Contemporary Art Collectors: The Unsung Influences ont the Art Scenes

| , ,Contemporary Art Collectors: The Unsung Influences on the Art Scene

Collectionneurs d’art contemporain : des acteurs méconnus de la vie artistique

Texte intégral

Collectors on the Contemporary Scene, Profiles and Patterns

Graduates, Senior Citizens and Île de Paris Residents

1According to this survey, (see Aspects of Methodology, page 18) the current art collecting population is largely male (73%) with a higher-than-average level of education, with three quarters of collectors having completed the equivalent of 4 years of higher education (i.e. ≈ master’s degree) (Figure 1). Just over one quarter of collectors (27%) are art history graduates.

Figure 1 – Breakdown of collectors by level of educational qualification

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

2Around two thirds of collectors (64%) are aged over 50 and around half of them (47%) (Figure 2) are resident in the Île-de-France area. This profile matches that of arts patrons generally. There is indeed a strong correlation between higher education graduates and museum and gallery attendance, the latter also attracting higher proportions of residents of urban areas. Moreover, the higher average age of collectors is partly explained by lifestyle-related financial resources: the purchasing of artworks requires a certain budget, which effectively excludes a large section of the young population.

Figure 2 – Breakdown of collectors by age

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Differing Routes into Collecting

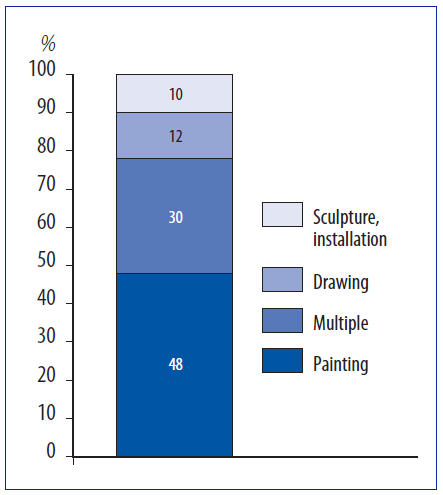

3All collectors remember the first work they acquired, but the age at which this first acquisition is made varies: for 43% of them it was between the ages of 20 and 30 and one third starting their collection even earlier than that. For around half of collectors, the first work they acquired was a painting, one third chose a print, engraving or lithograph with only 10% acquiring a drawing (Figure 3). Family environment also plays a determining role: one third of collectors knew a collector within their family, and 8% had parents working in the art sector, jobs which only account for 2% of the working population.

Figure 3 – Type of work first owned by collectors

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Figure 4 – Proportion of leisure time spent on collecting

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

4Creating a collection requires an investment not just of money but also time and energy: it involves information gathering, visits to exhibitions, engagement in the artistic scene by keeping up-to-date with the latest exhibitions etc. One third of collectors spend the majority of their free time on collecting, with 9% spending all of their free time doing so (Figure 4). Only a small percentage of those interviewed (7%) spend part of this time on creating or updating a collection-related website.

Varying Sizes and Types of Collection

5From the smallest collections, i.e. those comprising less than 50 items, which represent one third of our sample group, to the largest, which contain over 200 items, (one in 5 collections) there is a huge variation in the size of collections contemporary artists, a very large proportion of the works owned were made after 1945 (68%). Most collections are not specialist (66%) and for three quarters of them, the majority are by French artists or artists resident in France. One in 10 collections comprises exclusively French artists.

Figure 5 – Collection size by number of items owned

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

6Painting is the most popular medium, featuring in almost all collections (90% of cases), with three quarters containing sculpture, photography and drawing; around half of collections feature artists’ books, whilst videos and installations feature less commonly (Figure 6).

7NB: 90% of collections contain paintings, 74% contain sculpture, etc.

8Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Varying Financial Commitments

9The average investment budget varies considerably (Figure 7), with 30% of collectors spending less than 5,000 euros each year on artworks, whilst at the other end of the scale, some 16% spend over 50,000 euros.

10Relative to their annual income, three quarters of collectors spend the equivalent of one month’s income per annum on their acquisitions, and one quarter spend more than the equivalent of 2 months’ income (Figure 8).

Figure 8 – Proportion of average annual income spent on purchasing work(s)

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

11The maximum amount spent on one work shows just how diverse collector profiles are: one quarter of them have never spent more than 5,000 euros on a single work, whilst one in ten has already spent over 100,000 euros on a single work (Figure 9).

