marking loan words from “Muslim” languages as foreign implies that Islam is alien to Tatar culture and was clearly devised to bolster contemporaneous Soviet antireligious campaigns. Paradoxically, since the Soviet Union’s collapse, Tatars often enunciate Arabic loanwords using hyper corrected pronunciation so that the words sound, in effect, more Arabic than Arabic. They consider this a way to get back to authentic Tatarness.

- 61 These revolutionary tendencies included not only anti-imperialist improvements in the lives of sub (...)

- 62 Armenian, Georgian, the three Baltic languages (Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian), Yiddish, and A (...)

39In 1937, the last change was made to Tatar’s Latin alphabet. The letter [w] was added. The following year, without any discussion or debate, Stalin decreed that Tatar language should be written in Cyrillic. Historically, this decree coincided with the death of Soviet society’s revolutionary tendencies.61 By 1941, 60 of the Soviet Union’s 67 written languages had been cyrillicized.62

- 63 Attempts were likewise made to change other Soviet languages so that they more closely resembled R (...)

40In 1938 Fazlullin asserted that the goal of adopting Russian’s alphabet was to change Tatar from an agglutinative to an inflected language like Russian.63 He made quite clear that this signified a leap forward in cultural evolution:

- 64 Fazlullin [1938] in Kurbatov (1999: 110).

As a result of taking the Russian alphabet in its entirety...the possibility of inserting the written system of an inflected language in some places is born for us, and it is necessary to insert it...The idea is that Tatar language is beginning to enter the inflected system from an agglutinative system. It should be required to make changes in the areas of orthography, phonetics, and morphology. This will clearly be a progressive step.64

41Xälif Kurbatov, a present-day Tatar historian and author of an extremely informative book on the history of Tatar orthography, comments with regards to Fazlullin’s assertion, “having understood these words, [one sees] the alphabet project was not about Tatar language at all.” He continues:

- 65 Kurbatov (1999: 110–111).

Indeed...the [project’s] creators held in their eye more the goal to change the native language into another language, to make the native language fit into the template of another language. They wished to change the Tatar language from an agglutinative language into an inflected language, that is, they relied upon N. Ia. Marr’s theory according to which languages pass through stadial steps of growth.65

- 66 This perspective is soundly supported by Geraci (2001).

42Kurbatov concludes that cyrillicizing Tatar was simply a continuation of pre-revolutionary Russian missionary activities in the Middle Volga region, the intention of which, he asserts, was to russify the population.66

- 67 Tatar’s original Cyrillic alphabet did not mark sounds particular to Tatar otherwise, for example (...)

- 68 Kurbatov (1999: 109).

- 69 Kärimullin (1997: 17).

43Although six letters were added after 1939, Tatar’s first Cyrillic alphabet did not contain any additional graphemes to mark Tatar sounds not found in Russian.67 Fazlullin explained that this was because adding extra letters would require the production of special typewriters and cash registers. He asserted that if allowances were made for Tatar’s phonology, the same words written in Russian and Tatar would be spelled differently.68 Fazlullin argued that Tatars would make fewer mistakes writing Russian, if an unmodified Cyrillic alphabet were to represent the Tatar language.69 Making faultless Russian the central concern in the question of how to write Tatar demonstrates a fundamental attitude shift. That is, by the late 1930s, the Soviet government’s position was that knowledge of Tatar held value only insofar as it facilitated Russian’s dominance.

- 70 Yakovlev (1926: 36–37).

44In 1926, Yakovlev had declared that the languages of nationalities of the least developed type should “completely conform to the alphabet of the dominant nationality” to ease “transition to the language of the dominant nationality.”70 Applying his declaration to the situation in the 1930s signifies that writing Tatar in the Russian alphabet lowers the Tatar nation’s status in Soviet hierarchical structures, and indeed, excludes all nationalities but Ukrainians, who were already writing in Cyrillic, from the category of economically and culturally dominant nations. It suggests that Tatars, along with other minorities previously granted their own alphabets, were expected to make the transition to Russian language.

45Thus, a revolutionary program to develop the literary languages of the various ethnic groups living on Soviet territory was transformed into a policy for accelerating the cultural evolution of those ethnic groups. Language was equated with culture and Russian language and culture became increasingly represented as the most progressive and civilized, and, as such, the endpoint towards which non-Russian languages and their speakers should seek to evolve.