Figure 9 – Maximum amount spent purchasing a single work

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

The Extent of Collector Involvement in Artistic Life

12Collectors of contemporary art are not merely buyers. They operate on both sides of the market, not only creating demand, but also supply through their involvement in artistic life. Thus, over three quarters of collectors act in a variety of different ways to support those involved in the art ecosystem: the collector may invest in production (orders, financing of catalogues, etc.), dissemination (loans for exhibitions, presenting to other collectors, etc.), or assistance (financial, material or other support). Collectors’ actions may involve various other parties, e.g. artists, galleries or indeed institutions.

Involvement with Artists: Assistance, Support for Production and Dissemination

13Collectors’ involvement with artists can take different forms, such as assistance and support with production or dissemination. Over half of collectors (54%) claim to be involved in at least one of these forms of support of artistic creation (Table 1).

Assistance

14One third of collectors provide material or financial support to artists. Material support generally involves making available premises such as studios or accommodation, or supplying materials. Financial support may take the form of gifts, loans or advances from collectors to help out struggling artists. This help sometimes takes the form of a gift/payment in kind or gift/purchase when the artist gives their patron one of their works in return for their support. The regular purchase of works from an artist is another practice aimed mainly at providing the artist with an intermittent income; works acquired in this way may not always be quite those the collector might have chosen if free of this obligation.

15A few more original examples of financial support were revealed in the course of interviews with collectors, such as raising funds from groups of friends: in return for this assistance, which enabled the artist to produce works of art for exhibitions, contributors received original drawings. These various forms of assistance are not mutually exclusive and several different types may be provided concurrently; moral support may also be given alongside material and financial assistance, for example.

Supporting Production

16Commissions are another form of collector commitment and 44% of them say they have made them to artists. Of course, some of these commissions cover traditional transaction scenarios, as occur for example when acquiring a personalised work such as a portrait. However they can also be the expression of a desire to give support, for example when the work commissioned is then the subject of a particular exhibition. Such support is generally motivated mainly by cultural considerations, the actual act of purchasing not being the ultimate aim. 32% of collectors claim to have been involved in financing the production of a work for the purpose of exhibiting it in galleries or institutions.

Supporting Distribution

17In addition to material or financial assistance (through loans or support for production), certain collector activities can help establish an artist’s reputation and/or bring to light new talent, for example working in conjunction with exhibition organisers. 35% of collectors claim to have collaborated on an exhibition project with an exhibition organiser or critic and 33% claim to have published or helped finance catalogues for artists whose work they collect. The variety of ways in which collectors might get involved in exhibition projects emerged over the course of the interviews. It may include the creation, hiring or financing of premises, the loan of their own apartment or even collaboration with institutions. In some cases the collectors themselves may take on the role of exhibition organiser.

Table 1 – Collector Behaviour Defined by Different Forms of Artist Support

|

As a % |

Visits to artist studios |

View advice of collected artists as |

Size of collection by number of works owned |

Free time devoted to collecting |

Purchase directly from artist |

|||||||||

|

Yes |

No |

important |

not important |

< 100 |

> 100 |

Most |

Some |

A little |

Often |

Sometimes |

Never |

|||

|

Assistance |

||||||||||||||

|

Material assistance |

74 |

26 |

62 |

38 |

78 |

22 |

32 |

52 |

16 |

23 |

49 |

28 |

||

|

No |

67 |

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

33 |

88 |

12 |

79 |

21 |

45 |

55 |

48 |

43 |

9 |

43 |

49 |

8 |

|

|

Financial assistance |

77 |

23 |

67 |

33 |

69 |

31 |

36 |

50 |

14 |

27 |

51 |

23 |

||

|

No |

67 |

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

33 |

90 |

10 |

79 |

21 |

43 |

57 |

48 |

44 |

8 |

47 |

46 |

7 |

|

|

Support for Production |

||||||||||||||

|

Help supporting |

77 |

23 |

65 |

35 |

72 |

28 |

35 |

51 |

14 |

30 |

49 |

21 |

||

|

No |

68 |

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

32 |

89 |

11 |

83 |

17 |

36 |

64 |

51 |

42 |

8 |

41 |

50 |

10 |

|

|

Support for Distribution |

||||||||||||||

|

Assistance with project of exhibition |

74 |

26 |

65 |

35 |

76 |

29 |

32 |

54 |

15 |

26 |

59 |

22 |

||

|

No |

65 |

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

35 |

96 |

5 |

81 |

19 |

41 |

56 |

54 |

37 |

9 |

46 |

46 |

9 |

|

|

Financing a Catalogue |

75 |

25 |

65 |

35 |

73 |

27 |

36 |

51 |

13 |

28 |

50 |

21 |

||

|

No |

67 |

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

33 |

94 |

7 |

83 |

17 |

35 |

65 |

49 |

40 |

11 |

44 |

47 |

9 |

|

NB: 33% of collectors provide material support to artists; of them, 88% visit artists’studios, 79% view the advice of the artists they collect as important, 55% have a collection exceeding 100 pieces, 48% spend most of their free time on their collection and 43% regularly purchase direct from the artist.

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

18Collector involvement may also be symbolic, by sharing their social capital with artists for example. By opening up their networks to them, they expand the artist’s potential market, (through contact with other collectors) and may help improve their artistic credentials (through introductions to gallery owners and institutions etc.). In some cases, artists may get the benefit of the collector’s professional network, for example when their works have been used to form a corporate collection designed to introduce company employees and partners to artworks. Help with distribution can also take more unconventional forms, when collectors take on the role of artist management or by helping them with administrative or financial matters, looking for sales or exhibition premises or even helping them with their accounting. This support may also take the form of help with communications: drafting press releases about artists’ collections or financing advertising campaigns.

Collectors and Artists: A Necessary Encounter?

19Almost three quarters of collectors meet the artists whose work they collect; for one in five collectors this is standard practice. There are a number of motivating factors behind wanting to get to know the artist: the desire for a dialogue and to understand the works and the artistic process. The relationship also helps to validate the choices they make. Conversely, for other collectors, all that matters is the work of art itself, transcending the artist entirely.

20As such, the artist’s personality, financial relationships or indeed the fact that the work eclipses the artist may attenuate this desire for a connection with the artist. Equally, the relationship may also deteriorate over time, as the collector feels trapped and obliged to buy a work because of their relationship with the artist. Certain collectors wondered about the nature of the artist’s involvement in such a relationship, fearing that their interest in them was motivated more by financial and material concerns than a straightforward desire for friendship.

21Collectors committed to certain artists are more likely than others to visit artists’ studios, to heed advice given them by artists and to go directly to them for their artwork purchases (Table 1). For example, 46% of collectors who have taken part in organising an exhibition claim to purchase directly from the artist on a regular basis, as compared with just 26% of those who have not taken part in such projects. Similarly, 96% of them have visited artists’ studios and 81% view artists’ advice as important, as compared with 74% and 65% respectively for other collectors.

22Collectors committed to certain artists spend a considerable amount of time on their collection: almost half of those who claim to give material assistance to an artist also spend the greater part of their free time on their collection, whereas this figure is closer to a third (32%) for those who do not provide financial support.

23We also see a financial or material correlation between financial investment in the form of catalogue financing and size of collection. Two thirds of collectors (65%) who have financed a catalogue possess over 100 works of art, whereas only a quarter (27%) of those who have never been involved in this kind of financing fit into this ownership category.

24Nevertheless, although they are more likely to view artists’ opinions as important if they provide them with financial support (61% compared with 47%), those who get involved in producing works and catalogue financing seem more independent in their decision-making and show very specific motives. A small proportion view the advice of exhibition organisers and gallery owners as important.

25Whether it entails help with production, involvement in an exhibition project or catalogue financing, around 6 out of 10 collectors taking part in this kind of activities claim to view them as important, as compared with the 4 in 10 who have not engaged in this kind of support.

Involvement with Museums

26Through their relationships with institutions such as museums, collectors are able to provide artists with rather more considerable support.

27Museum Membership Schemes, Loaning of Works, Sitting on Acquisitions Committees, etc.

28One of the most common forms of involvement is by becoming a supporting member (or “friend”) of a museum: 60% of collectors provide this kind of support (Table 2). Such supporter schemes give them access to services and privileges such as studio tours, private views, etc. in return for their financial support of the institution.

29Over half of collectors lend works to museums. 27% have made these loans in France alone, 29% in France and abroad. Only 2% of collectors make loans on an exclusively international basis.

30Finally, there are more specific forms of involvement which often require a closer relationship with an institution: sitting on an institution’s administrative or acquisitions committee (14%), or even donations (8%) or long-term loans of works (8%) to a museum. The law governing a number of these practices no doubt has some bearing on the more exclusive relationship this activity entails, which moreover necessitates a close collaboration between the institution and the collector (see the section “Legal Framework for Donations and Long-Term Loans of Works to Museums”, below).Moreover, there is a positive correlation between the fact of having acquired one’s first artwork at an early age (before the age of 20) and making donations and long-term loans (46% of collectors), and loans in France and abroad (42%) whilst this has no impact on administrative involvement with museums (being a member of an administrative committee or membership support scheme).

Legal Framework for Donations and Long-term Loans of Works to Museums

31In addition to provisions designed to encourage the expansion of public collections after collectors are deceased (donation procedures and fiscal measures for legacies) various measures also exist to cover collectors during their lifetime (Heritage Code) with regard to donations and long-term loans made to museums in France.