- 71 See Faller (2000) for more on Soviet intellectuals’attitudes towards the syntactic and morphologic (...)

- 72 This difficulty is compounded by lexical differentiation between Turkic languages, also a product (...)

46Although one of the long-term consequences of introducing Cyrillic alphabets, as well as Russian phonology, morphology, and syntax for Turkic languages, was to russify Turkic-speakers linguistically, these policies had another, equally important social effect.71 They divided speakers of closely related Turkic dialects orthographically. After 1938, the Soviet state used different Cyrillic alphabets, the letters of which appeared in dictionaries each in a unique alphabetical order, for Turkic language varieties spoken in Tatarstan, Bashkortostan. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and so on. Indeed, the Cyrillic alphabets in use from 1939 until the Soviet Union’s collapse provided different spellings—not only for vowels, but also consonants—for words common to all of them. While representing vowels differently in related dialects may render it somewhat difficult for speakers of one dialect to read another dialect, changing the orthographic representation of consonants indisputably increases that difficulty.72

- 73 Stalin (1950a, 1950b); Schafer (1995). As is clear from the implicit argument presented by Maksimo (...)

47The alphabet changes of the early Soviet period caused broad social change in three concrete ways. First, they were an important step in the creation of “unique languages,” which Stalin considered one of the criteria for nationhood. Second, they discouraged pan-Turkic connections across newly created borders.73 Indeed, while some ex-Soviet Turkic-speakers communicate orally with members of other Soviet Turkic nationalities in the post-Soviet period, I have never met one who reads literature in another nationality’s language. And third, they denied members of minority nationalities access to their own written history, since they couldn’t read texts published in previously extant writing systems.

The Outlaw Alphabet

48After 1939, these once hotly contested questions concerning orthography lay dormant until Gorbachev accelerated his policy of glasnost in the late 1980s. Since the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, however, one of the core independence projects in the various Turkic republics—including Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tatarstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan—has been the re-introduction of Yangalif (also called latinitsa). To this end, two international congresses were convened, the first in Ankara in 1990 and the second in Kazan in 1994. The goal of these meetings was to create a common Turkic alphabet so that Turkic-speakers of different nationalities would be able to read each other’s publications. The model that representatives from the Soviet Union took home from the congress in Ankara closely resembled the alphabet used for Anatolian Turkish. However, once the Soviet linguists returned to their respective republics, they each modified the common alphabet to accommodate sounds unique to their own native language. The desire to maintain sound particularities in writing suggests that the linguists consider orthographic particularism to represent ethnic difference. The existence of a tension between this desire and the contrary tendency to embrace pan-Turkic linguistic commonalities makes it evident that Soviet language policies effected a real transformation with regards to creating national divisions among the USSR’s Turkic-speakers.

- 74 By and large, all but the most privileged former Soviets, who have access to better quality teachi (...)

49Besides the value of being able to communicate in written form with speakers of similar dialects without having to revert to Russian, Tatar-speakers cite other benefits to adopting a Latin script. These include greater access to globalized computer technologies and improved spoken ability by children studying Tatar, who, they believe, will no longer pronounce Tatar texts as if they were reading Russian. My research reveals that pronouncing Tatar as if it were Russian is indeed widespread among urban school children. Representing Tatar in an alphabet other than Cyrillic may encourage children to read texts according to a phonological system that is not based on Russian. However, results would still depend on the quality of education.74

- 75 I transliterate front [a] as a.

50Moreover, the new latinized version of Tatar contains three specialized graphemes—for example, [ə] for front [a]—which do not appear on a standard Latin keyboard.75 This suggests that the reasons for adopting latinitsa are grounded as much in the ideological as in the quotidian.

51In February 2000, I attended the final day of a three-day conference on Tatar-language education at one of Kazan’s leading cultural institutes. The entire conference was conducted in the Tatar language and I recognized both at the podium and in the audience many people I knew as key Tatar nation-builders. They were university professors, textbook writers, school administrators, and teachers. I was the only non-Tatar there. The conference took place within a Tatar discursive world impermeable to Russian monolinguals.

- 76 See Yurchak (1997). Like many statements scholars make about the Russia of Moscow or St. Petersbur (...)