32For a work from a private collection to be placed in museum, prior consultation is required with the Commission Scientifique des Musées Nationaux. A contract is then drawn up setting out conditions of the long-term loan to which is appended a description of the work’s condition. A long-term loan of this nature may not be shorter than 5 years. It is possible to extend it through an amendment to the contract. The contract may also stipulate conditions under which its owner may withdraw the work for a limited period with the prior agreement of the depository. Obviously, such long-term loans are made free of charge.

33The donation of works to a museum either as a gift from hand to hand or through an officially recorded procedure, may confer certain tax benefits. A sum equivalent to 66% of the value of the donation (the value of the work having been evaluated by an expert) may be deducted from income tax, up to a value of 20% of taxable income. Where donations exceed 20% of the collector’s taxable income, any remaining balance may be carried over for the next five years. Moreover, in accordance with Article 1131 of the General Tax Code, any gift from hand to hand to the state is exempt from capital transfer tax. It should also be noted that the donor may attach various clauses to this gift and stipulate presentation and conservation conditions for the work. Specifically, where donations are made on a usufruct basis, the donor retains the right to enjoyment of the work for a contractually predetermined period.

Variations in Behaviour According to Collector Involvement

34Compared with other collectors, those involved with institutions spend more of their free time on their passion. There is a positive correlation between higher involvement levels and larger collection sizes, particularly those among those making loans in France and abroad (63% of those who lend works have collections which exceed 100 items). Their budget is therefore considerable: 30% of collectors who make donations or long-term or short-term loans have a budget in excess of 50,000 euros, as compared with 6% of those do not engage in this kind of activity.

35Whatever the nature of their relationship with institutions, the more involved collectors tend to make more visits to foreign exhibitions than those with no involvement. This statistical disparity may be twice as large again for collectors who are supporting members of a museum.

36External advice from exhibition organisers is considered important by those collectors who sit on administrative or acquisitions committees and those collectors who are supporting members of a museum (73% and 61% respectively) as well as those who make donations or long-term loans (63%). The latter category form a distinct group in that they are more likely to exclusively hold work produced post-1945 (57%), tend not to collect anything other than art (56%) and own mostly only work by French artists or those resident in France (65%).

Collectors and Institutions: A Game of Attraction and Frustration

37Most collectors say that their passion was initially sparked by a museum or exhibition visit in their youth. Many also cite the importance of encounters with curators during their artistic education. However, their relationships with institutions are complex. On the one hand, when they see their choices confirmed by a museum they see it as both validation and a recognition of their own involvement, whether they be asked to sit on an administrative or acquisitions committee, or indeed loan one of their works On the other hand they often bemoan institutions’ lack of recognition for their support, particularly in the case of short-term loans of their works. Institutions abroad are generally better regarded from this point of view, although nine out of ten collectors believe that these short-term loans were generally made under good conditions in France.

38Furthermore, several collectors have expressed dismay that they are often reduced to the role of mere service providers or regarded simply as a source of funding rather than being fully acknowledged as partners or providers of additional expertise alongside institution members. Collectors are seen as patrons without the legitimacy of curators.

Table 2 – Collector Behaviour Defined by Different Levels of Involvement with Institutions

|

As a % |

Visits to fairs abroad |

Size of collection |

Free time spent on collection |

Average budget devoted to collection |

||||||||||

|

Regularly |

Rarely |

Never |

< 100 |

> 100 |

Most |

Some |

A little |

< 10,000 |

Between 10 |

> 50,000 |

||||

|

Supporting member of a museum |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

30 |

39 |

17 |

44 |

73 |

27 |

31 |

47 |

22 |

67 |

25 |

8 |

||

|

Yes |

60 |

75 |

11 |

14 |

53 |

47 |

46 |

48 |

6 |

38 |

39 |

20 |

||

|

Member of an administrative or acquisitions board at a contemporary art museum or institution |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

86 |

56 |

15 |

29 |

64 |

36 |

37 |

49 |

14 |

65 |

30 |

16 |

||

|

Yes |

14 |

87 |

7 |

7 |

41 |

59 |

52 |

43 |

5 |

20 |

63 |

16 |

||

|

Loan of works to institutions for an exhibition |

||||||||||||||

|

France |

27 |

89 |

5 |

6 |

57 |

43 |

42 |

42 |

15 |

42 |

42 |

14 |

||

|

France and abroad |

31 |

96 |

3 |

1 |

37 |

63 |

57 |

36 |

7 |

22 |

47 |

31 |

||

|

None |

42 |

79 |

11 |

14 |

80 |

19 |

25 |

60 |

15 |

74 |

20 |

6 |

||

|

Gift or long-term loan of a work to a museum |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