52The air in the auditorium where we all sat in attendance was warm and close. As I listened to one lecture after another, I noticed that many of my fellow attendees took turns dozing off. Others passed notes to each other. The scene reminded me of Yurchak’s description of Communist Party meetings in the late Soviet period, where Komsomol leaders would express their ideological apathy by engaging in other activities, such as reading books held in their laps out of view of the speakers.76 But, these people weren’t apathetic—they may have been bored, but the ones I knew personally worked doggedly to improve the standards of Tatar education.

- 77 I am translating the word törki as Turkish.

- 78 In contemporary Russia “standart” is usually used to mean economic standard or standard of living, (...)

53During the course of the afternoon, two prominent Tatar nation-builders expounded profoundly ideological reasons for wanting to switch to Latin script. The first of these, a history professor at Kazan State University, proclaimed from the stage that Russians had no ideology and no concept of democracy. He asserted that to attain an “American-European” standard, Tatar language needed a Latin script, for, he claimed, “Russian-Slavic” sorts of ideas are expressed in Cyrillic. The professor then spoke of a single Turkish people, saying that, although pan-Germanism and pan-Slavism are acceptable propositions, pan-Turkism is considered inherently bad.77 “Since,” he continued, “there is a Turkish people, there must also be a Turkish standard, which, unlike Cyrillic, would be the people’s standard.”78 A second nation-builder, the linguist involved in creating the Tatar-Russian dictionary currently in use, asserted that the policy of writing Tatar in a Cyrillic alphabet had been part of an effort to absorb Tatars into the Russian nation. He perceived Cyrillic’s introduction as part of a plan to destroy a people by turning two nations into one. Both nation-builders reiterated the mid-1920s ideology according to which alphabets are supposed to indicate entire systems of cultural organization. However, each did so in a different way. The professor argued for distancing Tatars from Russian-Slavic culture by switching to an orthographic system he equated with America, Europe, and all Turks. The linguist, by contrast, contended that Latin script is required to prevent the continuation of Tatar cultural genocide, as Tatar-speakers often call it.

54The Tatar linguists who favored adopting latinitsa held different opinions about what letters that alphabet should contain. I interviewed one of them, a well-known senior linguist, in December 2000. During the interview, which only concerned linguistic matters, he became very nervous, indicating at one point that someone was eavesdropping at the door to his office. We opened it to find one of his graduate students standing there. The linguist explained to me that there had been a major rift among the members of The Committee to Re-introduce Latinitsa and it had split into two factions. One faction, which the aforementioned Kurbatov supported, wished to reintroduce the 1920s Yangalif alphabet. The other faction—his own—wished to update or “perfect” Yangalif, in part by introducing Turkish letters to represent sounds that had been denoted by Russian soft signs in the 1920s Latin script. By way of criticism of the former position, the linguist pointed out that soft signs cannot be represented on a Latin computer keyboard (which likewise holds true for the three special letters he advocated including). The linguist added that proponents of perfecting Yangalif had been accused of being Turkish spies. Despite these accusations, the script eventually adopted was Perfected Yangalif. It contains Turkish letters and an altogether new letter, while retaining two modified Cyrillic graphemes.

55Following Crimean Tatars in Ukraine, and the Republics of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, in September 1999 Tatarstan’s President Mintimir Shaimiev finally signed into law the long-debated Latin alphabet for the Tatar language. Adopting Perfected Yangalif immediately sparked a vociferous negative reaction from Moscow, most apparent in disparaging press coverage of Tatarstan’s latinization project.

56A September 1999 article published in the Moscow newspaper Izvestiya provides a quintessential example of Russian media coverage of the issue. The article’s title—“Iazychniki: ‘Iazykovaia reforma’ zadumannaia vlastiami Kazani, mozhet possorit’ russkikh i tatar—is a play on words. Literally translated, it means “Heathens: The ‘language reform’ thought up by the authorities in Kazan may make Russians and Tatars quarrel.” Used as a pun here on the Russian word for language—iazyk, “iazychnik” means both “heathen” and “language person,” thus implying that people who focus on language questions are barbaric. The article’s byline lists Gayaz Alimov, a staff journalist who regularly reports on foreign affairs (and whose Arabic-derived Tatar name means “Lucid Scholar”), and Maksim Iusin, Izvestiya’s Editor of International Affairs. Its co-authoring by an apparent Tatar and an apparent Russian both symbolizes ethnic solidarity and implies that negative reactions to latinization are not the product of Russian nationalism.

57Even so, the genre of argument Alimov and Iusin adopt is not uncommon among Russian nationalists. Inverting the central ideology from the USSR’s 1920s state-formation period, which asserts that every nation has a unique language, they claim that a group not in complete possession of a national language cannot be considered a nation. Moreover, they imply, if people do not think in their national language and speak it fluently, then any claims they make on the basis of nationhood are inauthentic machinations intended to manipulate politics and power hierarchies to their advantage. This attitude is part of the fabric of everyday life, as when Russians living in Kazan would confide to me that Tatars do not speak or think in Tatar. At such moments, they either pointedly implied or stated outright that language promotion is pure nationalism and nothing more than an attempt to supplant Russians from their rightful positions of power.

- 79 My research on code-switching among bilingual Tatar-Russian speakers demonstrates that some speake (...)

58Alimov and Iusin’s mocking derision of Tatarstan’s latinization campaign demonstrates how debates about alphabet reform frequently centralize minutiae marginal to the problems associated with reform, which approach makes alphabet reform appear a petty endeavor. Thus, Alimov and Iusin claim that there are Tatars who have adopted the Russian word for yes [da] in place of the Tatar “aie” and assert that writing “da” in Latin letters would be absurd. The absurdity of writing da in Latin is treated as if it were self-evident, unsupported by linguistic or other evidence. More to the point, their claim is unfounded.79 Nevertheless, Alimov and Iusin’s article takes as its premise the notion that Tatar language is so corrupted, and ethnic Tatars are so linguistically russified, that they have given up core words, such as that for “yes.” Consequently, their train of logic implies, no authentic Tatar language spoken by authentic Tatars exists. Rather, people seeking language reform are insincere in their aims. They just want to play politics, and dangerous, nationalist politics at that.

- 80 Iskhakov (2001).

59Negative reactions to Tatarstan’s latinization campaign are not confined to the Russian press. In December 2000, the Russian Duma passed an anti-latinization measure. The measure stated that Tatarstan’s adoption of a Latin script was a threat to Russian national security and banned other constituents of the Russian Federation (such as Bashkortostan, where 24% of the population is ethnic Tatar) from using Latin script to print Tatar.80 Banning the use of Latin script among Tatars living outside of Tatarstan creates a difficult situation for Tatarstan nation-builders. Since only 1.5 million of Russia’s seven million Tatars live in Tatarstan, part of nation-builders’ vision includes promoting Tatar language and culture for Tatars residing beyond Tatarstan’s borders. Consequently, proceeding with alphabet reform within Tatarstan could sever communication between Tatarstan Tatars and external Tatars.

- 81 RFE/RL Tatar-Bashkir Service, 29 May 2002.

60Despite opposition, the Tatarstan government doggedly persisted in its efforts to latinize: beginning with the 2000–2001 school year, sixty schools began to teach Perfected Yangalif to their pupils. Tatarstan’s Ministry of Education reported that students had no difficulty in mastering Tatar’s Latin script and they “demonstrated a growing interest in their [Tatar] lessons in general.”81 The Ministry of Education’s goal was to effect complete latinization of Tatar over the course of the next ten years.

61In 2000, before the Latin alphabet was adopted, several Tatar teachers I knew who were working in Kazan schools expressed opposition to it. For example, one teacher, Hayat apa, worried that Latin would impede children’s acquisition of Tatar because it would add an additional step to the learning process. However, after she began teaching the new script, she reported that her fears had been unfounded. A second teacher, who worked at Kazan’s Jewish School, told me that she considered the re-introduction of Latin script a project devised by the enemies of Tatar language. She was concerned that changing Tatar’s alphabet would render yet another generation of Tatars illiterate and further complicate her efforts to arouse interest in Tatar language among her pupils. The young teacher’s concern emerged from her personal experience of the written communication barrier that existed between herself, as someone literate in Tatar in Cyrillic, and her grandmother, who had been schooled in Latin in the 1920s.

- 82 September 11, 2001 was the date Islamic terrorists destroyed the twin towers of the World Trade Ce (...)

62After 9/11, members of Russia’s government began to frame their objection to Tatar’s Latin script as an Islamic threat.82 For example, in March 2002 Russian Duma Deputy Sergei Shashurin was quoted in a Radio Liberty Daily Review from Tatarstan as having said the following:

- 83 RFE/RL Daily Review, 13 March 2002.