92 |

58 |

15 |

29 |

36 |

50 |

14 |

56 |

3 |

12 |

||||

|

Yes |

8 |

76 |

8 |

16 |

52 |

41 |

7 |

28 |

42 |

31 |

||||

NB: 60% of collectors are supporting members of a museum; of them, 75% regularly go to fairs abroad, as compared with 39% of collectors who are not supporting members. 46% spend the majority of their spare time on their collection and 20% have a budget of over 50,000 euros for their art collection.

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Involvement with Galleries

39Most collectors follow the work of just a few galleries (39% keep up with fewer than five galleries or exhibition spaces, 32% between five and ten), either because they have built up a special relationship with a few gallery owners, or because they don’t have time to keep up with more. As a result of this close relationship, the collector may sometimes end up helping out a struggling gallery with some financial support. This support can take two forms: the first is the equivalent of a kind of savings investment plan, with the collector paying a monthly amount to the gallery owner in exchange for one or more works; in the second, more common scenario, the collector buys works on a one-off basis.

40The collector’s involvement may also include participation in gallery activity; either occasionally, by financing a catalogue for example, or more systematically and specifically in instances such as joint gallery owner/collector initiatives, whereby the gallery owner comes up with the artists and ideas whilst the collector provides the funding for the project. Collaborations may also be intellectual in nature, with the collector proposing ideas or playing an active role in gallery activities.

Collectors and Gallery Owners: A Love/Hate Relationship

41Gallery owners enjoy the favour of most collectors. Galleries are their main supply source, with only 6% of collectors claiming never to buy works from galleries (see Figure 10).

42For many collectors, galleries are the place where they learnt to develop their tastes. 74% of collectors consider advice from gallery owners to be either important or very important (see Figure 11).

43Certain collectors revealed in interviews that they could sometimes go against their initial instincts and follow the recommendation of a gallery owner in whom they trust. Others highlighted how relationships of trust and friendship had been built up over time with a number of gallery owners.

44However any indebtedness which collectors may feel towards certain gallery owners does not preclude them from taking a sometimes very critical view of the financial nature of this relationship. Generally speaking, the profession is seen as rather closed and unfriendly.

Figure 10 – The frequentation of purchase places

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Figure 11 – Advice Sources Considered Important When Making a Purchase

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Concomitant Forms of Involvement

45Collectors’ involvement in supporting the arts scene is usually manifold. The seven most commonly cited forms of involvement are: the loan of a work for an exhibition at an institution; material or financial support for the artist; serving on a contemporary art institution’s administrative or acquisitions committee; organising an exhibition in collaboration with an exhibition organiser or critic; publishing or financing artists’ catalogues; donation of works to a museum; long-term loan of works to a museum. Four out of five collectors engage in at least one of these activities. Of them, many engage in several activities: almost 40% of collectors are involved in at least three different activities (Figure 12).

Figure 12 – Number of Arts-Scene-Related Activities

NB: 20% of collectors are not involved in any kind of activity. 21% are involved in one activity, 20% are involved in two activities, etc..

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

46The relationships they form with the institution depend on how closely involved they are. Loans and support for the artist are the main forms of involvement (Figure 13). The more activities collectors are involved in, the more diverse and institutionally-orientated governing donations and long-term loans submitted for acceptance by expert committees partly explain the low incidence of these practices.

Figure 13 – Nature of involvement when individuals only engage in one particular activity

NB: where collectors claim to be involved in just one type of activity, 47% of them do so by means of the loan of a work and 21% through financial support for the artist. The remaining 32% includes the five other forms of involvement.

Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Different Forms of Involvement with Varying Motives

47Collectors investing in the art scene are motivated by four main factors. Whilst there may be altruistic motives behind their involvement, they are also guided by personal motives (such as the pursuit of cultural and aesthetic pleasure), social motives (a desire for status or acceptance within a particular social group) or indeed financial motives (to make money or to acquire cultural assets). These motives are not mutually exclusive, and their predominance and intensity vary with each collector.

Altruistic Involvement

48Collectors’ involvement in artistic life may, primarily, be down to altruistic motives. In such cases, collectors derive satisfaction not by improving their own individual situation through consumption or production, but from the well-being of others. Certain collectors thus claim to feel a sense of social responsibility, supporting artists and galleries not for personal gain but to help them with their career and/or to provide them with a little more security. Such assistance is often provided at critical moments, when their artistic activity is under threat.