“Trying to switch the Tatar language to Latin is the same thing as riding donkeys in Afghanistan”...the switchover would “threaten Russia’s national security and integrity via Turkish expansion.” [S]cript reform would lead Tatarstan to “what we have now in Afghanistan, thanks to the Taliban.”83

63Spinning the alphabet debate as a threat to Russian national security has successfully shifted its emphasis from one in which opponents treat linguistic pluralism as superfluous to a much more alarming anti-Muslim stance. Some Tatar intellectuals told me in private that they find this re-framing of the orthographic debate reminiscent of Stalinist-period paranoia about the enemy within, which resulted in millions of Soviets losing their lives. In the Russian-language mass media, in interviews with me, and in everyday conversations, many Tatar-speakers attempted to assuage the fears of those who object to latinization by professing that their cultural integration into Russian linguistic space is too total to be dismantled by the simple act of writing their native language in a different alphabet. To no avail.

- 84 Devlet (2009) notes that the law banning Latin script inadvertently affected Karelians.

64Beginning in spring 2002 a heated debate arose in the Russian Duma about an amendment to the federal law on languages that would prevent languages spoken in Russia from being written in anything other than the Russian alphabet. As a Tatarstan nation-builder and Russian Duma Deputy Fändäs Safiullin accurately pointed out, this measure would in effect outlaw the six additional letters created for Cyrillic Tatar subsequent to 1939.84 The slippage in Duma discussions between mention of “Russian” script and the eventual adoption of a law about Cyrillic provides insight into Russian imperialist attitudes towards non-Russian ethnic minorities. It exposes an underlying assumption that Russian language and Russian script should suffice for communication.

- 85 The text of the law can be read at http://wbase.duma.gov.ni/ntc/vdoc.asp7kN11635.

65On December 12, 2002, Putin signed a law prohibiting the writing of Russian’s languages in any script not based on Cyrillic.85 The law, which required Tatarstan to desist from teaching Tatar in Latin by December 2003, incited outrage from some Tatar quarters. However, just as Tatarstan people adopt various positions towards other political questions, not all Tatars necessarily support latinitsa.

- 86 RFE/RL Tatar-Bashkir Service, 10 December 2002.

66Three stories Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty published in December 2002 about attitudes towards the new law among Tatars living in Bashkortostan illustrate this. In one, Supreme Mufti of Russia Talgat Tajetdin, who is stationed in Bashkortostan’s capital Ufa, called upon Putin to sign the Cyrillic-only law, stating that “changing the language’s script in one of Russia’s entities would irreparably harm the entire Tatar national culture, the community of the country’s peoples, and would cause distrust and alienation in their relations.” As the Tatarstan newspaper Vremya novostei pointed out, Tajetdin was trying to curry favor with Putin by representing himself as less radical than other Muslims, such as those on Tatarstan’s Muslim Religious Board, which favors latinization.86

67In addition, a group of people claiming to represent Bashkortostan’s Tatars sent a collective letter to Putin in which they wrote:

- 87 Ibid.

Changing our writing will result in separating the entire Tatar people, including those living in Tatarstan, from Russian culture and its invaluable heritage. Apart from this, much money will be spent on new textbooks, developing methods of teaching, translation of books, training teachers, and finally, changing street signs.87

68Similar to Fazlullin’s objections in 1938 to adapting Russian’s Cyrillic alphabet to accommodate Tatar phonology, these post-Soviet period writers invoke the logistical difficulties of introducing Perfected Yangalif.

69However, since the Russian economy is now subject to market forces, reference to logistics is framed in terms of financial expense, instead of as complications in factory production.

70Six days after these two stories appeared, another Bashkortostan Tatar, likewise claiming to represent his community, contradicted both Tajetdin’s statements and those made in the collective letter. Elfir Sakaev, Deputy Chairman of Bashkortostan’s Tatar National-Cultural Autonomy, stated that:

- 88 RFE/RL Tatar-Bashkir Service, 16 December 2002.

[His organization] was indignant about the Russian media’s campaign against Tatar-stan’s transition to a Latin-based script and was surprised by the recent message from Telget [sic] Tajetdin to Russian President Putin...Only Tatars, and not some Muslim leaders or Russian politicians, should decide on how to express their native language.88

71These published controversies over the reintroduction of a Latin alphabet for Tatar have successfully projected significant rifts between Tatars and Russians and among different groups of Tatars, regardless of whether or not those rifts exist outside the sphere of mass media. The controversies demonstrate the extent to which opinions which profess to be about alphabets in fact concern wholly different matters. During a period of political instability not experienced in Russia since the 1920s, how the minority nationalities choose to write their national languages has assumed great significance. This is because ethnic Russians perceive writing in latinitsa as a rejection of the idea of a Russian state in which ethnic Russians maintain cultural and political hegemony. And, indeed, it is.

Conclusions

72In this chapter I have traced the ways in which Soviet languages and nations became ordered in a hierarchy of cultural evolutionary stages of development and how this hierarchy eventually caused an alphabet to become outlawed. Studying language codification in the USSR demonstrates the negotiation inherent in creating standardized systems of linguistic notation and indicates how these systems become deeply politicized in state societies.

- 89 The Russia-based journal Ab Imperio does publish research that addresses these commonalities. Howe (...)

- 90 Europe and the People Without History is a seminal work by anthropologist Eric Wolf that describes (...)

73Standardization was one of several quite successful means for creating discrete nationalities out of Russian Muslims. These effects are evident from the ways post-Soviet Turkic intellectuals express a desire to maintain their national uniqueness by retaining the features particular to their national alphabets. The increasing russification of minority languages during the Soviet state-building period—most pointedly, the speedy movement from descriptions of their particularities to prescriptive measures to make them more like Russian—is part of a colonial policy, which many Tatar intellectuals perceive as a continuation of Russian imperialist aspirations dating back to the 16th century. What they don’t perceive as colonialism, by and large, is how Soviet policies fragmented knowledge about minority peoples. Thus, while former Soviets are familiar with the sanctioned (and generally superficial) information about each other once transmitted via official channels, they don’t tend to think comparatively about Soviet rule, often perceiving what they suffered as the sole such occurrence. While foreign scholars are beginning to piece together inclusive views of Soviet nationalities policies and their effects, the results of this research have not been shared with its subjects and so, inter alia, former Soviets remain largely ignorant of the commonalities in their lived experiences.89 At least as salient an effect upon minority nationalities is how alphabet changes make impossible acquiring familiarity with texts created in previous writing systems and render even highly literate nations, such as Tatars, people without history, and therefore more prone to social atomization and easier to control.90

74The alphabets government linguists created for Tatar language in the 1920s-1930s at first implicitly and then explicitly adopted Russian language as the standard against which Tatar was measured. Russian likewise became the standard for the vast majority of Soviet minority languages. It remains the standard against which people in Russia define the Tatar language in the early 21st century.

75At least three competing attitudes towards the re-introduction of a Latin alphabet for Tatar language have emerged since the early 1990s. For some Tatar nation-builders the recreation of a common Latin script symbolizes an end to colonial isolation through the rejection of a writing system decreed by fiat. Ending Tatars’ isolation entails movement towards other Turkic-speaking people, including the Turks of Turkey, and facilitating their entry into the world of globalized computer communications. Other nation-builders see in the creation of a common Latin alphabet the loss of the Tatar nation’s uniqueness, which signifies a notable shift from their predecessors’ attitudes in the 1920s. How Tatars in other regions and Russian-identified people—whether they are Tatars who speak Russian exclusively or ethnic Russians—perceive latinization likewise varies. However, many of them consider Tatar’s Latin alphabet a treacherous act of rejection and a threat to Russian national security.

76How did these profound divisions in how Russian citizens perceive the world come into being? In the next chapter I begin to answer this question by describing in depth the cultural perspective from which Tatar-speakers have come to view the world in the post-Soviet period.

Note

1 See Jaffe (1996) and Schieffelin (1998) for similar analyses of the political implications of alphabets, in Corsica and Haiti, respectively.

2 Advancing national minorities was part of a policy called nativization, which Martin (2001) calls “affirmative action.” See also Hirsch (2005). For more on the relation between nativization and language planning, see Smith (1993) and (1998), who argues that the pendulum shift from nativization to russification wasn’t as dramatic as it is frequently depicted. My evidence for Tatar does not support this argument, rather fitting better with the positions taken by Kreindler (1982, 1985, 1989), Lewis (1972), and Silver (1974a).