49Altruism may for example take the form of paying over the odds for an artist’s work. Young artists, for example, who are inexperienced in this market may offer prices which are either too high in relation to their reputation, or too low for them to cover their costs and make a living. Some collectors may, in this situation, willingly offer young artists a higher price than that initially demanded. This altruistic gesture may be prompted by aesthetic, family or friendly concern.

Aesthetic and Cultural Issues

50A collector’s motivation may derive from the fact that they derive personal satisfaction from collecting. While dealing with works themselves gives collectors a direct sense of enjoying their artistic and aesthetic qualities, their involvement in artistic life more generally opens them up to what might be termed its associated pleasures, those which enable them on the one hand to refine their taste and, on the other hand, to enjoy the satisfaction of contributing to “emerging” art.

51Sociologists and economists have emphasised the role which experience and training can play in forming taste. A collector’s involvement may, in part, result from their desire to form their taste. Meeting artists in their own homes or in dedicated workshops gives them a better understanding of the artistic process. Similarly, meeting professionals such as critics, curators or exhibition organisers, and sharing their views and analyses of works, helps them to hone their own opinions. More generally, being involved in an institution’s governing body or even organising exhibitions can help them to understand the processes behind producing and valuing contemporary art and the unwritten rules of the art world. Collectors may, moreover, derive satisfaction from the support that they give to the creation of art and the role they play in the creative process.

52Moreover, collectors may become involved in the arts scene because they view it as a kind of public good. In this particular instance, it is not so much possessing the work which is important as the fact that purchasing it helps support artistic creation. Their actions allow them to be a part of the contemporary art scene in all its diversity, sometimes in response to what are seen as the rather too “safe” choices made by institutions, and it is this very vitality which gives them satisfaction.

53Finally, through their involvement in the art scene, collectors learn by doing, deriving particular pleasure in being a part of the creative process and contributing to the diversity of creation.

Social and Status Issues

54A third possible motivating factor behind collectors’ involvement in the art scene is its social aspect: the satisfaction derived from their involvement comes more from the fact of connecting with others, and the social status and related benefits they confer. Their involvement is partly related to the satisfaction they get from mixing with people in an environment which is seen as valuable, interesting and stimulating. Collector associations and museum supporter groups play an important role in bringing together collectors themselves or bringing together collectors and institutions. Their involvement may also be connected to a desire for status, which is conferred in two ways. Firstly, through the fact that their tastes differ from the rest of the population; so, it is not unusual for the aesthetic pleasure derived from the appreciation of a work to be enhanced by a feeling of pride on the part of the collector in being part of an enlightened minority which has access the work, and the fact that they were among the first to recognise the importance of the artist, setting them apart from the rest of the population.

55This desire to stand out is one of the driving factors that help keep the art scene so vibrant: their pleasure in an artist’s works diminishes as they become more widely known, so collectors naturally turn towards promoting lesser-known artists.

56On a more mundane level, the ostentatious display of one’s collection or related assets is another way of getting a name for oneself.

57Generally speaking, some collectors, particularly those in provincial areas, derive genuine satisfaction from appearing to be movers and shakers on the local art scene and from being recognised as such.

Economic Issues

58Ultimately it would be naive to assume that collectors’ involvement in artistic life is entirely divorced from economic and financial concerns. Firstly, their involvement with institutions in particular gives them access to privileged information on promising artists, which is all the more precious given that most collectors, even the wealthiest, claim to be unable to follow the spiralling prices which drive the current art market.

59Secondly, their involvement means that from their position they can put about information which may affect the prices an artist can command, particularly those in their own collections. Indeed, it is often joked that the minute François Pinault stops to look at a painting in an exhibition, the artist’s market value immediately skyrockets. Of course, very few collectors are in the enviable situation of conferring legitimacy upon works of art in this way, but simply being on an institution’s acquisitions committee brings a great deal of influence. It is entirely legitimate for a collector to use their institutional position to promote the artists that they like and invest in, so long as they can persuade the other members of the committee that their choices are appropriate. Similarly, loaning a work for a popular exhibition can only improve the subsequent value of the work.

Categorising Collectors: From the Semi-professional to the Independent

60In addition to being situated somewhere along a scale which runs from unalloyed action to more institutionally-focused action, the extent to which collectors’ involvement affects the art scene is linked to certain variables Collection size is in this regard a good indicator: those not involved in production activities tend to have collections of fewer than 50 works, whilst involvement in production is correlated to collection size, and tends to be more institutionally-focused as collection size increases. Analysis of various connections has revealed four main collector types, classified according to their particular form of involvement.