3 After 1932 policies more frequently structured the practice of ethnography than the other way around (Slezkine 1994b). Lewis Henry Morgan was a 19th-century American cultural anthropologist specializing in Iroquois Indians, who proposed—like other evolutionists of the period—that cultures advanced through universal evolutionary stages from savagery through barbarism to civilization. Savagery is roughly equated with economies organized around hunting and gathering, barbarism with sedentary populations usually practicing some food production and living in villages, while civilization implies the existence of cities. Marx and Engels were enamored of Morgan, and Engels incorporated Morgan’s theories in his 1884 book, Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State.

4 Lenin (1914); Martin (2001).

5 Kirkwood (1989); Kreindler (1989); Lewis (1972). Beyond all of its inaccurate essentialist presumptions, this approach leaves no room for the children of mixed marriages, as they are called in the Soviet context.

6 Chikobaeva (1950: 15); Slezkine (1994b: 250–252). Marr’s method emerges from earlier theories of cultural evolution that treat human development teleologically.

7 See, for example, Austin (1992) on Karelian and Faller (2000) on Tatar.

8 The chart is adapted from Yakovlev (1926: 36–37).

9 Yakovlev’s presumption is contraindicated by the fact that at the turn of the 21st century when half (approximately 5,000) of the world’s languages are in danger of extinction, over half the world’s population is nonetheless bilingual.

10 Morgan’s purported stages of development (savagery—barbarism—civilization) easily became conflated into non-urban (i.e., backwards) and urban (i.e., modern). Perceiving the differences between urban and rural as absolute is not unique to Soviet state-building. See Williams (1973) for example.

11 Schamiloglu (2001) views the Soviet Union as a continuation of the Russian Empire insofar as central government policies oppressed non-Russian peoples.

12 Published the following year under the title Marxism and Linguistics in the United States.

13 Ibid.

14 Stalin (1950a: 76).

15 For example Chikobaeva (1950: 12) writes about Marrism thus, “Vocal speech, according to N. Ya. Marr, originated not for purposes of communication (people spoke with their hands!), but as a “labor-magic” activity [50–500 thousand years ago]; there are only four primary words or elements; they were in the possession of medicine men, and even these used them not as a means of communication with people...but...with a totem... It turns out that vocal speech, the property of medicine men, originated in a class-differentiated environment...as an instrument of class struggle.”

16 For Stalin a language—as opposed to a class dialect—has its own basic lexical fund and grammar, and exists under the economic conditions necessary for evolution into an independent national language, the speakers of which therefore have the potential to evolve into nations (Stalin 1950c: 96).

17 Stalin (1950a: 74).

18 Ibid., 71.

19 Stalin (1950c: 97; 1950a: 75).

20 Stalin (1950c: 98).

21 Kreindler (1989: 53, 56).

22 See Artiunov (1978), for an example of the former and Grant (1983) and Lewis (1972) as examples of the latter.

23 Kreindler (1989).

24 Maksimov (1990: 64).

25 Maksimov’s implies that Tatar semantic fields have become less narrow due to Russian influence, for the first “calques” cited by Maksimov are in fact terminological trappings of Soviet propaganda—bourgeoisie, proletariat, soviet, Party, and democracy, while the second ones include true calques from Russian, for example üzeshçenlek (self-work orientedness) for samodejatel’nost’(self-activeness; viz. independent activity). Moreover, the Tatar word collocations he lists as representing the evolution of semantic fields also indicate an apparent accommodation of Soviet concepts, such as syjnfyj köräsh from politicheskaja bor’ba [political struggle]. Maksimov’s argument here is misleading in a number of ways: in the above case he mistranslates syjnfyj [class or stratum] as politicheskaja [political]; in three examples his collocations are grammatically incorrect in that modified nouns are not appropriately affixed; and two of his examples employ Ottoman adjectival forms—syjnfyi and ädäbi [literary]—not associated with modernized Turkic dialects. The use of Ottoman forms may or may not mean that the broadening of semantic fields Maksimov describes predates Sovieticization, but it does sow a seed of skepticism regarding whether these calques are recent inventions.

26 For example, Maksimov wants to introduce the Russian word politik to replace the already existing sayasat, which was borrowed from Arabic prior to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

27 Sagdeeva (1990: 127).

28 Sagdeeva objects to the following sentence on the grounds that it suffers from “interference” from Russian, “Bu kyz bik kul’turaly kienä,” meaning “This girl is very culturedly dressed.” Sagdeeva underlines the word kul’turaly to indicate that it represents interference from Russian (Ibid., p. 128). Kul’turaly is composed of the Russian word kul’tura and the Turkic suffix [ly], which creates adjectives or adverbs, and here approximates the Russian word “kul’turno.”