Semi-professional Collectors1

- 1 The typical characteristics of collectors within this category should be seen in relation to the ot (...)

61This first group involves collectors who are highly involved in recognised production-related activities. They are already involved in running projects with institutions, have made long-term and short-term loans to museums, finance catalogues and assist with production. At the same time, they loan their works both in France and abroad.

62They act in a quasi-professional capacity, claim to spend all of their free time on their collection and generally began collecting before the age of 20. They trust their own judgement and are little influenced by the fact that a work may have previously been exhibited in a gallery or other respected place. Consequently, they claim not to follow the work of galleries in particular. Moreover, decoration is not a motivating factor for them. They make their purchases from a number of different places. They regularly make purchases from artists and auctions and fairly frequently from other collectors

63The collection size and the purchasing power of this group are quite considerable: the maximum sum spent on the work may be in excess of 100,000 euros and with collections sometimes exceeding 200 items.

Committed Collectors

64Collectors in this category are also involved in production -related activities, but in a rather different way to the semi-professional collector group. They are often asked to sit on the administrative committees of various different institutions or to lend works from their collections both in France and abroad. They generally acquire their first work in their early adult life, between the ages of 20 and 30. They spend the majority of their free time on their collection, are very active in seeking out information, they read Art Press, attend the Basel art fair and regularly keep up with the activity of between 5 and 10 galleries, often more. They promote the artist’s work and acknowledge that they are influenced by the fact that works which appeal to them have been exhibited in a gallery or in another respected location. They are also influenced by critical opinion.

65These collectors generally go through the usual market channels. Although they claim to regularly make their purchases through galleries, they also attend art fairs and may sometimes buy at auction. On the other hand, they never buy works online.

66Their collections contain between 100 and 200 works, and highest price they will have paid for a work varies between 10,000 and 50,000 euros.

Level-headed Collectors

67Level-headed collectors are much less involved in production-related activities than the semi-professional or committed collector, yet they do maintain some involvement. Although they do not invest in exhibition catalogue production and tend not to sit on institutional administrative committees, they still make loans to French institutions. These collectors begin collecting as they enter adulthood, between the ages of 20 and 30, and claim to divide their spare time equally between collecting and other hobbies.

68Like the committed collectors, they refer to a number of different sources to validate their views on a work and regularly keep up with the work of several galleries, generally fewer than five. For them, the fact that a work has been exhibited in a place or a gallery which they respect is an important choice criterion. Moreover, the fact of a work being available at auction may also have an influence in some cases. Unlike the committed investor, decorative considerations very often motivate their purchases. They rely on fairly common acquisition sources: sometimes galleries, rarely directly from artists and never from other collectors.

69Their collections are on average slightly smaller than those of the previous two categories and include fewer than 50 works, acquired for a maximum price of between 10,000 and 50,000 euros.

Independent Collectors

70These collectors tend to have begun collecting after the age of 30, are not involved in production -related activities and do not loan their works. They only spend a small amount of their free time on collecting, spend little time researching information and do not follow any galleries in particular, although they may on the other hand attend local art fairs. They are fairly independent in their judgement, attaching little or no importance to the fact that a work may have previously been exhibited in places or galleries which they respect and they claim not to be swayed by critical opinion. Acquisitions are motivated by the choice of a particular work rather than by the artist’s overall approach.

71The networks on which they rely to purchase works are innovative: although they do not necessarily spurn galleries, the internet tends to be a favoured acquisition channel, whilst they tend not to attend auctions at all.

72They generally have a collection of fewer than 50 works and they will not have paid more than 5,000 euros for any one work.

Conclusion

73These four collector profiles simply offer a snapshot of collectors’ investment in artistic life at the time the survey was conducted. In reality, these investment levels are not set in stone and may change over the course of a collector’s “career”. Within each group, whether the semi-professionals, the committed, the level-headed or the independents, there will be individuals whose profile covers a broad spectrum spanning two following extreme positions.

74On the one hand, there are those whose involvement in artistic life springs from an overwhelming desire to maintain and enhance their collection. In such cases, involvement can be seen more as a means than an end in itself, its aim is to help build the collection. Through the information that this involvement provides, and the network they build up, collectors improve their capacity to find a work which fits their collection. These collectors often take a straightforward approach to the market: they buy and sell using various of the available channels (artists, galleries, collectors, auction houses). In loaning their work and by helping with catalogue publication, they thereby help improve the profile of the artists whose work they own. In doing so, these very actions actually help invigorate the art scene.

75At the other end of the spectrum are those collectors whose involvement is motivated by a desire to get closer to the process of artistic creation. Ownership of a collection is simply the consequence of their desire to support emerging artists; in this situation, what counts is their relationship with those involved in artistic creation.