29 See my article, Faller (2000), for a more detailed description of prescriptive grammars in the early 1990s. As Bilaniuk (2005) points out, ideologies of linguistic purism, such as the one espoused by Sagdeeva, are a common characteristic of asymmetrical language contact situations, and not particular to the post-Soviet context.

30 Lenin (1970). This shift was likewise supported by most Turkic intellectuals in the service of the Soviet system (Lewin 1994; Slezkine 1994b), who were all jadids (modernizers). See Smith (1998) for more on Lenin’s attitude towards latinization, as well as a more detailed discussion of the various aspects of the alphabet debates.

31 Turkic-speakers who did not convert to Islam, for example, Tuvans and Yakuts, never adopted an Arabic writing system.

32 In anthropology, the study of societies emerged historically in England, while the study of cultures was initially an American tradition. Marx, Engels, and their intellectual offspring based their evolutionary schema on the American ethnologist Lewis Henry Morgan, as noted above. Thus, even though much of the evolution discussed in this chapter pertains to the social, I will use the term “cultural” throughout.

33 No scholar thus far has analyzed Soviet orthographic reforms to present the big picture of alphabet reform and its effects.

34 Zhirkov (1926: 20).

35 Pavlovich (1926).

36 This orthographic ideology also governed the adoption of a Latin script in the Republic of Turkey around the same time. See Lewis (1999).

37 Zhirkov (1926: 21). Heartfelt thanks to my dear friend Maksim Kolopotin for his most insightful exegesis of what Byzantine politics means. He explained it “means simply corruption, patriarchy, intrigues, cruelty, cunning, protectionism—everything typical of medieval Byzantine Empire and its heir, the Russian Monarchy (the self-proclaimed Third Rome), esp. in XVI-XVII centuries.”

38 Kurbatov (1999).

39 Evidence of dissent comes from one contributor to the government-sanctioned volume, The Battle for a New Turkic Alphabet. Broydo, Deputy Director of the Commissariat for Nationalities in the early 1920s, attempted to refute the commonly asserted ideology equating writing with political, economic, and belief systems. Broydo expresses his opinion concisely, “And no matter how much Chechen children are taught Latin script, not a single one of them, under that [single] circumstance, comes closer to European culture and her literary treasures...” (1926: 40). Furthermore, Broydo discounts claims that Arabic is inherently more difficult to learn than Latin, asserting that difficulties in acquiring Arabic script could be obviated by improving teaching methods.

40 Lenin (1970).

41 Pavlovich (1926).

42 Zhirkov (1926).

43 Agamaly-Ogly (1926: 14); Ibrahimov in Kurbatov (1999).

44 Broydo (1926); Crisp (1989).

45 During the following school year, 1927–28, a latinized Tatar began to be taught in technical and secondary schools. In 1928–29, Latin was introduced into schools at all levels.

46 Kurbatov (1999).

47 See Smith (1993) for more on the split between linguists who supported the phonetic over the phonological principle. Polivanov was also a famous Orientalist in his own right and a prominent member of the Prague School of Linguists, who died in 1938. For more on the Prague School, see Steiner (1982) and Vacheck (2003).

48 Slezkine (1994a).

49 My observation is that the [ž] allophone sometimes, but not necessarily, indicates a more emphatic “no.”

50 In other words, it possesses phonemic significance.

51 Schafer (1995).

52 For more on the concept of verbal hygiene, see Cameron’s (1995) book by that name.

53 Native speakers do adhere to front-back oppositions in speech, even though their metalinguistic terminology for describing vowel harmony models itself on Russian’s grammatical system.

54 Kurbatov (1999: 97).

55 Alpatov (1991).

56 Research by American sociolinguist William Labov (1966) on how lower middle class people try to adopt upper class linguistic features, in which he traced the source of larger linguistic changes to changes in the speech patterns of individual speakers, provides an example of how linguists generally conceive of languages.

57 Other research on Soviet minority languages demonstrates that this was the general attitude during this period (Austin 1992); (King 1999); (Lemon 1991, 2002).