Annexes

Methodological Overview

In the absence of national statistics on collector activities, it is hard to build up a clear statistical picture of the contemporary-art-collecting community, and thus it is hard to categorise.

For the purposes of this research, any individual who regularly purchases works of art is considered as a collector, this avoids creating bias in the research by defining a priori what a “good collector2” might be.

“Contemporary art” is defined as any work produced by a living artist. This survey is problematic in that collection is essentially a private activity: consequently there is no source which gives a precise idea of the size and profile of the parent population of collectors of work produced by living artists.

To build up an idea of this population and create a suitably varied sample, particularly with regard to collection size and time spent by collectors on their hobby, the survey questionnaire was widely distributed throughout various networks: museum membership support schemes in both Paris and the provinces, regional institutional networks (DRAC, FRAC, fine arts schools, etc), galleries and individual intermediaries. The questionnaire was strictly anonymous and available online in a PDF format, for submission via email (stipulating that the anonymity of all respondents would be respected) or via post.

The questionnaire and the interview format were organised around 6 main themes: the origin of the collector’s collection, information and choices, the defining features of their collection, management of their collection, the collector and the art scene and finally individual profiles. Qualitative, semi-directive interviews were then conducted with the relevant target groups. The main challenge was to find a wide range of profiles, in addition to the more media-savvy collectors.

The survey was conducted between January and June 2014.

332 responses were collected, and the collector profile was similar to those characteristics which emerged from AXA’s international survey of 900 art collectors, conducted in 2013 (Collecting in the Digital Age, AXA Art Insurance, 2014).

66 semi-directive interviews were conducted with collectors, each averaging an hour and 30 minutes. Ten of these collectors were suggested by the Association pour la Diffusion Internationale de l’Art Français (ADIAF), the rest were contacted on the basis of recommendations by gallery owners or the heads of regional or national contemporary art-based institutions. Other individuals also came forward having filled out the questionnaire or when contacted by researchers on the basis of their own individual research or recommendations from other collectors.

44 interviews were conducted in provincial France, 22 in the Île de France region; they included 47 men, 8 women and 11 couples (Tables A and B).

Table A – Breakdown of interviewees by age (semi-qualitative interviews)

Source: SAC D/DEPS. French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Table B – Breakdown of interviewees by profession (semi-qualitative interviews)

Source: SACD/DEPS. French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015

Notes

1 The typical characteristics of collectors within this category should be seen in relation to the other categories. Therefore, phrases such as “they loan their works both in France and abroad”, this should be understood to mean, they do so more frequently than collectors in the other categories.

2 In academic literature, there are two different ways of defining a collector. The first takes a non-utilitarian, quantitative approach, and determines that one becomes a collector “when one has run out of walls for one’s works” (i.e. “one becomes a collector when one no longer views a work as a decorative object”). The second takes a more qualitative approach, emphasising the importance of the selection process: “The collector is guided by a certain taste”.

Table des illustrations

| |

|---|---|

| Titre | Figure 2 – Breakdown of collectors by age |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-1.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 33k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 3 – Type of work first owned by collectors |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-2.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 22k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 4 – Proportion of leisure time spent on collecting |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-3.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 19k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 5 – Collection size by number of items owned |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-4.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 22k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 6 – Type of Work Collected |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-5.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 40k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 7 – Average annual budget |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-6.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 27k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 8 – Proportion of average annual income spent on purchasing work(s) |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-7.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 24k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 9 – Maximum amount spent purchasing a single work |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-8.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 24k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 10 – The frequentation of purchase places |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-9.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 39k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 11 – Advice Sources Considered Important When Making a Purchase |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-10.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 31k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 12 – Number of Arts-Scene-Related Activities |

| Légende | NB: 20% of collectors are not involved in any kind of activity. 21% are involved in one activity, 20% are involved in two activities, etc.. |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-11.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 11k |

| |

| Titre | Figure 13 – Nature of involvement when individuals only engage in one particular activity |

| Légende | NB: where collectors claim to be involved in just one type of activity, 47% of them do so by means of the loan of a work and 21% through financial support for the artist. The remaining 32% includes the five other forms of involvement. |

| Crédits | Source: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, 2015 |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-12.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 13k |

| |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-13.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 22k |

| |

| URL | http://books.openedition.org/deps/docannexe/image/935/img-14.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 40k |

Le texte seul est utilisable sous licence CC BY-NC 4.0. Les autres éléments (illustrations, fichiers annexes importés) sont « Tous droits réservés », sauf mention contraire.